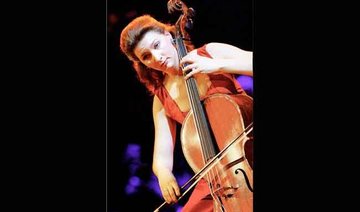

Whether viewed as an entrepreneur, a musician or a philanthropist, Tala Badri is an inspirational figure.

As the founder of Dubai’s game-changing Centre for Musical Arts (CMA), she invented the ideal vehicle to channel all these callings into the cause she holds most dear.

Touching thousands of young lives over the past decade, Badri has proved to be a pioneer of music education in the Gulf.

Her efforts have earned a shelf of business awards, which is remarkable given that the CMA is run as a non-profit organization.

The Emirati altruist has directed resources toward leading outreach programs for disadvantaged street children in Cambodia and young Palestinian refugees.

“Someone recently offered to buy (my business) out, but they would’ve totally destroyed it,” laughed the 45-year-old.

“Their concept of music education was to run it like a pure business. I was absolutely mortified.

“I was like, ‘that’s not happening. I don’t care how much money I’m not going to make, I’m not going to hand over something I’ve built for more than 11 years and let you ruin it’.”

Badri first began breaking down doors while still a teenager, when she became the first Emirati to pursue a university education in music, some quarter-century ago, after her parents battled for government funding to study abroad.

“It was tough. My mum and dad had to go in and fight for me to study music, really fight for it. If they hadn’t, I’d be somewhere very different today,” she said.

The campaign was rewarded when Badri later graduated from Royal Holloway, University of London, in 1995.

To this day, she remains the only Emirati woman to earn a degree in music. “It’s very sad, because it shows in 25 years nothing has changed,” she said.

“When people see music as something important that develops a person, not a frivolous hobby, that’s when it’s truly changed.

“We need recognition of what music gives you in terms of softer skills. More and more employers are looking for the ability to think artistically.

“From a business perspective, they’re looking for a sense of cursivity, rather than just a business degree, in getting people to think outside the box.”

Badri has certainly done her bit toward the battle. After earning a second degree in management and languages, then spending 10 years working for international brands in the financial and consumer sector, she had assembled the skills to pursue her calling.

On the back of a small business loan, the CMA was founded in September 2006 with just six teachers.

Within a month all classes were full, and by the end of the year the school’s waiting list had swelled to almost 150, proof of the undernourished arts education at the time.

Within two years 1,200 pupils had enrolled, and the CMA today employs 40 staff and works alongside 16 schools.

Along the way, Badri’s achievements have been repeatedly hailed by the male-dominated, bottom line-driven business community — ironically, as she invests all profits into the center, merely paying herself a teacher’s salary.

In 2010, she won both Best Emirati Entrepreneur and Best Female Entrepreneur at the Gulf Capital SME Awards, the same year she was asked to speak at TEDxDubai 2010.

A year later, she was invited to an audience with Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden while in town to pick up a Certificate of Appreciation Award.

Badri has also been named a Patron of the Arts and a Friends of the Arts by her hometown authorities, and in 2013 the CMA was named Emirati Business of the Year at Gulf Capital.

“I get a lot of recognition from a business perspective. I’ve built a business and seen it through two financial downturns. I know how hard it is to be an entrepreneur,” she said.

“I could go into consulting and make shedloads of money. I could make anyone else’s business work, but I don’t want to. I want to make my own business work.

“I still feel I haven’t achieved what I really want to do until I feel that the concept of music education in the region has really changed.

“Performing arts in general aren’t looked on favorably. It’s seen as flaunting yourself, putting yourself out there. I want it to become the norm.”

One might call Badri a social entrepreneur. In August, she will lead the CMA’s sixth annual expedition to Siem Reap, Cambodia, to work with street children at an orphanage run by the Green Gecko Project.

A team from the school has also travelled to Lebanon to work with children in a refugee camp administered by the Palestine Children’s Relief Fund (PCRF). The CMA has hosted visiting children from both projects in Dubai.

“You have to do it to understand what it does to you as a person. All those who’ve come with us to Cambodia have come back changed and completely reenergized in how they think about things,” said Badri.

“Teaching is a very self-sacrificing job. You become a teacher because you’ve got a talent and a skill, but we normally teach very privileged children, and it’s so different to work with children so underprivileged but so hungry to learn.

“It’s one of the most satisfying things you can do as a person, to see that you can make another person smile or sing. It’s incredibly rewarding.”

Find out how this Emirati entrepreneur makes a difference with music

Find out how this Emirati entrepreneur makes a difference with music

Saudi designer Honayda Serafi shares holiday greeting card from Jordan’s Crown Prince Hussein and Princess Rajwa

DUBAI: Saudi designer Honayda Serafi has revealed a holiday greeting card from Jordan’s Crown Prince Hussein bin Abdullah and Princess Rajwa Al-Hussein, which features a family photo of the royal couple and their newborn daughter, Princess Iman.

“Immensely thankful for God’s many blessings. From our small family that has grown to yours, best wishes for a blessed New Year,” the card reads.

Last year, Serafi designed Saudi-born Princess Rajwa’s pre-wedding henna night gown. For the gown, Serafi took inspiration from the Al-Shaby thobe of the Najd region in Saudi Arabia, where Princess Rajwa’s family is from.

“The thobe is known for its long sleeves. They’re so long, the sleeves become the veil of the bride’s dress,” said Serafi of the ethereal white gown.

Earlier this month, the couple visited the Seeds of Hope Center in Amman, which specializes in treating speech and language disorders in children and adults.

The royal couple, who welcomed their first child this year, toured the facility, which houses Jordan’s only space designed to provide multi-sensory experiences aimed at promoting relaxation and sensory integration. The visit also included a look at the center’s gym, which is tailored to improve therapy outcomes for patients, the Jordan News Agency reported.

Aya Al-Jazi, the center’s director, briefed the couple on the facility’s services, which include evaluation and treatment of speech, language and voice disorders, as well as support for swallowing difficulties.

Sister act: Saudi sibling filmmakers Raneem and Dana Almohandes talk musicals, inspiration and telepathy

JEDDAH: A trip to Saudi Arabia’s AlUla, a chance encounter with a persistent mosquito on the streets of New York and an enduring love for musicals inspired Saudi filmmaking sisters Dana and Raneem Almohandes to create their animated short film “A Mosquito,” which screened at the recently concluded Red Sea International Film Festival in Jeddah.

“We were walking in New York, having a good time, and there was this mosquito who kept coming back to me,” explained older sister Raneem. “This is how it all started, with one question: ‘What does this mosquito want?’ We thought, ‘She wants to talk to us, but we’re not giving her the chance.’ So, that’s where the story was born.”

Set in 1969, “A Mosquito” follows Zozo — a tiny mosquito with big dreams. While her peers are content with ordinary life in the majestic landscapes of AlUla, Zozo dares to dream of becoming a famous singer — heading to Egypt to sing before the legendary Umm Kulthum.

“A Mosquito” began life as a two-minute short — part of Raneem’s university project. It turned into its fully realized version after they took their idea to the AlUla Creates program, a local initiative that provides funding, mentorship and networking opportunities for Saudi filmmakers and fashion designers.

“When AlUla invited us to apply, we had this idea already, and we wanted to expand on it, because, you know, university projects are victims of time and resources. We developed the story with the AlUla Creates team,” said Raneem.

“We went to AlUla earlier, and we captured the aesthetics from there. The frames that you see in the film are identical to the pictures we took during our trip,” added Dana.

Raneem graduated from New York University in musical theater writing (Dana, the younger of the two, is studying filmmaking at Princess Nourah Bint Abdul Rahman University in Riyadh). “We grew up watching musicals, but we felt like we don’t have any that are in the Saudi dialect, so we wanted to create (them),” said Raneem. “That’s why I studied musical theater writing.

“We’ve always loved expressing ourselves through art. For example, Dana will do a dance whenever she wants to express how she feels about someone. Like, for my birthday, she would do a choreographed dance. I used to do small videos for our family — sometimes they’re music videos, sometimes short films … this is how we started. And then I started an Instagram page for DIY videos, and we worked together on it. It was one of the first (Instagram accounts) to reach 1 million followers in the Middle East,” said Raneem. “Dana was, like, 10 years old back then.”

Before they had received any formal training, the duo were chosen as For Change Ambassadors of Saudi Arabia. The screenplay for their first musical feature (“Dandana”) was shortlisted in the second round of Sundance’s Screenwriters Lab 2020. Their first short, “A Human,” was funded by Google and premiered in Riyadh.

The sisters reiterate that their filmmaking career is closely tied to the history of cinema in the Kingdom.

“We put ‘A Human’ up on YouTube in parallel with Saudi Arabia opening its cinemas again,” Raneem said. It went on to become one of the first 100 films to be shown in cinemas after they reopened in the country and, according to Raneem, the very first short film.

In 2022, the pair wrote and directed the musical short “A Swing,” which was selected for the official competition at the Saudi Film Festival and was screened as part of the Kingdom’s participation at Cannes in 2022.

Despite the eight-year age gap between the two sisters, the duo say they have a seamless working relationship.

“We sometimes fight, as all sisters do, but we have telepathy most of the time,” said Raneem. “We are in sync in terms of ideas. Filmmaking is all about communication.”

Working as two young women in the Saudi film industry is, Dana said, “magical.” Raneem agreed.

“It’s overwhelmingly beautiful, because the support is magnificent,” she said. “Each and every project and idea that we’ve had, we knew for a fact that if we approached the right decision maker, it would happen.”

REVIEW: ‘S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2: Heart of Chornobyl’ tells a story of resilience and survival

LONDON: “S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2: Heart of Chornobyl,” developed by Ukrainian studio GSC Game World, stands as both a gripping survival adventure and a reflection of real-world resistance in the face of adversity.

The game’s development faced significant challenges, with the studio partially relocating to the Czech Republic due to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. This struggle has imbued the game with poignant cultural references and an atmosphere shaped by the harsh realities of its creators’ circumstances.

Players assume the role of Skif, a Ukrainian Marine Corps veteran drawn into the “Zone,” a dystopian take on the Chernobyl exclusion zone. In this alternate universe, the infamous nuclear disaster unleashed not only radiation but also space-time anomalies and a host of mutated threats.

The Zone is merciless, and so is the gameplay. Stalkers — explorers of this treacherous area — must navigate its dangers in pursuit of adventure, profit or ideology. The game emphasizes survival, with a steep learning curve that demands careful planning. From radiation and traps to scarce resources and malfunctioning weapons, every step is fraught with danger. Deaths are frequent and the game tracks your fatalities, adding to the sense of vulnerability.

The game shines in its atmospheric design and mechanics. The 64 sq. km open-world setting is a stunning yet haunting playground for chaos. Weapon handling is top notch, and the enemy AI is intelligent and challenging. The various human factions and mutant creatures add layers of unpredictability to the experience, while side missions pile up in classic open-world fashion.

However, the game is not without its flaws. Some elements feel restrictive, limiting creativity in problem-solving. For instance, mutant dogs may attack you relentlessly while ignoring nearby enemies. Invisible anomalies that kill instantly and radiation-related deaths can feel arbitrary, especially early on when resources like health kits and food are scarce. Additionally, the dialogue leans on cliches, which may detract from the storytelling for some players.

Despite its challenges, “S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2: Heart of Chornobyl” offers a deeply rewarding experience for those willing to persevere. The unforgiving difficulty and grounded survival mechanics create a palpable sense of tension, while the evocative setting offers a mix of chaos and beauty. Fans of open-world games, particularly those craving a grittier and more challenging experience, will find much to appreciate.

Born out of extraordinary circumstances, it is more than just a game — it’s a testament to the resilience and creativity of its developers. Stick with it, and you will discover a truly unique title forged in the most difficult of times.

Imposing ‘dala’ pickup trucks symbolize Pakistan’s power gulf

- Hilux has become a symbol of power, affluence and intimidation in a society marked by significant class divisions

- “Dala,” as it is locally known, also serves as euphemism for military intelligence agencies involved in covert operations

KARACHI: In Pakistan’s largest city, cars inch forward in bumper-to-bumper traffic. But some seamlessly carve through the jam: SUVs flanked by Toyota Hilux pickup trucks.

The Hilux has become a symbol of power, affluence and intimidation in a society marked by significant class divisions.

“The vehicle carries an image that suggests anyone escorted by one must be an important figure,” 40-year-old politician Usman Perhyar told AFP.

“It has everything — showiness, added security and enough space for several people to sit in the open cargo bed.”

On Karachi’s chaotic roads, Hiluxes part the traffic, speeding up behind cars and flashing their lights demanding drivers move out of their way.

The Hilux first became popular among feudal elites for its reliability in rural and mountain regions.

But in recent years, the “Dala,” as it is locally known, has soared in popularity as an escort vehicle among newly successful urban business owners.

Guards with faces wrapped in scarves and armed with AK-47s can be packed into the back of the truck, its windows blacked out.

“It is a status symbol. People have one or two pickups behind them,” said Fahad Nazir, a car dealer based in Karachi.

The Hilux debuted in 1968, but the model that became popular in Pakistan was the mid-2000s Hilux Vigo.

It was later upgraded and rebranded as the Revo, with prices ranging from 10 to 15 million rupees (approximately $36,000 to $54,000).

Their prices have remained steady and they retain excellent resale value in a market traditionally dominated by their manufacturer, Toyota.

“Amongst whatever luxury items we have, this is the fastest-selling item,” car seller Nazir told AFP.

Dealers say there was a spike in rentals during February’s national elections.

“I swear to God, you can’t run an election without a Revo,” said Sajjad Ali Soomro, a provincial parliamentarian from Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party.

In the eastern city of Gujrat, politician Ali Warraich — from the ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz party — finds it essential to travel with an escort of two of the trucks.

They allow him to navigate off-road terrain to attend dozens of weddings and funerals a month.

“Politics without this vehicle has become nearly impossible,” he tells AFP. Without one, he argues, potential supporters could question his influence and turn toward competitors.

“As a result, it has become a basic necessity,” he said.

The truck has also become a trademark in the suppression of dissenting voices, activists told AFP, with the word “Dala” serving as a euphemism for military intelligence agencies involved in covert operations.

The unmarked cars with plainclothes men inside were used extensively by authorities rounding up senior PTI leaders and officials in recent crackdowns — reinforcing the vehicle’s notorious reputation.

“Every time I see this vehicle on the road, I go through the same trauma I endured during my custody with agencies,” said one PTI member who was picked up earlier this year.

Former leader Khan was bundled into a black Dala by paramilitary soldiers when he was arrested in May 2023 in the capital Islamabad, a detention he blamed on the powerful military leadership.

He later accused political heavyweight and three-time prime minister Nawaz Sharif of trying to win the election “through Vigo Dala” — a swipe alleging the military was “carrying” his campaign.

Pakistani poet and activist Ahmad Farhad, known for criticizing the military’s involvement in politics, was taken away in a Hilux after a raid on his home in May by what he said were intelligence agencies.

“Sometimes, they park these vehicles around or behind my car, sending a clear message: ‘We are around’,” he told AFP. “A Dala aligns with their business of spreading fear, which they take great satisfaction in.”

In Karachi, a city rife with street crimes, the imposing Dala deters even outlaws.

“A typical mobile snatcher would opt for maybe looting a car as opposed to a truck,” said 35-year-old automobile enthusiast Zohaib Khan.

Increased street crime has led to more security checks by police, further slowing down movement across the city. But Hiluxes are immune.

Police “don’t typically stop me because they feel that I might be someone who might impact them in a bad way or harm them in some way or the other,” Khan said.

British historian explores Nabateans’ ‘cool culture’ in documentary

- Bettany Hughes’ series ‘Lost Worlds’ travels through AlUla, Europe and Petra

JEDDAH: For British historian Bettany Hughes, the story of the Nabateans is as vital as those of the ancient Greeks, Romans or Egyptians.

In a new three-part series, “Bettany Hughes' Lost Worlds: The Nabataeans,” Hughes traces the titular civilization’s incense trade routes from the Arabian Peninsula to the Mediterranean, accessing newly revealed research across Saudi Arabia’s Al Ula, Jordan, Greece, Italy and Oman.

“For me, you can’t understand the classical world unless you understand the Nabataeans — they are the missing link in the story of society, because, in many ways, they were the engine that drove many other civilizations. They connected the far edges of the Arabian Peninsula with the center of Europe, and without them, that line of connection wouldn’t have happened,” Hughes told Arab News on the sidelines of this month’s Red Sea International Film Festival, where the show’s first episode was screened.

Her decades of research have revealed that Petra, the Nabateans’ iconic capital, was just a small part of a vast empire that is only now revealing its secrets.

“When you say, ‘These are the guys that built Petra,’ then people go, ‘Oh, yeah. I always wondered.’ But that’s why we’re doing this series; to remind the world that they have this whole other story, whole other centers of operation. And to try to write them back into history. They’re a very cool culture. I’m very impressed by them.

“They love happiness. They love liberty. Women seem to have a really strong role in their society. They’re all about trade and communication — and therefore understanding people beyond borders and boundaries. So, I think there’s a lot that we can learn from them as a culture,” she continued.

Hughes’ entry point to the Nabateans came almost three decades ago.

“It was initially through trying to do detective work on the trade network,” she explained. “I knew that the Romans were obsessed with incense. I knew that Tutankhamun was buried with incense balls in his tomb. And I thought, ‘So, who’s delivering that?’ Because I also knew that incense came from that southern edge of the Arabian Peninsula. So, who was in charge?

“And then I saw this coin of Aretas IV, who was probably the most powerful of all the Nabatean kings. And Huldu, his queen, was also on the coin. And I just thought that that doesn’t happen often. That’s really interesting, so I needed to get to the bottom of their story,” Hughes added.

And since Saudi Arabia’s AlUla has been opened up to the outside world over the past few years, Hughes jumped on the opportunity to learn more about the civilization that’s recurrently appeared on the edges of her research efforts.

She first travelled to the historic site in 2022, heading deep into the deserts of AlUla, even spending time with the still-existing Bedouin communities there, tracing how the Nabateans traversed the harsh landscape with their camels and the stars as guides.

The first episode of “Lost Worlds” is dedicated entirely to AlUla, in the second episode they visit Europe, before heading to Petra in the third and final episode.

Hughes credited her love for history to one of her schoolteachers.

“When I was growing up, history wasn’t fashionable. People would say, ‘Oh, it’s irrelevant. All the answers lie in the future.’ And I just knew that couldn’t be true — that there was this reservoir of ideas and inspiration and understanding that came in the past,” she said. “And then I had a brilliant teacher who said, ‘Go for it. Even if you’re unpopular, even if people are saying no, make it happen.’ That kind of gave me the confidence to plow ahead.

“I then went to Oxford to study history, and I was very aware that in the official stories of the world that I was reading as a student, women didn’t feature very much. Even though I knew, obviously, we’d been 50 percent of the human population forever, we only occupied a tiny percentage of recorded history. So I felt that was something I could help with,” she continued. “I don’t just write about women’s history, but I’m always looking for the gaps — and the story of the female role in history is one of those gaps that needs filling.”