MARRAKESH: The once teeming Jewish area of Moroccan tourist gem Marrakesh is seeing its fortunes revived as visitors including many from Israel flock to experience its unique culture and history.

“You’re now entering the last synagogue in the mellah,” the walled Jewish quarter in the heart of the ochre city, Isaac Ohayon says as he enthusiastically guides tourists in the courtyard of the Lazama synagogue.

“Many visitors come from Israel — you wouldn’t believe the demand!” adds the jovial 63-year-old hardware shop owner.

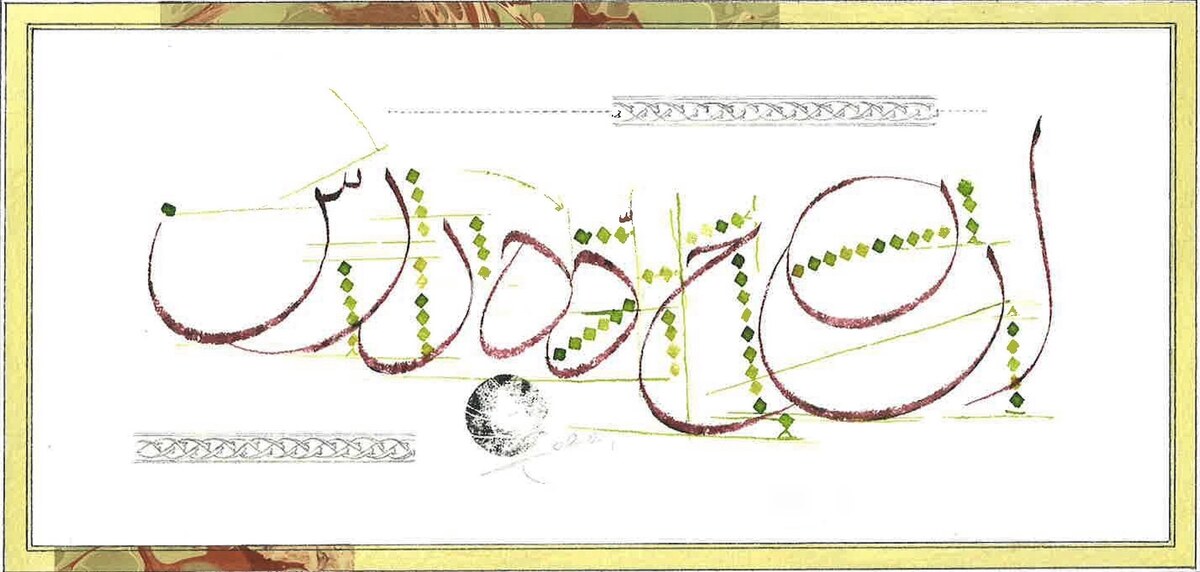

This place of worship and study was built originally in 1492 during the Inquisition when the Jews were driven out of Spain.

Known as the “synagogue of the exiles,” it hosted generations of young Berbers who converted to Judaism and were sent from villages in the region to learn the Torah, before finally being deserted in the 1960s.

In classrooms now transformed into a museum, fading color photographs tell the story of a now-dispersed community, with many having left for France, North America and especially Israel.

The caption on one sepia shot of an old man sitting by a pile of trunks says it all: “They are traveling toward a dream they have prayed for for more than 2,000 years.”

Rebecca is now in her fifties and grew up in Paris, but she has “great nostalgia” for Morocco and returns as often as she can.

“The Jewish Agency began recruiting the poorest in the 1950s and then everyone left after independence (from France), at the time of King Hassan II’s policy of Arabization,” she says.

The Jewish Agency of Israel is a semi-official organization that oversees immigration to the country.

Before the wave of departures, Morocco hosted North Africa’s largest Jewish community, estimated at between 250,000 and 300,000 people.

There are fewer than 3,000 left, according to unofficial figures.

Marrakesh at the foot of the Atlas mountain range was home to more than 50,000 Jews, according to a 1947 census.

Now, 70 years later, around 100 are thought to remain, many of them extremely elderly.

Jewish-owned homes inside the mellah were sold to Muslim families of modest means, and the walls of the district were eroded by time.

“Sometimes we can’t get even 10 men together for prayers,” says one woman worshipper at the old synagogue, preferring to remain anonymous.

But at celebrations marking the end of the festival of Sukkot, which commemorates the Jewish journey through the Sinai after their exodus from Egypt, and the Simchat Torah holiday, the place is buzzing with song, dance and traditional dishes.

The worshipper says she has “never seen so many people” there.

Jacob Assayag, 26, proudly calls himself “the last young Jew in Marrakesh.”

“Since the quarter was restored, there have been more and more tourists,” says the restaurateur and singer.

A restoration project begun just over two years ago has already seen 17.5 million euros ($20.5 million) spent.

Ferblantiers Square, a large pedestrian area near the spice souk lined with benches and palm trees where tourist buses gather, also benefited from the revamp.

Twenty years ago, the quarter was renamed “Salaam (’peace’ in Arabic),” but this year saw its original “El Mellah” name restored on the orders of King Mohamed VI “to preserve its historic memory” and develop tourism.

The streets with their ochre facades once more bear their names on plaques in Hebrew: the synagogue, for example, is on Talmud Torah Street.

There is much to see inside the mellah.

Camera-toting tourists snap vigorously at shopfronts and the carved wooden doorways of houses in the quarter.

“Many people come every year from Israel for the (Jewish) holidays, and this year has seen even more, maybe 50,000,” says Israeli tourist guide David, leading a group from Tel Aviv via Malaga in Spain on an eight-day trip.

“I feel at home in Morocco because I was born here,” adds the 56-year-old from the port of Ashdod just north of the Palestinian-controlled Gaza Strip.

His parents left Marrakesh in the 1960s, when David was just four years old, “because they were Zionists.”

Ohayon says visitors from the Jewish state are often bowled over by Marrakesh.

“Moroccan Jews can’t forget their homeland and Israelis who come here for the first time find the spirit of tolerance here almost unbelievable when they themselves live under constant tension,” he says.

Officially, Morocco has neither diplomatic nor economic ties with Israel, as this is a sensitive topic. Just two Arab states, Egypt and Jordan, have signed peace treaties with the Jewish state.

But in reality, there are few obstacles to both business and tourism.

Moroccan media reports say commercial exchanges between the two countries this year have amounted to more than four million dollars a month.

The kingdom, seen as a safe destination, recorded a more than 10 percent rise in tourist arrivals between January and August this year over 2016, with eight million visitors.