Major Robert Grenville Gayer-Anderson has given his name to one of the most enjoyable cultural outings in Cairo, a visit to the Bait Al-Kretliya, which consists of two beautifully restored old Islamic houses joined together by a bridge, popularly known as the Gayer-Anderson Museum.

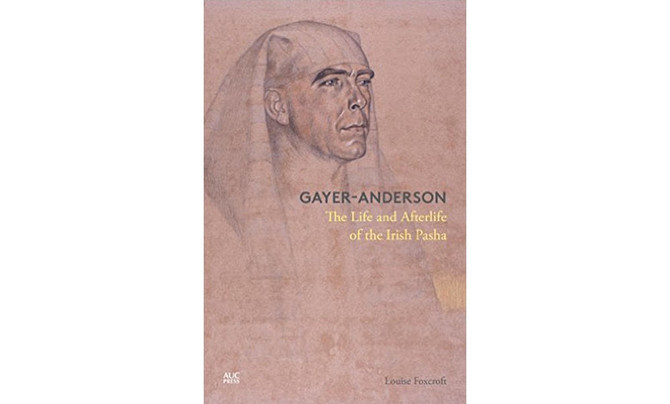

For the first time a biography, “Gayer-Anderson: The Life and Afterlife of the Irish Pasha” explores the fascinating life of a man who was a colonial government representative and also received the title of Pasha by King Farouk. Known also as John, and P.U.M. (a mysterious acronymic nickname that his identical twin brother Thomas gave him), Robert Grenville Gayer-Anderson studied to be a surgeon, but he was also a soldier, an adventurer, an enthusiastic collector of antiquities and a passionate Egyptologist. In this intimate portrait of a multifaceted and enigmatic figure Louise Foxcroft attempts to reveal the person behind the persona.

Gayer-Anderson is mostly remembered for acquiring a most remarkable collection of antiquities, mostly from ancient Egypt. He had always expressed his wish to visit an empty tomb. This rare privilege finally took place in 1923, a year marked by an extraordinary event, the discovery of Tutankhamun’s Tomb by Howard Carter. Gayer-Anderson was at the time posted in Egypt as assistant Oriental secretary. He was, therefore, a member of the official party invited at the private opening of the tomb of Tutankhamun.

When Gayer-Anderson entered the tomb, he immediately noticed the charming models of ships, baby chairs and chariots. The following day, he mentioned in a letter that he believed Tutankhamun was a youth about 17 or 18 years old. An X-ray examination proved that he was right: Tutankhamun was just under the age of 18 when he died. At the end of the visit, Gayer-Anderson decided that he had not seen enough and he made up his mind to return for another visit to the tomb with his mother.

Gayer-Anderson was very close to his mother, Mary. In an unpublished memoir, “Fateful Attractions,” on which this book is based, Gayer-Anderson acknowledges that he inherited from her a profound love of beauty, which he compared to the “bread of life.” His father, Henri Anderson had a violent and cruel nature. He submitted his child to a Spartan upbringing, which was deeply resented by young Pum and his siblings. Placed in a row in front of their father, the children were subjected to painful things. “He would give a sudden shout, quickly raise a threatening hand, tickle our ribs, pinch us or pull our hair… in spite of which none of us must show the slightest emotion of any sort. If we flinched, flushed, giggled, gasped, laughed or even flickered an eyelid we were shouted at and slapped,” writes Gayer-Anderson.

Henri Anderson played these mean and nasty games during their last year in North America. During their harrowing stay, Henri Anderson managed to make some money in real estate and a very young Pum developed his passion for collecting. He found some lead bullets and chipped flint arrowheads.

During his life, Gayer-Anderson had the knack to find exceptional pieces. He has a remarkable flair for discovering precious antiquities. One of his first important finds was an unusual bone, which he discovered during a walk over the Medway after the family had returned to the United Kingdom. He showed it to his form-master who suggested that he send it to the Royal Geological Society. The bone was a humerus, which turned out to be part of an unknown type of pterodactyl, or “flying dragon.” This fossil was the first in a long list of gifts that Gayer-Anderson gave to museums.

Henri Anderson decided that his son should become a doctor like his two uncles. At the age of 17, he started training at Guy’s Hospital in London and qualified five years later as Member of the Royal College of Surgeons and Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians.

During that time, he also found a man’s portrait in oils on a broken panel that he bought for a shilling. With his usual flair, Gayer-Anderson had noticed the signature of Van Dyck at the back. It was later confirmed by experts as authentic. Gayer-Anderson had become more than ever addicted to collecting. “It became both a vice and a mania,” he wrote.

When he finished his medical studies, Gayer-Anderson was appointed assistant house surgeon to William Arbuthnot-Lane. He had been encouraged to aim for a Harley Street career but that was not the life he wished to lead. He was looking for something else, something more adventurous. He was just 23 years old, young and restless, so he decided to follow his twin brother and join the Royal Army Medical Corps. In 1907, he was posted to Egypt with the rank of major.

“Pum’s lifelong affair with Egypt, its culture, and its people had begun” writes Foxcroft.

On a trip to Khartoum where he was replacing a local surgeon who had been taken ill, Gayer-Anderson bought a beautiful bronze Horus from a wealthy dealer. In time, he realized that he should be more careful and buy only from “less known and less-knowing” dealers, men who knew little and lacked the expertise so that one could buy rare antiquities for very little money.

After two years, Gayer-Anderson returned home for a holiday. As he was sailing back to England, he realized how much he had changed. He was no longer interested in medicine, and he desperately wanted to return to Egypt. At the end of 1909, he was posted back to Egypt as inspector of recruiting for the Sa’id, the seven provinces of Upper Egypt.

As he traveled along the Nile several times a year, he got to know local traders who would run after him as soon as they spotted his boat. Gayer-Anderson was doing an astonishing amount of dealing and collecting. In fact, collecting became his main occupation to the detriment of his service ambitions. Egypt was a cradle of civilization and Cairo was a center for Middle Eastern and Far Eastern art including India, China and Persia. Gayer-Anderson was particularly fond of Fayoum. Fayoum is the largest oasis in Egypt and the closest to the Nile and Cairo. It has a host of archaeological sites from the Middle Kingdom when Fayoum was a center of political power. Gayer-Anderson wrote in his memoires that Fayoum was the “most exciting and fascinating place I know from a historical and antique-collecting point of view. Nowhere in the world can one see history and pre-history more abundantly and consecutively written.”

He could find in Fayoum a pre-dynastic vessel, an early dynasty stone-relief, Ptolemaic statues, Greek terracotta figurines or Roman glass bottles, the choice of objects was endless and the price was very low.

Gayer-Anderson was becoming an expert in ancient Egyptian and Saracen antiquities. “He bought from the shopkeepers or from the original finders, the sebakheen, who had an ancient and legal right dating from the days of the Turkish suzerainty to sift the sebakb, the dust and debris from a site. And from these families he got the rarest pieces for a fraction of their final value. In this way, he amassed large collections of all sorts. He sold some of them, making himself good money but he also bought for many of the larger museums in the United Kingdom, Sweden, and America,” writes Foxcroft.

Gayer-Anderson now in his early 30s had amassed a certain wealth and yearned to live the life that really pleased him. However, he would still have to wait a few more years. He had enjoyed “supreme happiness” during the first decade of the 20th century unaware that the world was “on the brink of a volcano.” During World War I, he was posted in Egypt and in Gallipoli on the Turkish coast. He ended his official career in Egypt with a post of senior inspector in the Ministry of Interior and was finally appointed Oriental secretary to the high commissioner where he remained for about a year. He retired from the Egyptian government in 1923. He was only 42 and he wanted to spend the rest of his life with his antiques and writing poems and articles for magazines.

In the 1930s, he was offered a job as director of the Anglo-American Nile Tourist Company, which gave him the possibility to continue searching for antiques. During that period he purchased one of his most precious pieces known as the Gayer-Anderson Cat, the first life-size bronze cat he had ever seen. He would eventually bequeath it to the British Museum. His last philanthropic action was the internal renovation of the Bait Al-Kretliya.

He was allowed to live in this old Islamic house during his lifetime in order to restore it. When he died, it was returned to the government as the “Gayer-Anderson Pasha Museum of Oriental Arts and Crafts.” The Bait Al-Kretliya has been magnificently restored. The Damascus room is stunning with its ceilings and walls covered in inlaid and gilded wood. A scene from a James Bond movie, “The Spy Who Loved Me,” was filmed in Bait Al-Kretliya. Gayer-Anderson also entertained many visitors including the King of Siam, Howard Carter and Freya Stark.

The eight years Gayer-Anderson spent at Bait Al-Kretliya were the happiest of his life. He would certainly be proud to see how his beloved home is one of the most visited museums in Cairo.

• life.style@arabnews.com

A journey from abused child to Egyptian antiquities collector

A journey from abused child to Egyptian antiquities collector

What We Are Reading Today: The Ghana Reader

Editors: Kwasi Konadu, Clifford C. Campbell

“The Ghana Reader” provides historical, political, and cultural perspectives on this iconic African nation.

Readers will encounter views of farmers, traders, the clergy, intellectuals, politicians, musicians, and foreign travelers about the country.

With sources including historical documents, poems, treaties, articles, and fiction, the book conveys the multiple and intersecting histories of the country’s development as a nation and its key contribution to the formation of the African diaspora, according to a review on goodreads.com.

What We Are Reading Today: ‘The Dream Hotel’

- “The Dream Hotel” is more than a compelling narrative; it is a reflection on the complexities of freedom and the influence of technology on our lives

Author: Laila Lalami

Reading Moroccan-American novelist Laila Lalami’s “The Dream Hotel” was an eye-opening experience that left me simultaneously captivated and unsettled.

The novel weaves a story about one woman’s fight for freedom in a near-future society where even dreams are under surveillance.

The narrative centers on Sara, who, upon returning to Los Angeles International Airport, is pulled aside by agents from the Risk Assessment Administration.

The chilling premise — that an algorithm has determined she is at risk of harming her husband — immediately drew me in. Lalami’s portrayal of Sara’s descent into a retention center, where she is held alongside other women labeled as “dreamers,” is both fascinating and disturbing.

What struck me most was how Lalami explores the seductive nature of technology. I found myself reflecting on our current relationship with data and surveillance.

The idea that our innermost thoughts could be monitored and judged felt unsettlingly familiar. As Sara navigates the oppressive rules of the facility, I felt a growing frustration at the injustice of her situation, which echoes broader societal concerns about privacy and autonomy.

Lalami’s writing is lyrical yet accessible, drawing readers into the emotional depth of each character. The interactions among the women in the retention center are especially poignant, showing how strength can emerge from solidarity.

As the story unfolds, I was reminded of the resilience of the human spirit, even under dehumanizing conditions. The arrival of a new resident adds a twist, pushing Sara toward a confrontation with the forces trying to control her. This development kept me invested in seeing how she would reclaim her agency.

“The Dream Hotel” is more than a compelling narrative; it is a reflection on the complexities of freedom and the influence of technology on our lives. It left me considering how much of ourselves we must guard to remain truly free.

In conclusion, Lalami has crafted a thoughtful and resonant novel that lingers after the final page. It is well worth reading for those interested in the intersections of identity, technology and human experience.

What We Are Reading Today: The River of Lost Footsteps by Thant Myint-U

Western governments and a growing activist community have been frustrated in their attempts to bring about a freer and more democratic Myanmar, only to see an apparent slide toward even harsher dictatorship.

In “The River of Lost Footsteps,” Thant Myint-U tells the story of modern Myanmar, in part through a telling of his own family’s history, in an interwoven narrative that is by turns lyrical, dramatic, and appalling.

The book is a distinctive contribution that makes Myanmar accessible and enthralling, according to a review on goodreads.com.

What We Are Reading Today: Return of the Junta by Oliver Slow

In 2021, Myanmar’s military grabbed power in a coup d’etat, ending a decade of reforms that were supposed to break the shackles of military rule in Myanmar.

Protests across the country were met with a brutal crackdown that shocked the world, but were a familiar response from an institution that has ruled the country with violence and terror for decades.

In this book, Oliver Slow explores the measures the military has used to keep hold of power, according to a review on goodreads.com.

What We Are Reading Today: Elusive Cures

- “Elusive Cures” sheds light on one of the most daunting challenges ever confronted by science while offering hope for revolutionary new treatments and cures for the brain

Author: Nicole C. Rust

Brain research has been accelerating rapidly in recent decades, but the translation of our many discoveries into treatments and cures for brain disorders has not happened as many expected. We do not have cures for the vast majority of brain illnesses, from Alzheimer’s to depression, and many medications we do have to treat the brain are derived from drugs produced in the 1950s—before we knew much about the brain at all. Tackling brain disorders is clearly one of the biggest challenges facing humanity today. What will it take to overcome it? Nicole Rust takes readers along on her personal journey to answer this question.

Drawing on her decades of experience on the front lines of neuroscience research, Rust reflects on how far we have come in our quest to unlock the secrets of the brain and what remains to be discovered.

“Elusive Cures” sheds light on one of the most daunting challenges ever confronted by science while offering hope for revolutionary new treatments and cures for the brain.