WASHINGTON: That Joe Biden, the man picked by America’s first black president as his number two, should now be suffering attacks over his record on race might seem surprising.

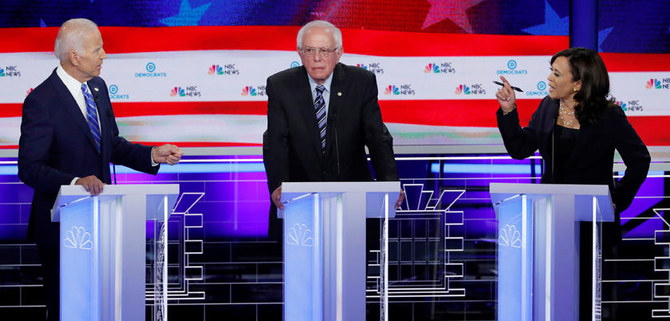

But that is exactly what happened after the former vice president’s televised debate Thursday with nine other Democratic presidential hopefuls.

And now the question for Barack Obama’s deputy — up to now the clear leader in national polls — is whether his positions on race from nearly a half-century ago will continue to haunt his campaign.

Here are some key points:

Senator Kamala Harris, the only black woman in the Democratic presidential field, forcefully questioned Biden on his opposition in the 1970s to court-ordered busing programs aimed at integrating public schools.

“I do not believe you are a racist,” she said, before demanding that Biden explain why he worked with two known segregationists in the Senate “to oppose busing.”

Harris noted, in a quavering voice, that as “a little girl in California” she was “part of the second class to integrate her public schools” in a busing program. Without it, she said, she might not be a senator today.

Biden called her remarks “a mischaracterization of my position across the board.”

“What I opposed is busing ordered by the (federal) Department of Education.”

But Harris replied that because many states failed to desegregate schools, it fell to the federal government to do so.

What happened then

In the 1970s, Americans fiercely debated the need for school busing as a remedy to long-segregated public schools. Because the schools are mostly funded by local property taxes, those in poorer areas tend to have worse facilities and lower-paid teachers.

Court-ordered busing programs for some districts — sending black students from low-income areas to predominately white schools in wealthier areas, and vice versa — sparked explosive resistance, mostly from white parents who demanded that their kids remain in neighborhood schools.

Riots broke out. But black parents and civil rights groups said there was no other way to make schooling more equitable.

Since then, court rulings, legal developments and demographic shifts have weakened or ended busing programs, and resegregation of schools has increased dramatically.

'Asinine policy'

While campaigning for the Senate in 1972, a young Joe Biden called for racial equality and criticized anti-busing leaders.

But amid intense opposition to busing in his home state of Delaware, he came to argue that while busing might make sense in cases of historic “de jure segregation” — that is, segregation sanctioned by law as in the Deep South — it was an inappropriate remedy for the “de facto segregation” that existed in many Northern cities.

He eventually became an advocate for anti-busing legislation. Busing was “a bankrupt concept” and “an asinine policy,” he said, and it was “profoundly racist” to suggest that black students could succeed only if sitting next to whites.

Damage control

Biden's campaign aides scrambled to lessen the damage, declaring Harris’s comments a “low blow” and insisting Biden is a fervent defender of civil rights.

“I know I’ve fought my hardest to ensure voting rights, civil rights, are enforced everywhere,” he told a largely black group in Chicago on Friday.

Jason Sokol, a University of New Hampshire professor who specializes in race and politics, told AFP that Biden was “disingenuous and misleading” in the debate, adding, “I’m surprised that he didn’t admit that he was wrong, and then go on to tout his own record on civil rights. This was his big mistake.”

“He can’t get past his own anti-busing history if he doesn’t confront it and explain whether he believes he was right or wrong,” Sokol said.

“As long as he tries to dodge the issue or sidestep it, it will continue to haunt him.”

But other analysts pointed out that for many African-American voters — a key bloc in Democratic politics — the most important thing about Biden remained this: that he was, after all, picked as deputy to the nation’s first black president.