Fair director Myrna Ayad was not joking when she said this 12th edition of Art Dubai has a jam-packed program. It is the biggest in terms of sheer numbers, with 105 galleries from 48 countries participating. This ensures a truly global representation, with an impressive roster of galleries — established and emerging — from around the world. This year’s Art Dubai also marks the debut for four countries: Ethiopia, Ghana, Iceland and Kazakhstan.

The diversity extends to the variety of art too, ranging from works by established masters dating back to the 1920s on display at Art Dubai Modern, to avant-garde installations in the contemporary section.

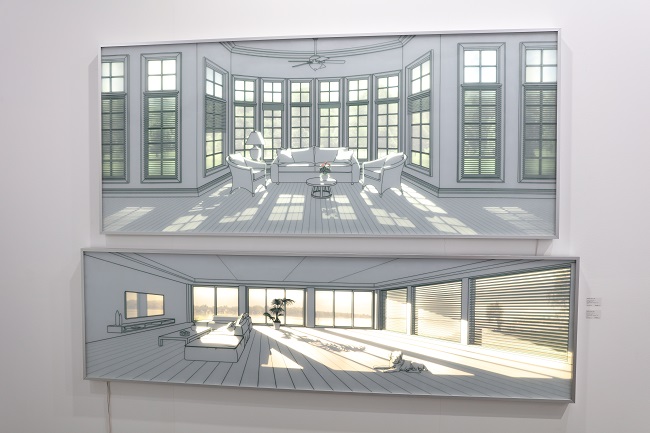

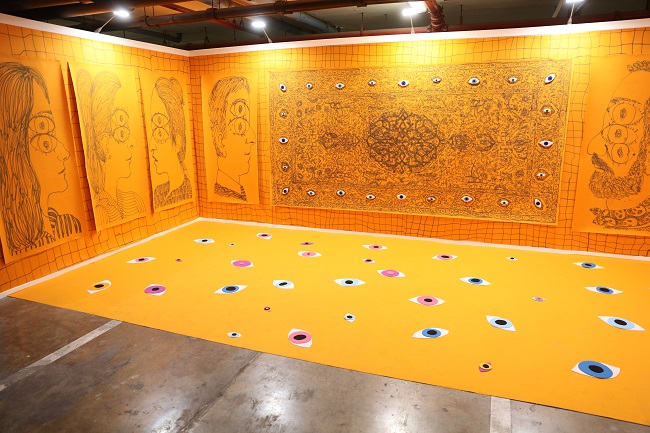

In fact, traditional canvases seemed to be the exception rather than the rule in this cornucopia of creativity, with a range of materials being used in unexpected ways to produce art — from reclaimed steel, acrylic, ceramic and brass inlay in concrete, to textile, polyamide, and of course digital media.

It is practically impossible to pick favorites from the numerous pieces, as everyone interprets and appreciates each one differently, but there is a distinct focus on art from Africa, South Asia, and of course the Middle East. Particularly worth checking out is the Hafez Gallery from Jeddah, which has brought noteworthy pieces from artists such as Abdulsattar Al-Mussa and Thuraya Al-Baqsami to the fair.

As artistic director Pablo del Val advises, start with the Modern section, then work your way through the contemporary gallery halls, but most importantly, come with an open mind. “Leave any prejudgment out and follow your heart and brain. That’s when it will really come alive,” he said.

Having built up a reputation as a fair for discovery, where many new and emerging artists are given a platform, this year Art Dubai has introduced a Residents program that invited 11 artists from around the world to spend a few weeks in the UAE, in collaboration with three art spaces — Tashkeel, in5 and Warehouse 421 — to create a body of work inspired by their time in the country.

According to Saudi artist Faris Al-Osaimi, it was a challenging but rewarding experience. “It was really difficult at first working outside my own studio, but I learnt a lot working with the other artists, including experimenting with different techniques,” he said.

Another artist who participated in the Residents program, Tato Akhalkatsishvili, aims to tackle the bilateralism of human beings and the environment with his large oils on canvas. “I created a series titled ‘Is your body a heaven,’ in which I explore living organisms and objects of nature in abstract ways,” he said.

His is the sort of work that is likely to appeal to a new generation of collectors who, as most art experts agree, are more adventurous in their choices, and buy art that they like to hang on their walls rather than simply collecting big names for collecting’s sake.

In a clear bid to make art less elitist and more engaging with the greater community, Art Dubai’s programing this year includes a rich mix, ranging from the TV show-style activation at The Room, Good Morning GCC, to taking on the omnipresent subject of artificial intelligence with Global Art Forum’s “I am not a robot” theme.

The Global Art Forum — with its thought-provoking curation of talks by Shumon Basar, Noah Raford from the Dubai Future Foundation, and Marlies Wirth, curator of digital culture at the MAK, Vienna — may have left us with more questions than answers, but that was kind of the point.

The art collective GCC leverages the popularity of people outside the art world — think TV stars such as Suliman Al-Qassar — and delves into the aesthetics, politics and practices of Gulf culture within the immersive format of a daytime talk show, with segments covering cookery, fashion, holistic wellbeing and happiness, in a green screen-inspired set.

The interactive performances, which involve audience members getting to try the food being cooked, “have a universal appeal outside the context of art audiences,” said Barak Al-Zaid, a member of the collective.

Ayad is understandably excited about this innovative feature of the fair. “It’s always exciting to commission an artist to create something, but to tell them to take over a space and transform it with performance, with gastronomy… I think it’s brilliant that we can offer such a platform.”

Also providing a platform were the fair’s key partners. Emirati artist and designer Jawaher Al-Khayyal was commissioned by Piaget to create the interactive installation “Summer muse,” inspired by the “Sunny side of life” high-jewelry collection.

“It’s a seat that twirls, with reflective light off a brass rim that casts a shimmering shadow and gives a magical effect,” said Al-Khayyal. “The movement is inspired by the natural movement of feathers, leaves and water.”

Swiss-Egyptian artist Karim Noureldin’s creation was a site-specific installation for the Julius Baer lounge, titled “From pen to thread, Des.” The abstract textile installations, one of which is an ambitious 40 square meters in size, have been hand-woven in India. “I’ve done something that I felt would transmit some kind of serenity, a visual object that conveys calm,” said the artist.

The Sheikha Manal Little Artists Program sees Japanese-Australian artist Hiromi Tango working with children in her project Healing Garden, which features local plants and flowers.

Showing just how far Art Dubai has come since its inception, this year’s edition marked the 10th anniversary of the annual Abraaj Group Art Prize (AGAP). The winner of this year’s prize, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, is pushing boundaries — both contextually and in terms of the technology employed — in his audio-visual installation exploring divisiveness between nations and people.

This year, AGAP also announced its partnership with Art Jameel, wherein their full collection of the past 10 years will be given on long-term loan to the Jameel Arts Center, set to open in Dubai later this year.

Another exciting collaboration birthed at this year’s iteration of the fair was one with the ambitious Misk Art Institute from Saudi Arabia. A highlight of this partnership is “That feverish leap into the fierceness of life.”

It is a non-selling exhibition that shows, perhaps for the first time, the panorama of modern art in the Arab world by showcasing five Modernist art schools or movements that emerged between the 1940s and 1980s from five Arab cities: Baghdad, Cairo, Casablanca, Khartoum and Riyadh. The intriguing nomenclature of the exhibition owes its origin to a manifesto of the Baghdad group of modern art, and is meant to represent the role of art in social change.

The Misk partnership also saw the regional premier of a virtual reality film on contemporary art in Saudi Arabia, “Reframe Saudi”; exclusive sessions in the Modern Art symposium; and limited-edition publications.

Nada Al-Tuwaijri, head of communications at the Misk Art Institute, said: “A very important aspect of the art world is building connections. Art Dubai is considered a hub, so this is an excellent networking opportunity for us as a very young organization, a push for building key relationships in the future.”

She sums up the spirit of the fair aptly which, while very much a space for commercial art activity, is more importantly a global meeting point, a place for people to converge and converse.