LAHORE: Separated by more than 700 km and a hostile international border between them, two towns in India and Pakistan share the same name and a near-identical culture.

Mianwali, near the northwestern tip of Pakistan’s Punjab province and bordering Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, is an ancient district along the banks of the Indus River known for its suji (semolina) halwa, its red hills packed with some of the world’s finest rock salt and currently, its most famous native: Prime Minister Imran Khan.

Its multi-ethnic people, famed for their handsomeness, speak Urdu, Saraiki, (which is a lesser spoken twin of the Punjabi language), and Pushto. The latter is an anomaly in the eastern Punjab province but is spoken in Isakhel, a picturesque Mianwali town that sits like a honeycomb in the hills and is known by its majority clan, the Niazis, who settled here from Afghanistan centuries ago.

The partition of India in 1947 witnessed one of history’s largest mass migrations as millions of Muslims and Hindus crossed the border into India or Pakistan depending on their religion. During this time, Mianwali, which was on the Pakistan side, was hurriedly abandoned by its majority Hindu inhabitants, many of whom eventually settled in the heart of Indian capital New Delhi, where they created their own version of the home they left behind: Mianwali Nagar, now a residential colony of 800 modern homes and over 5,000 residents.

Roshan Lal, who fled Pakistani Mianwali alongside the town’s Hindu inhabitants during the Indian partition, stands at the gates to Mianwali Nagar in New Delhi, a residential colony named after his ancestral hometown, Dec. 15, 2018. (Family photo)

“At Mianwali Nagar, we have kept our language and culture intact. We speak Saraiki language, we wear shalwar kameez, sherwani, turban and khussa (traditional shoes) and we eat same food as we used to while being in (Pakistani) Mianwali,” Roshan Lal, a resident of Mianwali Nagar who fled Pakistan as a child in 1947 alongside his family, told Arab News by telephone.

“We can read and write Urdu as well,” he said, and added that despite being Indian, the pride he takes in his ancestral home was greatly renewed last year when Imran Khan became Prime Minister of Pakistan.

It is a connection to the land that belies the three wars fought between India and Pakistan since the partition, in the backdrop of 70 years of conflict and fractured diplomatic relations.

Roshan Lal with members of his family at Namal Lake during a visit to their ancestral hometown, Mianwali in northwestern Punjab, Pakistan. Dec. 6, 2004. (Family photo)

Rooted in a sense of nostalgia, it was Chaudhary Ghansham Das, a leader of Mianwali’s once-thriving Hindu community, who founded Mianwali Nagar in Delhi during the 1950s. A committee, led by him and comprising Mianwali’s Hindu migrants, acquired a large piece of land which later served as the colony as it now stands, an ode to the ancestral Pakistani town they had fled.

“We all came here empty-handed, left all our belongings behind with tears in our eyes and had to make a new beginning again,” Lal said, and added there were thousands of other Hindu migrants from Mianwali who had come to India and settled in other areas.

Har Bhagwan Sapra, a retired officer of Indian Railways who also fled Mianwali as a child, said that Mianwali Nagar was a tribute to where they came from, and the colony’s residents were always proud to see their ancestral hometown in the news.

“We are really happy and excited to see our homeland developing into a modern city, and it’s a matter of great pride that Mianwali houses the world-class Namal University,” Sapra told Arab News by telephone from India.

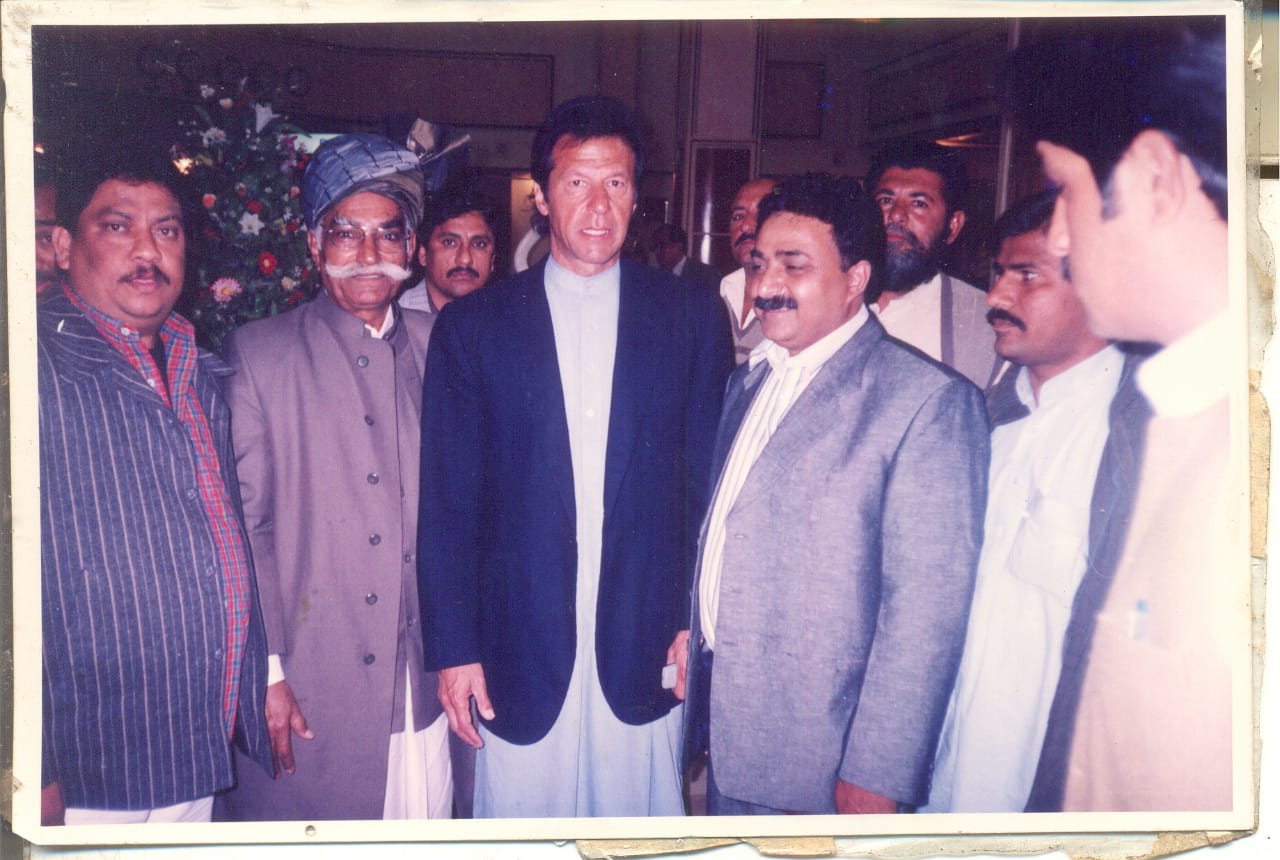

Roshan Lal, who fled Mianwali during the Indian partition, poses for a photograph with Imran Khan at a wedding in Islamabad on Jan. 26, 2006. (Family photo)

“When Imran Khan led Pakistan cricket team’s tour to India in the late ’70s and ’80s, we cheered for both teams,” he said.

According to Hafeezullah Niazi, a brother-in-law of Prime Minister Khan and a well-known resident of Mianwali, the Hindus fleeing during the partition left all their belongings, their gold and other precious items behind. It was this lack of closure, an “emotional attachment to their ancestral land” that led them to establish Mianwali Nagar in India, in remembrance of Mianwali in Pakistan with its language and culture intact.

“I get nostalgic whenever I go to Mianwali Nagar during my India visits,” Niazi said. “Our hosts give us immense respect and honor. They open their doors, spare special rooms, provide prayer mats, serve ... food and care about smallest of needs of their guests from Mianwali.”

The love it seems, is entirely mutual.

A former resident of Pakistan's Mianwali district, Roshan Lal now lives in a New Delhi colony of former migrants, and still follows the culture of his ancestral hometown. Here, he dances dressed in the traditional shalwar kameez, at a family event at his home in Mianwali Nagar in Delhi, Jan. 14, 2019. (Family photo)

“I have visited Pakistan more than two dozen times,” Roshan Lal said. “We get...love and warmth from the people every time we visit Mianwali,” he said, and added, “We attend each other’s marriages and share the sorrows as well.”

Though Hafeezullah Niazi is a vocal critic of Imran Khan and his party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, he conceded that Mianwali’s old inhabitants in India were excited about Khan winning the election last year.

“They take great pride in it,” he said, and added that the people of Mianwali Nagar saw Khan as an ambassador of peace due to his stance on stabilizing relations between the two nuclear-armed neighbors.

But peace, he said, had few real takers in regional politics with India’s newly re-elected rightwing Prime Minister Narendra Modi coming to power on the back of an election campaign largely rooted in an anti-Pakistan stance.

“India is neither issuing visas to Pakistanis nor allowing Sikh pilgrims to visit Pakistan,” he said.

Still, it would seem that despite Delhi’s bitter overtures toward Pakistan, there remains at least one colony in the heart of India’s capital whose people continue to yearn for the river town they left behind long ago.