KARACHI: Shehzeen Rashid sat on the stage at her home in downtown Karachi wearing a pale gold dress sprinkled with iridescent diamantes, her hands covered in paisley patterns of henna, and sparkling bracelets adorning her wrists.

As she giggled and fidgeted nervously with the tiny tikka falling over her forehead, women climbed onto the stage one by one, some kissing her face, others putting garlands around her neck but each one leaving an envelope of money or a gift-wrapped box on the table before her. Many of the guests just wanted to have a picture taken.

Shabana Rashid, the mother of Shehzeen Rashid, puts a garland around her ten-year-old daughter’s neck at an event to celebrate her Roza Kushai, or first ever fast, in Karachi on May 19, 2019. (AN photo)

This scene from last Sunday is not from Shehzeen’s birthday party; neither is she getting married. She’s ten years old and her parents have called more than 200 relatives, friends, and neighbors over to celebrate her ‘Roza Kushai,’ or first ever fast.

Muslims around the world, obligated to fast throughout the holy month of Ramadan, abstain from food and even water between suhoor (the meal at dawn) and iftar (the meal at dusk). The ailing, elderly, pregnant women and young children are usually exempt.

But when children do keep their first fast, usually between the ages of seven and ten, it is seen as a rite of passage into the grown-up world of discipline and self-control and celebrated across the community with special meals, gifts for the fasting child and alms for the poor.

Shehzeen’s Qur’an teacher looks on as the ten-year-old reads verses of the holy book at an event to celebrate her Roza Kushai, or first ever fast, in Karachi on May 19, 2019. (AN photo)

In Karachi, Roza Kushai is celebrated most fervently by MoHajjirs, a mostly Urdu-speaking community that migrated to Pakistan when India was partitioned in 1947 after independence from British colonizers.

“I am really happy, I will always remember this beautiful day,” Shehzeen, who studies in the sixth grade, told Arab News minutes before breaking her first ever fast.

As she said a prayer and ate Ajwa dates, an expensive Saudi variety, she declared proudly: “I didn’t even feel thirsty or hungry all day.”

To ensure this, Shehzeen’s mother Shabana Rashid had prepared chicken curry, a yogurt milk drink of lassi, fluffy paratha bread and tea for her daughter’s suhoor. “But she only ate the paratha, which is her favorite, with yogurt,” Shabana said.

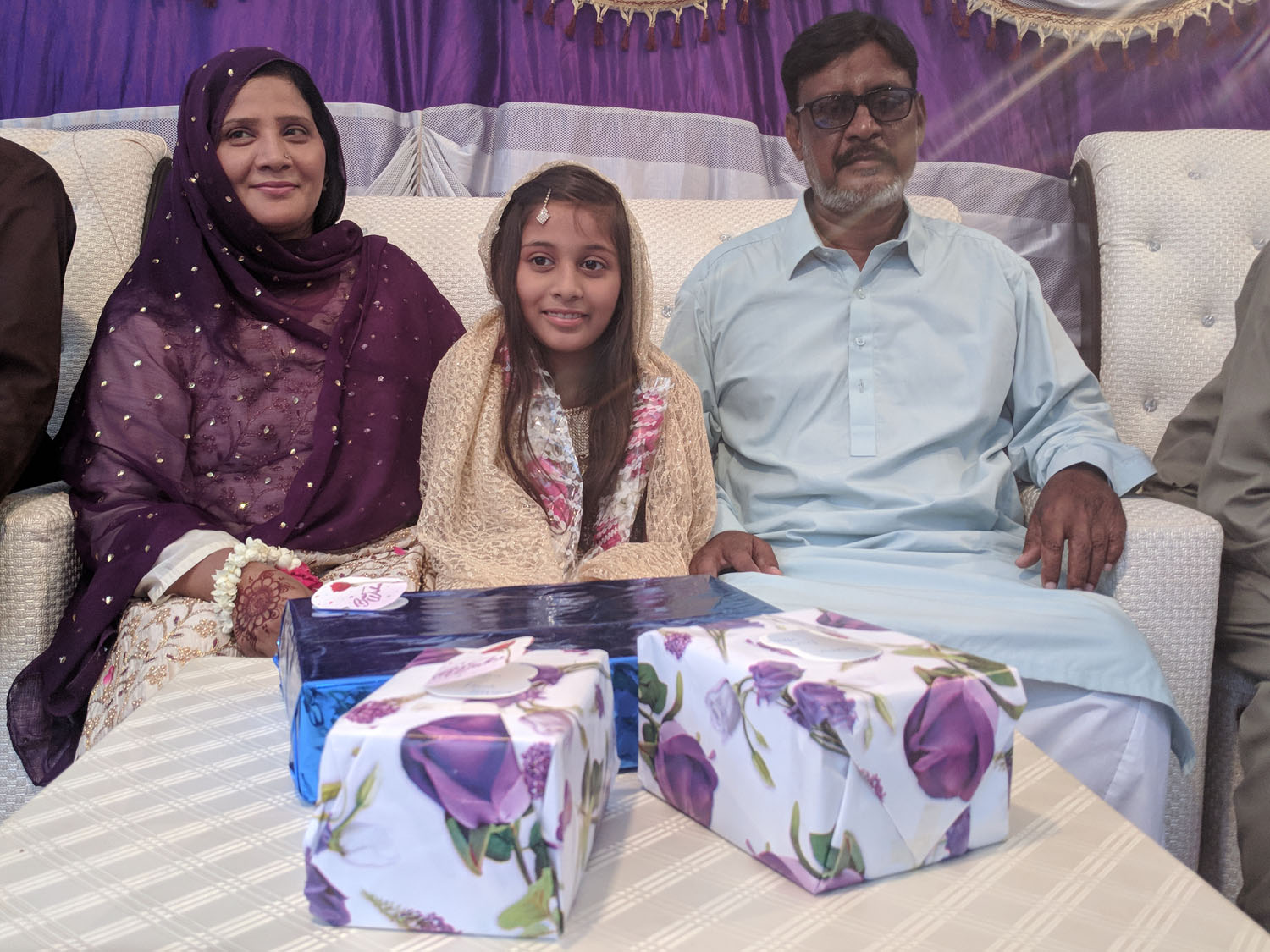

Shehzeen Rashid with her father Muhammad Rashid and mother Shabana Rashid at an event to celebrate her Roza Kushai, or first ever fast, in Karachi on May 19, 2019. (AN photo)

“I was a bit worried that she may feel thirsty and hungry through the day but she showed patience and never complained,” said the proud mother, adding that she was impressed Shehzeen had powered through her first fast despite Karachi’s humid, sticky summer heat made worse by frequent power cuts.

In Pakistan, and across the Muslim world, it is up parents to decide when a child has become mature enough to fast, which is usually after the age of ten or twelve. When youngsters insist on fasting too young, parents try to find a compromise to help them feel they are part of a communal activity without draining them completely: they can, for instance, fast by skipping lunch or just abstain from water all day or forgo food from sunrise only until noon. After ten, most parents will allow their children to fast and some will have a significant celebration for the first fast.

Chicken korma curry, biryani rice, and custard are on the menu at an event to celebrate the Roza Kushai, or first ever fast, of Shehzeen Rashid in Karachi on May 19, 2019. (AN photo)

“We never ask a child to keep a fast, is it is not obligatory upon them,” Shahzeen’s father Muhammad Rashid said. “A date [of Roza Kushai] is finalized only once the child has insisted for long and hard that they want to fast.”

He said his own parents, who hailed from the town of Allahabad in India, had arranged similar celebrations when he and his brother kept their first fasts.

“Our religion is not about forcing a child to fast so we try to make it a celebration for our children,” Rashid said. “The idea is to make children happy and bring them close to Allah.”

Shahzeen has had a busy few days preparing for her big day, picking everything “from her wardrobe, bangles and the design of henna to the menu” herself, her mother said.

“Everything was Shehzeen’s choice,” Shabana said, explaining that children were allowed the responsibility of making all the decisions surrounding their Roza Kushai to help them understand the importance of the obligation of fasting, which is one of the five pillars of Islam.

Muhammad Rashid says he invited around 200 relatives, friends and neighbors at an event to celebrate the Roza Kushai, or first ever fast, of his daughter Shehzeen Rashid in Karachi on May 19, 2019. (AN photo)

“I know that all this is for my first fast only,” Shehzeen said, pointing toward her gifts and the streamers and lights set up on the stage on which she sat. “This won’t happen for every Roza [fast] but I’m still planning to continue fasting until the end of Ramadan.”

Then someone placed a Qur’an in front of Shehzeen and she began to read verses out loud, rocking back and forth as she traced the Arabic lettering with her henna-stained hands as her Qur’an teacher interrupted now and then to fix her pronunciation and her mother and aunts fussed over her, tucking wisps of her hair back into the gold scarf covering the little girl’s head.