DUBAI: Nostalgia takes many forms. For the Syrian visual artist Sara Naim, those forms are jasmine, soil and Aleppo soap.

All three are central to her second solo exhibition at The Third Line in Dubai, “Building Blocks” — which runs until February 27 — but not in the way you’d expect.

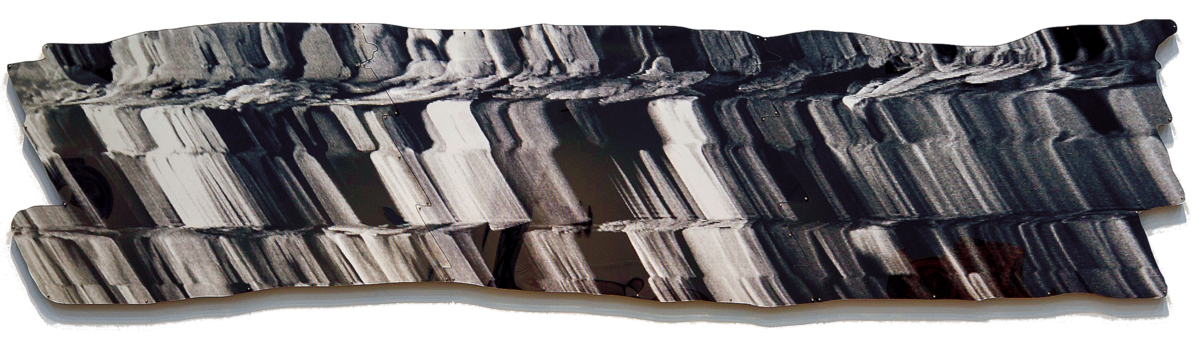

Using a scanning electron microscope, Naim has captured the cellular structure of all three substances, magnified them, and mounted the resultant imagery on wood and plexiglass. She has also deliberately included glitches — formal distortions and light leaks — producing imagery so abstracted it is no longer recognizable. These abstract examinations create the wall works of the show and hint at the imperfection of memory, while in the midst of it all are a series of structures made from 4,000 bars of Aleppo soap.

“I think the idea of warping something that’s familiar into something foreign allows you to shift the viewer’s perspective and to reshape how they think of nostalgia,” says Naim, who was born in London, raised in Dubai, and currently lives in Paris. “Because nostalgia operates in a way that’s no longer linked to the original information. The memory of something changes the more time has elapsed and the more you think about it. You can also become consumed in thought and therefore lost in it.

“You assume that the closer you come to something the more familiar it becomes, but actually you become more distant because it’s so abstracted. For example, some of these are looked at 50,000 times magnified, and at that scale you’re further from its truth.”

In many ways “Building Blocks” is as much about identity as it is about nostalgia. All three of the elements used by Naim may be familiar to her — the jasmine and soil are from her grandmother’s garden in Damascus — but the memories they trigger (through smell primarily) are also perceived as foreign. This is due to her international upbringing as much as it is to the conflict in Syria, which has kept her away from the country for the past eight years.

“I’ve always said I’m Syrian,” she says. “I don’t feel like I’m British, I don’t feel like I’m from Dubai. My blood is Syrian. I completely connect with the land and the people even though there’s an interesting acceptance issue in Syria. Because they don’t consider me to be Syrian really when I’m there and even if I meet a Syrian here or elsewhere they feel disconnected from me. And (vice-versa).

“I met a British woman recently who has a house in Damascus and she’s been going there for the past 20 years. She was telling me about the street that she lives on and where she goes and I didn’t even know those places. And it was such a shame for me to feel like I’m more removed from my country than an expat is. But it’s all the nature of circumstance.”

The exhibition is, in essence, a continuation of Naim’s wider body of work, which utilizes the transmission electronic microscope and the scanning electron microscope to create ‘abstract quasi-photographic imagery’. It’s a practice she says “dissects how proportion shapes our perception and notion of boundary.”

She exists in a world far beyond the realm of classical photography and is often considered a visual artist rather than a photographer. It’s a point of classification that she herself has debated.

“I used to correct people when they introduced me as a photographer, hoping that ‘visual artist’ would give me more freedom,” she admits. “But actually embracing it as photographic allows me to enter into the very dialogue I want to be a part of. Why are cameras made with a rectangular frame? Why are prints framed the way they are? Why is photography considered two-dimensional when it fundamentally uses space and time? I have rid myself of those restrictions, but my work is still photographic.”

Naim is in the final stages of preparing for the exhibition when we meet. The soap has yet to arrive, the towers have yet to be built, but everything else appears to be in place. Although she looks tired, occasionally passing her hand through her hair, she is chatty and affable.

“The names that I’ve given these are not the final names,” she says as we meander through the space. “So, this is ‘Form Six,’ but in my mind — before I named them — it was just ‘Color.’ This was ‘Flower,’ this was ‘Diptych,’ this is ‘Bed Sheet,’ this was ‘Horizontal,’ this was ‘Squiggly,’” she says with a laugh. “Unfortunately I couldn’t keep it like that. ‘Bed Sheet’ wasn’t really flying with the gallery either.”

Far from being universal in shape, each form imitates a topography that Naim has encountered during her scanning process. A process that, in one way or another, Naim has been deeply involved with for the past 10 years.

Initially, it wasn’t so much the scanning electron microscope, or even photography, that Naim was interested in, but the idea of ‘false lines.’

“The skin seems as though it separates the body from its internal anatomy and external world, but — in fact — it’s almost like a collision of two energy forces, and on a cellular scale there is no such division,” she explains. “And how you represent that lack of border or boundary is by going down to the cell and having them look like something foreign — like a foreign landscape, or something macro.”

It is this notion of the non-boundary, the interconnectedness of matter, that drives Naim’s work.

“I like to play with the viewer’s perspective in terms of scale, subject matter and form, but everything must be precise and sterile in order to actually convince someone to shift the way they see or think. A good dancer makes the choreography feel effortless; I try to use that concept in my work,” she says. “If the viewer begins by asking me about the process of how they were built, then that’s my fault. I’ve lost them to rationality rather than abstraction.”