LONDON/NAIROBI: In January, the Comoros Islands quietly canceled a batch of its passports that foreigners had bought in recent years. The tiny nation off the east coast of Africa published no details of its reasons, saying only that the documents had been improperly issued.

But a confidential list of the passport recipients indicates the move meant more than the government let on. An investigation found that more than 100 of 155 people who had their Comoros passports canceled in January were Iranians. They included senior executives of companies working in shipping, oil and gas, and foreign currency and precious metals — all sectors that have been targeted by international sanctions on Iran. Some had bought more than one Comoros passport.

Diplomats and security sources in the Comoros and the West are concerned that some Iranians acquired the passports to protect their interests as sanctions crimped Iran’s ability to conduct international business. While none of the people or companies involved faced sanctions, the restrictions on Iran could still make a second passport helpful. Comoros passports offer visa-free travel in parts of the Middle and Far East and could be used by Iranians to open accounts in foreign banks and register companies abroad.

The Iranian government does not formally allow the country’s citizens to hold a second passport. However, an Iranian source familiar with the buying of foreign passports said Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence had given the green light for some senior business figures to acquire them to facilitate travel and business transactions.

The Iranian government and its embassy in London did not respond to requests for comment.

Houmed Msaidie, a former Comoros interior minister who was in office when some of the passports were issued, said he suspected some Iranians were “trying to use Comoros to get around sanctions.”

He said he had pushed for further checks before passports were granted to foreigners, but did not elaborate.

The US Treasury declined to comment, saying it did not discuss current investigations.

Kenneth Katzman, a Middle East expert at the US Congressional Research Service, said that Comoros was one of a number of African nations where Iran has tried to exert trade and diplomatic influence.

“Having a Comoros passport would allow them to do things without being flagged as Iranians,” he said.

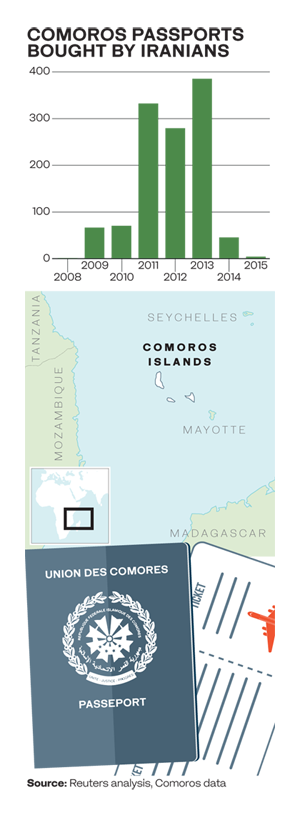

In all, more than 1,000 people whose place of birth was listed as in Iran bought Comoros passports between 2008 and 2017, according to details of a database of Comoros passports. The majority were bought between 2011 and 2013, when the international sanctions were tightened, particularly on Iran’s oil and banking sectors.

Other foreigners who bought Comoros passports include Syrians, Afghans, Iraqis, Chinese, and a handful of Westerners.

International sanctions against Iran were eased following a deal struck in 2015 aimed at preventing Iran developing nuclear weapons. In May, US President Donald Trump pulled the US out of the agreement, saying it was “defective” and a “horrible, one-sided deal.” Since then, the US Treasury has imposed fresh sanctions against people it links to Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, the nation’s missile program, some Iranian airlines and money transfer services. Further US sanctions will take effect in August and November.

The buyers

The Comoros Islands, a nation of about 800,000 people, began its program to sell passports in 2008 as a way of raising much-needed cash. The islands arranged a deal with the governments of the UAE and Kuwait, who wanted to provide stateless inhabitants there known as the Bidoon with identity documents, but not local citizenship. The governments would buy the Comoros passports, and then distribute them to the Bidoon.

In return, the Comoros was meant to receive several hundred million dollars to help develop its economy, whose output amounts to just $600 million a year.

At the time, the Comoros was also forging ties with Iran. The islands’ president from 2006 to 2011 was Ahmed Abdallah Mohammed Sambi, who had studied for years in the Iranian holy city of Qom.

Sambi had Iranians among his bodyguards, according to locals and to research by the think-tank Chatham House, and was dubbed the “Ayatollah of the Comoros” by some islanders. In 2008, he visited Tehran.

At the time, then-Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was cultivating relations with African and Latin American countries as the West turned its back on Tehran. Ahmadinejad paid a return visit to the Comoros the following year.

More than 300 Comoros passports were sold to Iranians while Sambi was in power, according to data. Sambi, who has been questioned by Comoros law enforcement as part of its investigation into the economic citizenship scheme, did not respond to requests for comment.

Sambi has been under house arrest since May 19 after being accused by the government of inciting unrest. On June 23, Jean-Gilles Halimi, a lawyer acting on Sambi’s behalf, said the restrictions placed on Sambi were an attempt by the government “to get rid of a rival.”

The passport sales continued under Sambi’s successor, Ikililou Dhoinine, who held office from 2011 until 2016. Ikililou, who has no obvious links to Iran, did not respond to requests for comment.

According to the data, Iranians who bought Comoros passports as sanctions squeezed Iran and while Ikililou held power included:

— Mojtaba Arabmoheghi, whom the government named in 2011 as one of the top managers in Iran’s oil industry. He obtained a Comoros passport in October 2014 when he was chairman of Sepehr Gostar Hamoun, an international trading company, which has not faced sanctions. In 2016, Arabmoheghi was also a commercial consultant to a company called Silk Road Petroleum. The financial director of the company, Naser Masoomian, also Iranian, acquired a Comoros passport on the same day as Arabmoheghi.

Arabmoheghi and Masoomian did not respond to requests for comment. Silk Road Petroleum did not respond to a request for comment sent via its website. Sepehr Gostar Hamoun could not be contacted via telephone numbers listed for it.

— Mohammed Sadegh Kaveh, head of Kaveh Port and Marine Services, acquired a Comoros passport in 2015. Kaveh and his family are one of the main operators of Iran’s port of Shahid Rajaee in Bandar Abbas, which handles most of Iran’s container traffic.

A spokesman for Kaveh Port and Marine Services, which has not been sanctioned, said Kaveh does not have a Comoros passport and that all the company’s services are in line with Iranian and international laws. Asked why Kaveh’s details appear in a database of Comoros passports, the spokesman said the information was “tendentious” and that it was possible someone else had used Kaveh’s name.

— Hossein Mokhtari Zanjani, an influential figure in Iran’s energy sector and lawyer who handles domestic and international disputes, acquired a Comoros passport in 2013.

Zanjani could not be reached for comment.

As it was reported last year, another person who bought a Comoros passport was Mohammed Zarrab, a gold dealer who holds both Turkish and Iranian citizenship. He was indicted in 2016 by a US court for using the US financial system to conduct hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of transactions on behalf of Iran. His brother, Reza Zarrab, pleaded guilty to similar charges and was the US government’s star witness in the trial of a Turkish banker also accused of sanctions busting. The whereabouts of Mohammed Zarrab are unclear. His lawyer, who said he was unaware of a country called the Comoros Islands, said he would try to seek a response from Zarrab but did not supply one.

Change of tack

In early 2016, the Comoros adopted a different foreign policy, severing ties with Tehran and instead supporting Saudi Arabia and other Gulf nations at odds with Iran. That May, a new administration led by Azali Assoumani came to power in the Comoros and continued the new policy.

Under Assoumani, a parliamentary commission of inquiry was set up in 2017 to investigate the program providing citizenship to the UAE and Kuwait for the Bidoon.

It has examined allegations by some of the islands’ politicians that the system was improperly implemented and undermined by corruption, with passports being sold beyond the original plan.

That investigation found, in a report published in early 2018, that the UAE informed the Comoros authorities as early as 2013 that hundreds of passports had been sold to foreigners outside the program for the Bidoon.

The issue emerged after UAE security services began spotting people who were neither Comorians nor Bidoon traveling through the Gulf country on Comoros passports, said a source who took part in the Comoros investigation. Many were Iranians, the source said. The UAE did not respond to requests for comment.

A Comoros security source said that the Comorian intelligence services had received reports of people with Comoros passports being killed on the battlefields of Iraq, Syria and Somalia in recent years. The source said this was an indication of how widely Comoros passports may have been sold.

The scale of the sales, which ran to hundreds of passports, began to worry international diplomats who monitor the tiny archipelago. An official with the US State Department in the region who is familiar with the passports program said: “We believe that Comoros didn’t do any vetting on the people who got their passports.”

The Comoros government did not respond to requests for comment.

The US now imposes more stringent checks on travelers from Comoros, the US diplomat said. He said French authorities are also concerned because thousands of Comorians reside in France and there is relatively regular travel between the two nations.

A spokesman for the French Foreign ministry said it was aware of the sale of Comoros citizenship but could not comment on it.

The sale of Comoros passports not only poses a security risk for the West but has also done less than expected for the island nation’s economy.

According to the parliamentary report, at least $100 million in revenues from the sale of passports was not received by the government and has gone missing. Foreign Minister Souef Mohamed El-Amine said: “There was money that never reached the treasury. We need the money back from the people who profited — including the foreigners.”

Belgian raid

The passports issued by the Comoros Islands were produced by a Belgian company called Semlex, which supplies identity documents to various African countries. In January, Belgian police searched the offices of Semlex in Brussels and the home of its chief executive, Albert Karaziwan, in connection with an inquiry into Semlex’s provision of passports to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

That investigation followed a news report in April last year about Congo passports. The report showed how Congo’s government was selling new biometric passports to its impoverished citizens for $180 each.

In May, Comoros law enforcement officials raided the offices of Semlex in Comoros as part of their investigation into passport sales.

Francois Koning, a lawyer representing Semlex and Karaziwan, said Karaziwan would not comment for this article and claimed, as he did with a previous news article referring to Semlex, that unidentified third parties were manipulating the media with the aim of damaging Karaziwan and his company.

Koning said: “Semlex Europe has no role in the decision to issue passports. This is the sole prerogative of the Comoros authorities who are the only authorized representatives to do so.”

He added that Semlex “is neither responsible nor to blame for the actions or acts” that are alleged in the Comoros parliamentary report on the sale of passports, “supposing they even took place.”

Some Comoros passports were marketed via a company called Lica International Consulting, according to an agreement between Lica and the Comoros Islands.

Lica’s representative is a Frenchman called Cedric Fevre, an associate of Karaziwan. Fevre and Lica did not respond to requests for comment. Henri Nader Zoleyn, a lawyer representing Fevre, said he was not aware of any activities in relation to the Comoros citizenship scheme and his client had not sought any advice on the matter.

On its website, Lica listed as a partner a Dubai-based company called Bayat Group, which is run by Sam Bayat Makou, an Iranian. According to its website, Bayat Group specializes in in providing citizenship from places such as the Comoros, Malta and St. Kitts in the Caribbean.

Makou himself acquired a Comoros passport in July 2013. That passport was one of those canceled by the Comoros government early this year. Makou said Iranians acquired Comoros passports because “Comorians have better visa-free access than Iranians” to many countries, particularly in the Far East.

He said his firm had done some work with Lica, which he said was licensed by the Comorian government to market Comoros passports outside the program for the Bidoon.

Following talks in May with US officials, the Comoros committed to sharing information about the passports issue with US agencies.

A senior US State Department official in Europe said: “We look forward to working with the government of the Comoros and other nations involved” to understand the activities that the sale of Comoros passports beyond the Bidoon scheme “may have facilitated.”

Last month, too, Comoros Interior Minister Mohamed Daoudou told local media that the scandal over the sale of Comoros passports had become an international problem. “It is a terrorism issue,” he said.

“It is not just a question that involves lots of money but also security on an international level.”