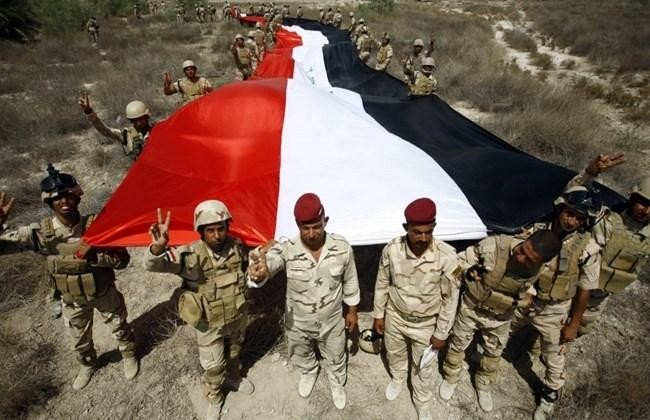

This year was a much better one for Iraqis, who have suffered severe security, economic and political conditions during the past three years after Daesh militants overran the northern and western parts of the country and seized almost a third of its territories, killing tens of thousands of people and displacing millions.

All this was accompanied by a quasi-bankrupt treasury and a drain on the country’s financial and human resources because of the war on the militants, but the situation is much improved and Iraq has finally come out of the “neck of the bottle,” according to analysts.

“It is certainly a year of achievements and an end to most of the crises that have strangled Iraq over the past years,” Abdulwahid Tuama, a political analyst told Arab News.

“Liberating the Iraqi territories, ending the war against Daesh, lifting the long-term economic sanctions imposed on Iraq, the rise in oil prices and the significant improvement of the Iraqi-regional relationship are all major breakthroughs achieved in 2017,” Tuama said.

Iraqi Prime Minister Haider Abadi on Dec. 9 declared the end of the three-year-long war against Daesh and the liberation of the Iraqi territories. A day earlier, the UN Security Council unanimously voted on Iraq’s exit from Chapter VII and ended 26 years of economic sanctions imposed on the country since Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1991.

The battle to liberate Mosul, the largest populated Iraqi city-seized by Daesh, was the fiercest, the biggest and the longest in the campaign waged by Iraqi forces and its backers against the radical organization.

More than 100 000 Iraqi troops, backed by US-led military coalition air forces and the Shiite-dominated Popular Mobilization troops, fought for almost nine months to regain control of the city, which included the most important and largest strongholds of the militants, the headquarters of control and command and the biggest weapons depots of the organization in Iraq.

By the end of the battle on Feb. 19, more than 25,000 militants had been killed, military officers said.

“The battle to retake Mosul is the most important one, because it broke the backbone of the organization and completely paralyzed it (Daesh) and ended its military capacity,” Retired Gen. Emad Allow, a EU adviser on terrorism, told Arab News.

“This battle also witnessed a significant development in the combat skills of the Iraqi security forces, as the fighting was fierce and house-to-house because of the nature of the city,” Allow said.

Baghdad has been immersed in its war against terrorism in recent years. This has encouraged the regional government of the Kurdish region, semi-autonomous since the 1970s, to extend its control over the disputed areas which lie outside the 2003-constitutionally approved part of the region.

The northern oil hub city of Kirkuk and its lucrative oil fields are at the core of the disputed areas between Baghdad and Kurdistan since 2003. The Kurdistan regional government held a controversial referendum on independence in late September.

“Holding the referendum (on independence) was like an earthquake that hit the political process in Iraq. It was no less a force in its impact than the (2014) fall of the three provinces into the hands of Daesh,” political analyst Joma’ah Al-A’atoani told Arab News.

“Actually it (the referendum) was even more dangerous because, under the umbrella of national slogans calling for freedom of self-determination, Iraq almost entered a dark corner and it paved the way to cut off a large area of its territory,” A’atoani said.

Baghdad has responded by launching a huge military campaign to drive the Kurdish forces out of Kirkuk, its oil fields and most of the disputed areas. It has imposed a series of punitive measures on the region, including the banning of international flights to and from airports and the closing down of border crossings with Turkey and Iran.

“Gaining back control over the disputed areas and oil fields, shutting down the airports and crossing borders in the region is a major achievement and proved that the Iraqi government is capable of confronting anything that threatens the unity of the country and affects its sovereignty,” A’atoani said.

The year was not limited to military and political achievements. The policy of non-interference in the affairs of other countries in the region, which Abadi has adopted since he became prime minister, has also begun to bear fruit.

The Iraqi-regional relationship has significantly improved in 2017. Abadi has made several regional and international rounds during the past two months, culminating in the signing of several economic, security and military agreements with Turkey, France, Iran, Jordan and other countries.

The most important breakthrough for Iraqis was the improvement of relations between Baghdad and Riyadh, which had been fluctuating for the past three decades.

In February this year, Saudi Foreign Minister Adel Al-Jubeir was the first senior Saudi official to visit Baghdad since 2003.

Al-Jubeir’s visit was followed by a visit from Abadi to Saudi Arabia in June and another one in October to end the boycott between the two countries.

The visits opened the door for the countries to exchange visits and sign joint agreements, particularly in the oil, reconstruction, transport and anti-terrorism sectors. Last month, Saudi Arabia appointed Abdul Aziz Al-Shimari as the new ambassador to Iraq.

“Saudi-Iraqi rapprochement will ease the sectarian strife inside Iraq and deprive the Iraqi rival parties of playing the sectarian card,” Abdulwahid Tuama said.

“Also, it (rapprochement) will bring much economic gain to both countries. Iraq is looking to reach the ports of the Red Sea to export its oil, in return it can offer significant investment opportunities for Saudi companies and goods in many areas and sectors,” Tuama said.

Iraq ‘out of neck of the bottle’ by end of 2017: political analysts

Iraq ‘out of neck of the bottle’ by end of 2017: political analysts

Armenia, Azerbaijan to meet for peace talks in UAE Thursday

Baku and Yerevan fought two wars over the disputed Karabakh region, which Azerbaijan recaptured from Armenian forces in a lightning offensive in 2023, prompting the exodus of more than 100,000 ethnic Armenians.

The arch foes agreed on the text of a comprehensive peace deal in March, but Baku has since outlined a host of demands — including amendments to Armenia’s constitution to drop its territorial claims for the Karabakh — before signing the document.

On Wednesday, the Armenian government said Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev will meet the following day in the UAE capital, Abu Dhabi, “within the framework of the peace process between Armenia and Azerbaijan.”

The Azerbaijani presidency issued an identical statement.

The announcement came a day after US Secretary of State Marco Rubio expressed hope for a swift peace deal between the Caucasus neighbors.

Aliyev and Pashinyan last met on the sidelines of the European Political Community summit in Albania in May.

Iraq’s Kurdistan enjoys all-day state electricity

- The region’s electricity minister, Kamal Mohammed, said residents were now enjoying “uninterrupted, cleaner, and more affordable electricity”

Irbil: More than 30 percent of Iraq’s autonomous Kurdistan region now has 24-hour state electricity, authorities said Thursday, with plans to extend full coverage by the end of 2026.

The northern region of Kurdistan has long promoted itself as a haven of relative stability in an otherwise volatile country.

Despite Iraq’s vast oil wealth, the national grid struggles to meet demand, leaving most areas reliant on imported energy and subject to frequent power cuts.

“Today, two million people across the Kurdistan region enjoy 24-hour electricity... that’s 30 percent of the population,” including the cities of Irbil, Duhok and Sulaimaniyah, said regional prime minister Masrour Barzani.

In 2024, the Kurdistan Regional Government launched “Project Runaki” to deliver round-the-clock power in a region where, like much of Iraq, residents often turn to costly and polluting private generators.

The region’s electricity minister, Kamal Mohammed, said residents were now enjoying “uninterrupted, cleaner, and more affordable electricity.”

“Rollout to other areas is expected to be completed by the end of 2026,” he told AFP.

As part of the transition, roughly 30 percent of the 7,000 private generators operating across Kurdistan have already been decommissioned, he said, a move that has contributed to an estimated annual reduction of nearly 400,000 tons of CO2 emissions.

The project also aims to lower household electricity bills, offering a cheaper alternative to the combined cost of grid power and private generator fees.

However, bills will still depend on consumption and are likely to increase during peak summer and winter months.

Mohammed said the project’s success hinges on the introduction of “smart” meters to curb electricity theft, as well as a new tariff system to promote responsible usage.

“More power has been added to the grid to support 24/7 access,” he said.

Kurdistan has doubled its gas production in the past five years, and most of the power supply comes from local gas production, Mohammed said.

Despite Iraq’s abundant oil and gas reserves, years of conflict have devastated its infrastructure.

The country remains heavily reliant on imports, particularly from neighboring Iran, which frequently interrupts supply. It also imports electricity from Jordan and Turkiye, while seeking to boost its own gas output.

“We stand ready to offer our technical support and assistance” to the federal government, Mohammed said.

In Irbil, resident Bishdar Attar, 38, said the biggest change was the absence of noisy and polluting generators.

“The air is now clear,” he said. “We can now use home appliances freely... as needed.”

40 Palestinians killed in Gaza as Netanyahu and Trump meet over a ceasefire

- Israel’s offensive in Gaza has killed more than 57,000 Palestinians, more than half of them women and children

- Many Palestinians are watching the ceasefire negotiations with desperate for an end to the war

DEIR AL-BALAH: At least 40 Palestinians were killed in Israeli airstrikes in the Gaza Strip, hospital officials said Wednesday, as international mediators raced to complete a ceasefire deal.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had a second meeting in two days with US President Donald Trump at the White House on Tuesday evening. Trump has been pushing for a ceasefire that might lead to an end to the 21-month war in Gaza. Israel and Hamas are considering a new US-backed ceasefire proposal that would pause the war, free Israeli hostages and send much-needed aid into Gaza.

Nasser Hospital in the southern city of Khan Younis said the dead included included 17 women and 10 children. It said one strike killed 10 people from the same family, including three children.

The Israeli military did not comment on specific strikes, but said it had struck more than 100 targets across Gaza over the past day, including militants, booby-trapped structures, weapons storage facilities, missile launchers and tunnels. Israel accuses Hamas of hiding weapons and fighters among civilians.

Struggle to secure food and water

Many Palestinians are watching the ceasefire negotiations with trepidation, desperate for an end to the war.

In the sprawling coastal Muwasi area, where many live in ad-hoc tents after being displaced from their homes, Abeer Al-Najjar said she had struggled during the constant bombardments to secure sufficient food and water for her family. “I pray to God that there would be a pause, and not just a pause where they would lie to us with a month or two, then start doing what they’re doing to us again. We want a full ceasefire.”

Her husband, Ali Al-Najjar, said life has been especially tough in the summer, with no access to drinking water in a crowded tent in the Middle Eastern heat. “We hope this would be the end of our suffering and we can rebuild our country again,” he said, before running through a crowd with two buckets to fill them from a water truck.

People chased the vehicle as it drove away to another location.

Amani Abu-Omar said the water truck comes every four days, not enough for her dehydrated children. She complained of skin rashes in the summer heat. She said she was desperate for a ceasefire but fears she would be let down again. “We had expected ceasefires on many occasions, but it was for nothing,” she said.

The war started after Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, killing around 1,200 people and taking 251 hostage. Most of the hostages have been released in earlier ceasefires. Israel’s offensive in Gaza has killed more than 57,000 Palestinians, more than half of them women and children, according to Gaza’s Health Ministry.

The UN and other international organizations see its figures as the most reliable statistics on war casualties.

Netanyahu and Trump meet again

Netanyahu told reporters in the Capitol on Tuesday that he and Trump see “eye to eye” on the need to destroy Hamas. He added that the cooperation and coordination between Israel and the US is currently the best it has ever been during Israel’s 77-year-history.

Later this week, Trump’s Mideast envoy, Steve Witkoff, is expected to head to the Qatari capital of Doha to continue indirect negotiations with Hamas on the ceasefire proposal.

Witkoff said late Tuesday that three key areas of disagreement had been resolved, but that one key issue still remained. He did not elaborate.

After the second meeting, Netanyahu said he and Trump also discussed the “great victory” over Iran from Israeli and American strikes during the 12-day war that ended two weeks ago.

“Opportunities have been opened here for expanding the circle of peace, for expanding the Abraham Accords,” said Netanyahu, referring to normalization agreements between Israel and multiple Arab nations that were brokered by Trump in his first term. Washington has been pushing for normalization between Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Greek ship sinks off Yemen after Houthi attack, crew being rescued, sources say

- Some of the crew were in lifejackets in the water and at least five people have been rescued so far

ATHENS: The Liberia-flagged, Greek-operated bulk carrier Eternity C has sunk after a Houthi attack off Yemen, four maritime security sources told Reuters on Wednesday, and efforts to rescue the crew were under way.

Some of the crew were in lifejackets in the water and at least five people have been rescued so far, two of the sources said.

Jailed PKK leader Ocalan says armed struggle with Turkiye over

- Ocalan urged Turkiye’s parliament to set up a commission to oversee disarmament and manage a broader peace process

Abdullah Ocalan, the jailed leader of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), appeared in a rare online video on Wednesday to say the group’s armed struggle against Turkiye has ended, and he called for a full shift to democratic politics.

In the recording, dated June and released by Firat News Agency, which is close to the PKK, Ocalan urged Turkiye’s parliament to set up a commission to oversee disarmament and manage a broader peace process.

The PKK, which has waged an insurgency against the Turkish state for 40 years and is labelled a terrorist organization by Turkiye, the United States and the EU, decided in May to disband after an initial written appeal from Ocalan in February.

“The phase of armed struggle has ended. This is not a loss, but a historic gain,” he said in the video, the first time since he was jailed in 1999 that either footage of him or a recording of his voice has been released.

“The armed struggle stage must now be voluntarily replaced by a phase of democratic politics and law.”

Ocalan, seated in a beige polo shirt with a glass of water on the table in front of him, appeared to read from a transcript in the seven-minute video. He was surrounded by six other jailed PKK members all looking straight at the camera.

He said the PKK had ended its separatist agenda.

“The main objective has been achieved – existence has been acknowledged,” he said. “What remains would be excessive repetition and a dead end.”

Ocalan added that Turkiye’s pro-Kurdish DEM Party, the third largest in parliament in Ankara, should work alongside other political parties.