DUBAI: Among the artefacts on show in the “Roads of Arabia” exhibition, on show for the final weekend at Louvre Abu Dhabi, is a photograph of a handsome young man.

He is an imposing figure, with chiseled features and his eyes hinting at a shrewd intelligence. His is the face of a man accustomed to command, a man who might change history — as indeed he did.

Abdul Aziz bin Abdul Rahman bin Faisal bin Turki bin Abdullah bin Mohammed Al-Saud was such a man. Known more commonly as Ibn Saud, he became the founding father and first monarch of the country which bears his name: the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

The photograph was taken in Kuwait in 1910, when he was about 35, and is among the first pictures taken of the future king, for he had never seen a camera before. The man who arranged the sitting — and in all likelihood took the photograph — was only the second European Ibn Saud had encountered. But Captain William Shakespear, a British explorer and diplomat, became such a trusted friend that the Arab leader called him “brother” and made him his military advisor.

The photograph was taken in Kuwait in 1910, when he was about 35, and is among the first pictures taken of the future king, for he had never seen a camera before. The man who arranged the sitting — and in all likelihood took the photograph — was only the second European Ibn Saud had encountered. But Captain William Shakespear, a British explorer and diplomat, became such a trusted friend that the Arab leader called him “brother” and made him his military advisor.

And it was thanks — certainly in part — to their closeness that Britain and Saudi Arabia signed a treaty to formalize a friendship that endures to this day.

William Henry Irvine Shakespear was a son of Empire. Born in Bombay in British India in 1878, he served as an officer in the Bengal Lancers before joining the British Foreign Office in 1904 and five years later was posted to Kuwait as a political agent.

He was not a typical colonial official. A gifted linguist, he spoke Urdu, Pashto, Farsi and Arabic, and indulged his passion for photography, botany and exploration with long expeditions into territory that had never been mapped, where he met and talked with Bedu tribesmen and studied the flora and fauna of the desert.

Shakespear soon formed the view that the man to watch was Ibn Saud, son of the emir of Najd and scion of a proud ruling tribe. He was physically imposing — well over six feet tall and a proven warrior who, after a decade in exile, had recaptured Riyadh, the Al-Saud power base from the rival Al-Rashid tribe.

The chance to meet Ibn Saud came one day in February 1910 as Shakespear returned from a journey into the eastern desert. The trip had gone drastically wrong when tribesmen overran the camp, shot dead his chief guide and almost killed Shakespear himself. But then they recognized the rest of his party as old acquaintances and joined them around the campfire for gahwa (Arabic coffee) and storytelling.

On returning to Kuwait, Shakespear found an invitation from the ruler, Sheikh Mubarak Al-Sabah, to a banquet in honor of his visitor, Ibn Saud.

It was a most lavish affair which “cannot have cost less than £20,000 ($25,600),” Shakespear noted in his report.

In his diary he recorded that Ibn Saud was “a fair, handsome man, considerably above average Arab height with a particularly frank and open face and, after initial reserve, of genial and very courteous manner.”

The two men, who were roughly the same age, hit it off straight away and Shakespear invited Ibn Saud to dine at the British diplomatic residence the following evening. Over a classic British meal of roast lamb with mint sauce, roast potatoes and tinned asparagus, the Arab nobleman was impressed not only by his host’s fluency in Arabic but by the way he could converse knowledgeably about aspects of desert life, including hunting with falcons and saluki hounds.

It was, as authors David Holden and Richard John wrote in their book “The House of Saud,” “a cordial meeting of minds” that deepened over many lengthy conversations in Riyadh and in remote desert camps.

Britain was keen to extend its influence over the Gulf, and Shakespear urged his masters to recruit Ibn Saud as an ally. But London hesitated. Kuwait was controlled by the Ottoman Turks, who in turn were Britain’s “buffer” against other, more hostile European nations trying to carve up the region, and Turkey was allied with the Al-Rashids, enemies of the Al-Saud. Even when Ibn Saud drove an Ottoman garrison out of the coastal oasis of Al-Hasa, Britain still would not commit, to Shakespear’s immense frustration.

However, as he was coming to the end of his stint as a political agent, London consented to his request to visit Riyadh on his way back home.

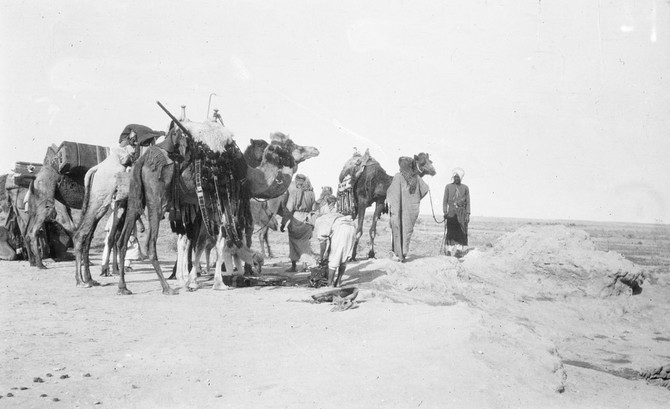

After five weeks on the back of a camel, he arrived to a warm welcome from his friend. It was during this stay that Shakespear took photographs of Ibn Saud and local scenes that comprise the first pictorial record of the Arabian heartland, showing Riyadh as little more than a village with mud walls, although, as Shakespear noted: “Quite a third of the town is taken up by the homes of the Saudi family.”

The outbreak of World War I changed everything. Turkey sided with Germany. Suddenly, the British were desperate to have Ibn Saud as an ally against Turkey and dispatched Shakespear back to Riyadh to keep him away from the Turks at all costs.

Within a week of his arrival in January 1915, Shakespear had drafted the first Anglo-Saudi document, which recognised Ibn Saud as independent ruler of Najd under British protection and sent it off to Kuwait for approval.

Meanwhile, Ibn Saud rode 400 kilometers north with 6,000 men to confront the forces of his old enemy, the Al-Rashids, at a spot called Jarrab in what was both a traditional bedouin battle, with camels and plenty of hand-to-hand combat, and a proxy war between Britain’s newly signed-up ally and the Turkish-backed Al-Rashids. Shakespear made the fateful decision to tag along to photograph the event.

On Jan. 24, scouts reported that Al-Rashid forces were mustering nearby. Ibn Saud urged Shakespear to stay behind at Qassim, but the Englishman wouldn’t hear of it. Riding in on a camel, wearing his British khaki uniform and pith helmet, he set up his camera in the center of the Saudi line on a hilltop. When the Al-Rashids charged, he made an easy target.

At the end of the battle, Shakespear lay dead, but nobody was sure how he had died until his personal cook, Khalid bin Bilal, provided a first-hand account. Bilal had been captured in battle but escaped two days later and overheard Al-Rashid fighters talking about the Englishman who had been killed.

Bilal went to the elevated spot where he had last seen his master carrying his camera and found his body, which bore three bullet wounds. A digitized form of his account was released by the British Library in 2015, a century later.

Shakespear was 37 when he was killed. His diaries, notes and photographs went to the Royal Geographical Society, but historians have speculated on what other diplomatic successes he might have achieved and how different both Gulf and British history might have been had he lived.

What is known is that on Dec. 26, 1915, Britain and Ibn Saud signed the first Anglo-Saudi Treaty — the document drafted by Shakespear — and that the great Saudi leader never forgot his English friend.

Many years later, when he was king of Saudi Arabia, he was asked who he considered to be the greatest European he had met. Without hesitating, he replied: “Captain Shakespear.”