DUBAI: More than four decades ago, the Arabian oryx was extinct in the wild. But today, thanks to efforts spearheaded by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, experts are citing the swell in its numbers as one of the world’s biggest conservation success stories.

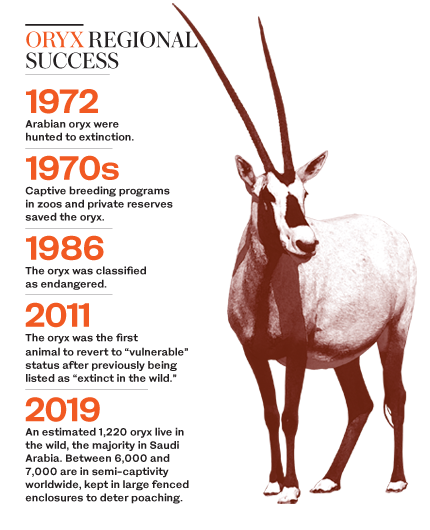

In the early 1970s, the antelope was considered all but vanished due to hunting and poaching.

Now it is not only back from the brink, but in 2011 the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) reclassified it to “vulnerable” from “endangered,” the first time a species that was once “extinct in the wild” improved in status by three full categories out of six on its Red List of Threatened Species.

There are now an estimated 1,220 wild oryx across the Arabian Peninsula, in addition to between 6,000 and 7,000 in semi-captivity.

Experts at the IUCN have revealed to Arab News that the Arabian oryx could be upgraded to another level on its list within years, to “near-threatened,” thanks to regional breeding programs and reintroduction initiatives in the Kingdom, the UAE and the wider Gulf.

“About 40 years or so ago, the Arabian oryx was extinct in the wild formally, which meant there were none of these animals left in the wild, just those in captivity or in private collections,” said David Mallon, co-chair of the IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Antelope Specialist Group.

“Unfortunately, we don’t really have very much detailed information on the past. We’ve just got plenty of anecdotal reports of oryx around, and as far as we know the species was very widespread across the whole of the Arabian Peninsula. In the north it went as far as Iraq and Kuwait, Syria in the northwest and then Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Oman and the UAE in the south,” he added.

“But as soon as motor vehicles and modern weapons arrived, the destructive potential of hunting rapidly increased. Before, if you were on a camel and you had a single shot, by the time you had another bullet in the gun the oryx would’ve run off. But when motor vehicles and more modern, reloadable rifles were introduced — you can wear oryx out through exhaustion — hunting became a lot easier.”

Their numbers rapidly declined, and by 1950 the northern population had disappeared.

“This just left the southern population based around the Empty Quarter, southeast Saudi Arabia and the border of the UAE and Oman. Then by the 1960s, it went down and down and down,” Mallon said.

“This just left the southern population based around the Empty Quarter, southeast Saudi Arabia and the border of the UAE and Oman. Then by the 1960s, it went down and down and down,” Mallon said.

Operation Oryx, which included the World Wildlife Fund and Phoenix Zoo in the US, was set up to establish a herd in captivity to prepare to reintroduce them into the wild.

“They caught a few of them from the southern population in Yemen on the border with Oman and took them back to London Zoo. Then there were a couple donated from the ruler of Saudi Arabia at the time, and they were taken to Phoenix Zoo in Arizona, which has a similar desert climate, and they built up this world herd,” Mallon said, adding that this provided hope for the desert animal.

The first reintroduction of 10 animals was in 1982 at the Omani Central Desert and Coastal Hills in the Arabian Oryx Sanctuary.

It was subsequently extended to Saudi Arabia at the Mahazat Al-Sayd Protected Area.

Releases in this fenced area began in 1990.

In 1995, a secondary release site was established in Uruq Bani Ma’arid in the southern part of the Kingdom.

In 1997, said Mallon, oryx were released in three sites in northern Israel, and were introduced to the UAE a few years later in the oryx reserve in Abu Dhabi.

Other sites have since been established, and reintroductions in “semi-captive” sites — vast fenced areas to protect them from poachers — have also been made in Jordan and Bahrain, while reintroductions in Kuwait, Iraq and Syria have been proposed, according to the IUCN.

Successful population growth and releases, in addition to the estimated millions of dollars being spent across the Gulf annually on conservation, have driven the population numbers to current levels.

Mallon said it is a major feat to have brought the Arabian oryx back from the brink of extinction, and one that the IUCN hopes will be repeated for other threatened species.

“The Arabian oryx was ‘extinct’ on the Red List, then they became ‘critically endangered.’ Once the population increased they moved to ‘endangered,’ and then moved to a level where they could be called ‘vulnerable.’ It’s a really good conservation story. The next target they have to get to is ‘near-threatened,’ and that’s not far off,” he added.

The IUCN formally categorizes numbers of a species that are at reproductive age.

“We only count the mature individuals, so we don’t count the young ones. We have about 1,220 now, including the young ones, and we’d say about 850 are mature,” Mallon said.

“For the oryx to move to the ‘near-threatened’ category, we’d need to get figures to about 1,400 of these animals, so about half as many again. Considering where we were and where we are now, this is an achievable feat.”

The main populations of the species today are in Saudi Arabia, where there are about 600 in the wild, and the UAE, where there are more than 400 by official numbers, although Mallon said there may be significantly more.

Many more are in semi-captivity.

There are about 110 in the wild in Israel.

Despite a promising start in Oman, few of the species remain in the country due to poaching.

The IUCN estimates that there are just 10 left in the wild in Oman, with a couple of hundred more in semi-captivity.

Mallon said there are few conservation stories as successful as the Arabian oryx, and it was the foresight of Saudi and Emirati rulers, and bodies that established large breeding sites across the Arab world, that have saved the animal from extinction.

Coordination between the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries — such as the General Secretariat for the Conservation of the Arabian Oryx, which was established in 2001 as a landmark regional initiative aimed at coordinating and unifying conservation efforts in the Arabian Peninsula — has also helped.

“This helps to vary the genetics as much as possible, and ensures the longevity of the species,” said Mallon.

“There has been a huge amount of genetic sampling of all the herds to establish which ones are the most diverse. They’re genetically well-managed, and the animals are very carefully looked after.”

Conservation of endangered animals is a growing trend in the Kingdom. In the study “Conservation in Saudi Arabia: Moving from Strategy to Practice,” published in the Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences in 2018, authors noted that there are “marked conservation successes” in the Kingdom of not only the Arabian oryx, but two other endangered species: The sand gazelle and the Arabian gazelle.

The report added that the Saudi Wildlife Authority, established in 1986, has introduced several measures, with more on the way, to deter poachers and other factors that negatively affect populations of endangered species.

But Mallon said challenges for the Arabian oryx remain: “What’s needed is to continue with the captive breeding efforts to continue breeding animals, to continue the existing reintroduction sites and maintaining regional efforts and collaboration across the Arabian Peninsula. This is vital to maximize genetic diversity and reduce the risk of inbreeding.”

He added: “A massive Arabia Peninsula-wide education program on not shooting and hunting, and confiscation of weapons and a massive license system, would also help.”

Mallon said: “Without conservation, these species probably wouldn’t survive. Yet the Arabian oryx is an important part of Arabian biodiversity. It’s the one animal that’s adapted to hyper-arid deserts.”

He added: “It’s an exemplar to a species that has adapted to these conditions, which will be very useful in the future in terms of climate change. It also has its natural role, and serves as a flagship for the desert ecosystem, and also has huge cultural value. So it’s almost the duty of people to preserve it.”

Mallon said efforts thus far deserve worldwide commendation.

“It has been a huge conservation success story of its time. At the time, it was an absolute flagship project. It was a real exemplar of what can be done,” he added.

“A crucial part of conservation success stories is to have government support, funding and long-term commitment. That’s what we’ve seen in Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the wider GCC.”