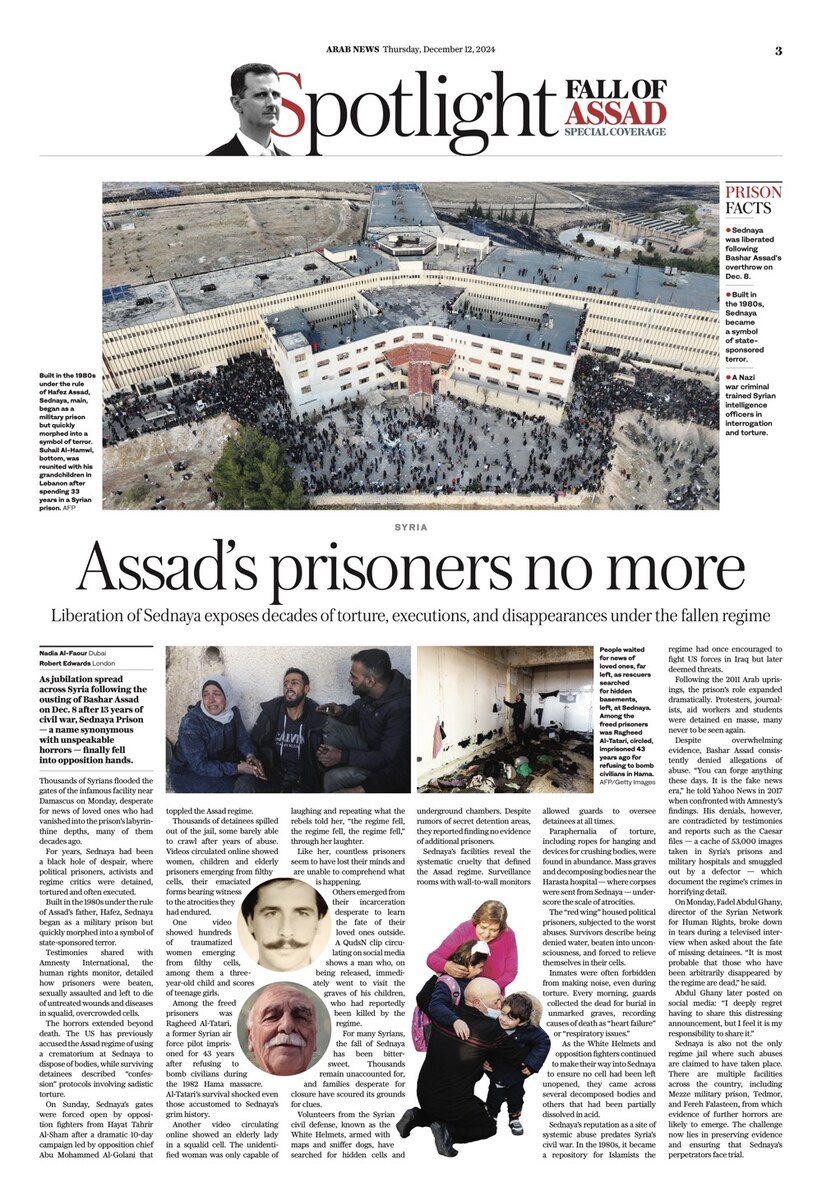

DUBAI/LONDON: As jubilation spread across Syria following the overthrow of Bashar Assad on Dec. 8 after 13 years of civil war, Sednaya prison — a name synonymous with unspeakable horrors — finally fell into opposition hands.

Thousands of Syrians flooded the gates of the infamous facility near Damascus on Monday, desperate for news of loved ones who had vanished into the prison’s labyrinthine depths, many of them decades ago.

For years, Sednaya had been a black hole of despair, where political prisoners, activists and regime critics were detained, tortured and often executed.

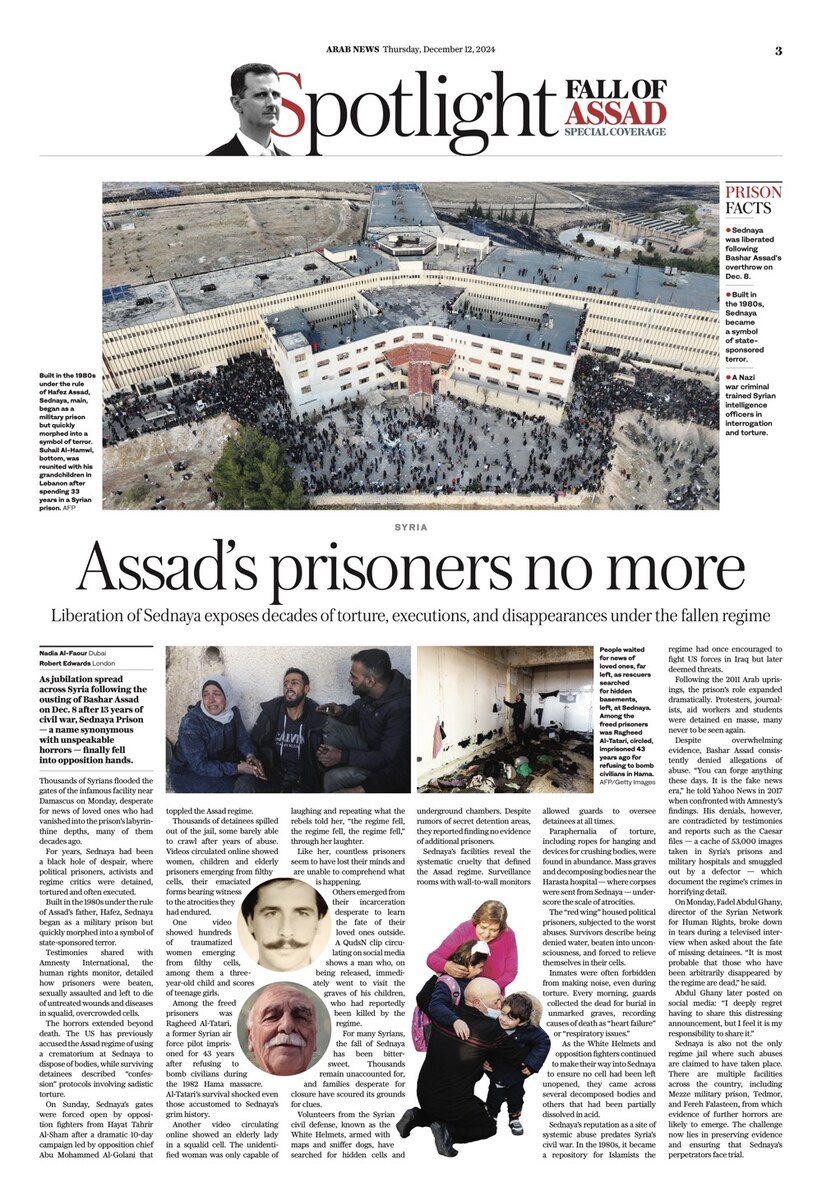

Built in the 1980s under the rule of Assad’s father, Hafez, Sednaya began as a military prison but quickly morphed into a symbol of state terror.

Human rights groups have described it as a “human slaughterhouse,” a moniker reflecting the industrial-scale torture and execution that defined its operations.

Former detainees recount harrowing tales of abuse within its walls. Testimonies shared with Amnesty International, the rights monitor, detailed how prisoners were beaten, sexually assaulted and left to die of untreated wounds and diseases in squalid, overcrowded cells.

Others faced mass hangings after sham trials that lasted only minutes. Between 2011 and 2015, Amnesty estimates that up to 13,000 people were executed. The methods of torture were both medieval and methodical, including beatings, stabbings, electric shocks and starvation.

The horrors extended beyond death. The US has previously accused the Assad regime of using a crematorium at Sednaya to dispose of bodies, while surviving detainees described “confession” protocols involving sadistic torture.

On Sunday, Sednaya’s gates were forced open by opposition fighters from Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham after a 10-day campaign led by opposition chief Abu Mohammed Al-Golani that toppled the Assad regime.

Thousands of detainees spilled out of the jail, some barely able to crawl after years of abuse. Videos circulated online showed women, children and elderly prisoners emerging from filthy cells, their emaciated forms bearing witness to the atrocities they had endured.

One video showed hundreds of traumatized women emerging from filthy cells, among them a three-year-old child and scores of teenage girls.

Among the freed prisoners was Ragheed Al-Tatari, a former Syrian air force pilot imprisoned for 43 years after refusing to bomb civilians during the 1982 Hama massacre. Al-Tatari’s survival shocked even those accustomed to Sednaya’s grim history.

Another video circulating online showed an elderly lady in a squalid cell. The unidentified woman was only capable of laughing and repeating what the rebels told her, “the regime fell, the regime fell, the regime fell,” through her laughter.

Like her, countless prisoners seem to have lost their minds and are unable to comprehend what is happening.

Others emerged from their incarceration desperate to learn the fate of their loved ones outside. A QudsN clip circulating on social media shows a man who, on being released, immediately went to visit the graves of his children, who had reportedly been killed by the regime.

Tragically, not all inmates survived long enough to see liberation.

The decomposing body of activist Mazen Hamadeh, who had traveled the world detailing the horrors he had endured during a previous stint in the regime’s dungeons before being lured back to Syria in 2021 under false promises of security, was found inside.

He bore signs of recent blunt-force trauma.

For many Syrians, the fall of Sednaya has been bittersweet. Thousands remain unaccounted for, and families desperate for closure have scoured its grounds for clues.

Volunteers from the Syrian civil defense, known as the White Helmets, armed with maps and sniffer dogs, have searched for hidden cells and underground chambers. Despite rumors of secret detention areas, they reported finding no evidence of additional prisoners.

Sednaya’s facilities reveal the systematic cruelty that defined the Assad regime. Surveillance rooms with wall-to-wall monitors allowed guards to oversee detainees at all times.

Paraphernalia of torture, including ropes for hanging and devices for crushing bodies, were found in abundance. Mass graves and decomposing bodies near the Harasta hospital — where corpses were sent from Sednaya — underscore the scale of atrocities.

The “red wing” housed political prisoners, subjected to the worst abuses. Survivors describe being denied water, beaten into unconsciousness, and forced to relieve themselves in their cells.

Inmates were often forbidden from making noise, even during torture. Every morning, guards collected the dead for burial in unmarked graves, recording causes of death as “heart failure” or “respiratory issues.”

As the White Helmets and opposition fighters continued to make their way into Sednaya to ensure no cell had been left unopened, they came across several decomposed bodies and others that had been partially dissolved in acid.

Sednaya’s reputation as a site of systemic abuse predates Syria’s civil war. In the 1980s, it became a repository for Islamists the regime had once encouraged to fight US forces in Iraq but later deemed threats.

Following the 2011 Arab uprisings, the prison’s role expanded dramatically. Protesters, journalists, aid workers and students were detained en masse, many never to be seen again.

The prison’s practices bear the fingerprints of Alois Brunner, a Nazi war criminal who trained Syrian intelligence officers in interrogation and torture techniques.

Once a high-ranking Gestapo officer who oversaw the deportation of more than 128,000 Jews to death camps during the Second World War, Austrian-born Brunner was on the run until he was offered protection by Hafez Assad.

Assad refused on multiple occasions to extradite Brunner to stand trial in Austria and Germany in the 1980s, but later came to see him as a burden and an embarrassment to his rule.

In the mid-1990s, Hafez ordered Brunner’s “indefinite” imprisonment in the same squalor and misery the former Nazi officer had taught Syrian jailors to inflict on their prisoners. He died in Damascus in 2001 aged 89.

Despite overwhelming evidence, Bashar Assad consistently denied allegations of abuse. “You can forge anything these days. It is the fake news era,” he told Yahoo News in 2017 when confronted with Amnesty’s findings.

His denials, however, are contradicted by testimonies and reports such as the Caesar files — a cache of 53,000 images taken in Syria’s prisons and military hospitals and smuggled out by a defector — which document the regime’s crimes in horrifying detail.

On Monday, Fadel Abdul Ghany, director of the Syrian Network for Human Rights, broke down in tears during a televised interview when asked about the fate of missing detainees. “It is most probable that those who have been arbitrarily disappeared by the regime are dead,” he said.

Opinion

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in (Opinion field)

Abdul Ghany later posted on social media: “I deeply regret having to share this distressing announcement, but I feel it is my responsibility to share it.”

Syrian activist Wafa Ali Mustafa, whose father was forcibly disappeared in 2013, said on X that she has been searching “through harrowing videos, clinging to any chance” that he might be among the survivors.

The prison’s fall has prompted calls for accountability. “The blood that was spilled here cannot just run. They must be held to account,” Radwan Eid, a former detainee, told Reuters news agency.

Sednaya is also not the only regime jail where such abuses are claimed to have taken place. There are multiple facilities across the country, including Mezzeh military prison, Tedmor, and Fereh Falasteen, from which evidence of further horrors are likely to emerge.

The challenge now lies in preserving evidence and ensuring that Sednaya’s perpetrators face trial.

The International Committee of the Red Cross and other organizations have urged the armed opposition to protect records and prevent further destruction. However, looting and chaos at Sednaya has complicated these efforts.

As Bashar Assad and his acolytes have been granted asylum in Russia, it seems unlikely the deposed president and others in the upper echelons of his regime will stand trial for their role in the crimes perpetrated at Sednaya.

While the road to justice may be long, Sednaya’s liberation represents a turning point. For survivors and families, it offers a rare opportunity to confront the truth and honor the memories of those lost.

The dismantling of Sednaya’s imprisonment machinery is a symbolic step toward rebuilding the nation and serves as a reminder of the resilience of those who survived, and the enduring need for accountability.