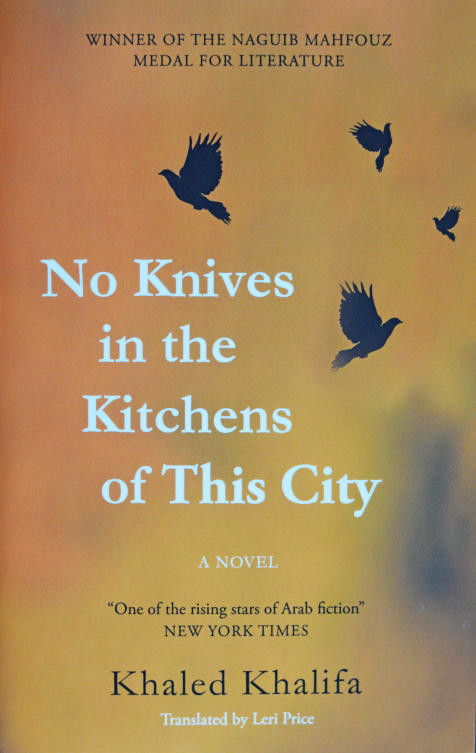

“No Knives in the Kitchens of This City” by Khaled Khalifa is a heartbreaking story of a Syrian family navigating Aleppo as politics, the president and loyalties ravage the city. Khalifa, who was born in Aleppo, is the author of four novels and the editor of the literary magazine Alif. He does not hold back in his descriptions of how Aleppo, from the 1960s to the 2000s, has fallen around families who have no choice but to live through the disasters. Translated into English by Leri Price in 2016, the novel won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature in 2013 and was shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2014.

Khalifa’s story is told and retold by his characters who long for the past when life was not as difficult. Following one family, the novel reveals the story of a mother who died “ten years too late,” according to her son. Her family must find their way through the streets of Aleppo amid its dwindling lettuce fields, overcrowded streets and loyal party members looking for allegiances and punishing those who do not praise the leader as they do.

Not a loyalist and marred by misfortune, the mother must make do with her life, even if her son’s birthday is marked by the Ba’athist coup of 1963, an event in history she despises which makes her feel as if “her life was a collection of mistakes that could never be resolved.” Her life deteriorates slowly after she, a dreamy woman with dark eyes, marries for love and eventually is left by her husband for another woman. She is abandoned by her own family, except for her brother known as Uncle Nazir, and forced to continue life as a school teacher with three children and her shame. But as her own life takes a turn down a twisted and unplanned path, so does Syria’s and its beloved city of Aleppo.

The regime’s takeover is swift — it forcefully grasps the country and its people. Neither their lives nor their surroundings are in their hands anymore.

From the narrator’s grandfather Jalal Al-Nabulsi, who is “proud of being from a family which had been in Aleppo for a thousand years,” one of the first employees of the Railway Institute and one of the only witnesses to the inception of the Syrian railway system, to a mother who “perpetually extolled the past and conjured it up with delight as a kind of revenge for her humble life,” to Sawsan who at first is irrepressible and then “immersed herself into radicalism and fatwas day after day,” Khalifa’s book weaves through the generations of the family.

His book depicts a fading picture, one that was once vibrant and full of life. He moves from Aleppo to Midan Akbas and back, through dusty roads and the Cinema Opera where childhoods were filled with Egyptian and Bollywood movies “with happy endings.” He tells the stories of women who leaf through trinkets and forgotten wares in the Bab Al-Nasr second-hand shop and bring them back to life to feel a semblance of magic. As “walking in the streets had become a terrifying experience” and violence and temperamental political attitudes take hold, his sentences and metaphors captivate the reader and will immerse you in Syria.

Time and age weigh heavily on the pages as a collapsing life and city add to the darkness that begins to take hold of Aleppo. Tales of love and dreams, of faded images that serve as motivation to move forward, are rampant. Mother manages to move on when she believes she is “divorced, not abandoned,” but for others, it is a little more difficult to convince themselves and find inspiration to move forward.

Khalifa’s book is reminiscent of Turkish novelist Sabahattin Ali’s style in the manner in which he hints that it is life that shapes people and not people who shape life. Like Ali, Khalifa’s story is about how circumstance decides the path one’s life will take. His love for the city and for Syria is ever-present in his every description and metaphor. He can enchant the reader with details of the city and its history, its buildings and the “rising fumes of death and the fear present in every street and on the face of every man and woman hurrying home in the early evening.”

But amid the fear are pockets of people who cling to music and passionate love, who attempt to keep hate away and defy the powers that be. Within the dark alleyways and molding walls, art, poetry and theater flourish. Sometimes, the characters live in their own momentary bubbles and are blind to the outside world in their pursuit of self-discovery and purpose. But ultimately, they are forced back to face the world and themselves.

In the darkness are bouts of light, but it is neither bright nor long-lasting and that is the truth and reality of Syria. Despite this, the resilience of Khalifa’s characters in their journeys is hopeful. This book paints horrifying pictures as beautifully as it does optimistic ones. Khalifa’s writing is whole, his sentences memorable, his characters strong and fearless. His strength lies in his ability to reveal harsh truths and ugly realities beautifully, to bring through the seas of hate, love and resilience.

In the end, when life hangs on by a thread, there is hope amid the pessimism as “Aleppo still embodied a dream of wealth and urbanity even though three-fourths of it had turned into slums unfit for human habitation.”

Book Review: A Syrian family stands tall as Aleppo falls

Book Review: A Syrian family stands tall as Aleppo falls

What We Are Reading Today: The Mechanics of Earthquakes and Faulting

- Focusing on brittle fracture and rock friction, this book will appeal to graduate and research scientists in seismology, physics, geology, geodesy and rock mechanics

Author: Christopher H. Scholz

A massive earthquake hit Myanmar and Thailand recently. Humanitarians are struggling to deliver assistance.

Why do earthquakes happen? “The Mechanics of Earthquakes and Faulting” offers a study on connections between fault and earthquake mechanics, including fault scaling laws, the nature of fault populations, and how these result from the processes of fault growth and interaction.

Focusing on brittle fracture and rock friction, this book will appeal to graduate and research scientists in seismology, physics, geology, geodesy and rock mechanics.

What We Are Reading Today: Thailand’s Political History

- Moving into the twentieth century, it traces the emergence of the Thai nation state, the large-scale investments in modern infrastructure

Author: B. J. Terwiel

“Thailand’s Political History” tackles some of Thailand’s most topical and pressing historical debates.

It discusses the development and evolution of the Siamese state from the early Sukhothai period through the fall of Ayutthaya to the rise of the Chakri dynasty in the late 18th century and its consolidation of power in the 19th.

Moving into the twentieth century, it traces the emergence of the Thai nation state, the large-scale investments in modern infrastructure.

What We Are Reading Today: ‘E.D.E.N. Southworth’s Hidden Hand’

- Southworth’s fiction tackled issues that were often considered taboo, including domestic violence, poverty and capital punishment

In her upcoming book, “E.D.E.N. Southworth’s Hidden Hand: The Untold Story of America’s Famous Forgotten Nineteenth-Century Author,” Rose Neal, who has a Ph.D. in English, revives the legacy of a now-obscure novelist who was once a household name.

Born in 1819, Emma Dorothy Eliza Nevitte, Southworth — better known by her initials, E.D.E.N. — was one of the most prolific and widely read American writers of the 19th century.

Christened with a long name, Southworth once joked: “When I was born, my family was too poor to give anything else, so they gave me all those names.”

She would later shorten it to the distinctive E.D.E.N., under which she built her literary empire.

With more novels to her name than Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, and Mark Twain combined, Southworth once captivated audiences with feisty heroines who rode horses, fired pistols, and even became sea captains.

Her most famous novel, “The Hidden Hand,” was so popular that readers named their daughters after its fearless protagonist, Capitola.

“Despite being one of the most beloved and well-known writers of the 19th century, as domestic sensational fiction declined in popularity, Southworth was entirely forgotten, as was an entire generation of women writers,” Neal writes. “For Southworth, it was partly because she had done so well at hiding her own progressive ideas. Nevertheless, she should be rediscovered and given her rightful place in American history.”

Southworth’s fiction tackled issues that were often considered taboo, including domestic violence, poverty and capital punishment.

Although she was raised in a slave-owning family, she wrote for The National Era, an abolitionist magazine, and encouraged her longtime friend Harriet Beecher Stowe to publish “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

She also supported the early women’s rights movement and advocated for better education and living conditions for those in poverty.

Neal’s journey to uncover Southworth’s story began unexpectedly as she pursued her master’s degree. She asked her colleagues whether they were familiar with this author she had unearthed. “They had never heard of Southworth or any of her novels,” she writes.

“How did a novelist as popular as Southworth slip into the dustbin of history?” she wonders.

With this biography, Neal pieces together Southworth’s story through her novels, letters and other documents, setting the record straight on a woman whose influence was far greater than history has acknowledged. Like her heroines, Southworth was bold, determined and ahead of her time.

The book comes out in May and is available for pre-order.

REVIEW: ‘Stories from Sol: The Gun-Dog’ offers a gritty, narrative-driven adventure

LONDON: In an era in which retro gaming is somewhat mainstream with remakes, reboots and remastered games emerging on a daily basis, “Stories from Sol: The Gun-Dog” on Nintendo Switch takes things to the next level.

Going further back in time than most, it is a throwback to classic PC-9800 visual novels, blending deep storytelling with a minimalist approach to gameplay. If you enjoy immersive narratives and do not mind slow pacing, this game delivers a compelling experience — though it may not be for everyone.

“Gun-Dog” is all about story. Its deep, character-driven narrative demands patience, rewarding players willing to engage with a text-heavy experience. It starts by setting the scene of the Solar War and our protagonist being unable to prevent the loss of his crewmates. Four years later, they (you can choose your own name) are re-assigned to the Jovian patrol ship Gun-Dog which has orders to investigate mysterious signals coming from the edge of Jovian Space.

On board, the assortment of characters includes a love interest, a rival from the past and others who all seem to be hiding something. While choice is limited to movement, item interaction and conversation, the game excels at making you feel like your actions matter, especially when decisions come with a countdown clock to force your hand.

This is not an action-packed adventure. The game moves deliberately and offers little in the way of fast-paced mechanics. Exploration is limited, but the weight of each choice — especially in high-pressure moments — keeps engagement high. With sparse visuals and bit-crushed music, “Gun-Dog” leans into its retro inspirations. Interestingly, putting it on mute might give the best experience; the soundtrack can be more of a distraction than an enhancement.

“Gun-Dog” is a game for those who love slow-burn, text-heavy adventures with minimal gameplay distractions. If you are looking for deep lore, strong characters and a narrative experience, it is worth the time. Just be ready for a slower ride than that offered by most modern games.

What We Are Reading Today: Moths of the World

- Moths of the World is an essential guide to this astonishing group of insects, highlighting their diversity, metamorphoses, marvelous caterpillars, and much more

Author: David Wagner

With more than 160,000 named species, moths are a familiar sight to most of us, flickering around lights, pollinating wildflowers about meadows and gardens, and as unwelcome visitors to our woolens.

They come in a variety of colors, from earthy greens and browns to gorgeous patterns of infinite variety, and range in size from enormous atlas moths to tiny leafmining moths.

Moths of the World is an essential guide to this astonishing group of insects, highlighting their diversity, metamorphoses, marvelous caterpillars, and much more.