ROTTERDAM: I can distinctly remember the first time I heard Anouar Brahem’s playing because the circumstances were so cinematically odd. As a wanderlust-struck student sitting in a café in Tangier, Morocco – a day after finishing a three-week sponsored hitchhike from London – a sketchy-seeming local smoking butts struck up a rapport and insisted on taking me to a nearby pirate CD shop, where he demanded the owner put on his favorite album.

The sounds which spiraled from the speakers were magical — a spellbinding, spiritual swirl of oud, woodwind and percussion unlike anything I’d ever heard before. I bought the album on the spot, for less than 3 SAR (80 US cents). It was called “Madar” and was co-credited to Norwegian saxophone star Jan Garbarek, Pakistani tabla maestro Ustad Shaukat Hussain — and Tunisian oud virtuoso Anouar Brahem. That moment was to kickstart a lifelong love of the latter instrument — and the record label that facilitates and fuels such fascinating fusions, ECM — but Brahem will always be the one who stole my heart first.

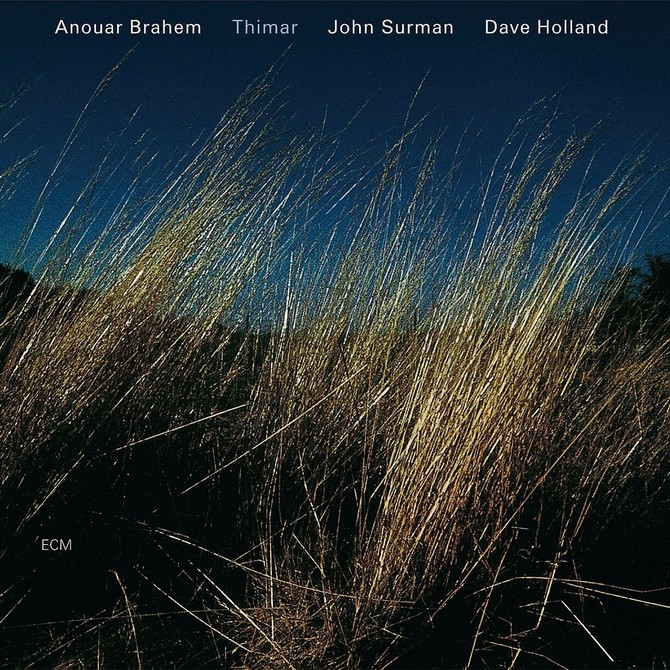

May (18th) marks the 20th birthday of “Thimar,” arguably the most enduring recording of Brahem’s glittering, three-decade international career. Brazenly paired alongside two distinguished English jazzmen — bassist Dave Holland and saxophonist/clarinetist John Surman — the “transcultural” conceit exemplifies Brahem’s restless mission to transplant Arabic classical music traditions into an international, improvisational context.

It is intensely chilled. Brahem’s sparse, maqam themes offer a skeleton frame for collective sound-scaping of the most intuitive kind: Holland’s low growls and Surman’s plaintive cries a sympathetic sonic foil to the oud’s meditative meandering. Tellingly, Brahem’s is the last voice to be heard, the oud only appearing half-way through the eight-minute opener “Badhra.”

Brahem would record many equally atmospheric sessions for ECM, often shaded by the dense harmonies of a piano and/or accordion. But there’s something special about the sparseness of “Thimar,” democratically colored by three largely monophonic instruments, like three wise men in a conversation — or in the case of frenzied “Uns,” a heated debate. This is music to think to, not think about — sounds which fire up the synapses and set memories reeling into motion.