DUBAI: “We set out again at night from this blessed valley (called Marr), with hearts full of gladness at reaching the goal of their hopes, rejoicing in their present condition and future state, and arrived in the morning at the City of Surety, Makkah (God Most High ennoble her),” wrote the traveller Ibn Battuta in 1326. He had set out from Morocco the previous year, journeyed across North Africa to Cairo, before heading to Jerusalem and Damascus and then on to Medina and Makkah.

Ibn Battuta spent four days in Medina before reaching Makkah, where he donned a simple white ihram and immersed himself in the rituals of the Hajj. At the Kaaba, “we made around it the (seven-fold) circuit of arrival and kissed the holy Stone; we performed a prayer of two bowings at the Maqam Ibrahim and clung to the curtains of the Kaaba at the Multazam between the door and the Black Stone, where prayer is answered; we drank of the water of Zamzam…; then, having run between al-Safa and al-Marwa, we took up our lodging there in a house near the Gate of Ibrahim.”

The Moroccan explorer provides a fascinating depiction of the fifth pillar of Islam from almost 700 years ago, and he is far from alone when it comes to documenting the wonders of the Hajj. The annual Islamic pilgrimage is a recurrent and varied theme in art, poetry and prose from across the Islamic world, but nowhere more so than in travel literature. From the Andalusian geographer Ibn Jubayr to the Spanish explorer Ali Bey El-Abbassi, the genre is rich with eloquent and descriptive texts, most of which not only bring to life the pilgrimage itself, but the varied times in which they took place.

“There is a rich literature on Hajj,” says Dr Nuha Al-Sha’ar, an associate professor at the American University of Sharjah. “Many documented their Hajj journey and therefore we have a genre of travel literature called ‘Al-Rihla Al-Hijaziyya’ — the journey to Hijjaz to perform pilgrimage. We also have many travel accounts of the Hajj. The famous Ibn Battuta’s journey was first to (document performing) Hajj… and in the modern period the famous Bint Al-Shati documented her journey to Hajj (in) ‘Ard Al-mu’jizat.' Ibrahim al-Mazini also documented his Hajj journey.”

During the first half of the 14th century, the theologian and spiritual writer Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya published “The Journey of Love,” which combined the inner spiritual journey of the Hajj with its many physical challenges. The poem described Al-Jawziyya’s journey, the Kaaba, Arafat, Muzdalifah and Mina, the farewell tawaf, and his fellow pilgrims. “You see them on their mounts, hair dusty and disheveled,” he wrote. “Yet never more content, never happier have they felt/Leaving homelands and families due to holy yearning/Unmoved are they by temptations of returning/ Through plains and valleys, from near and far/Walking and riding, in submission to Allah.”

Of the Kaaba he said: “When they see His House — that magnificent sight/For which the hearts of all creatures are set alight/It seems they’ve never felt tired before/For their discomfort and hardship is no more.”

Although central to the Muslim faith, the Hajj has also drawn writers from further afield. From Europe and the Far East, and even from North America, from where the civil rights campaigner Malcolm X travelled in 1964. It was in Makkah that he discovered an Islam of universal respect and brotherhood.

“There were tens of thousands of pilgrims, from all over the world,” he wrote upon his return. “They were of all colors, from blue-eyed blondes to black-skinned Africans. But we were all participating in the same ritual, displaying a spirit of unity and brotherhood that my experiences in America had led me to believe never could exist between the white and the non-white.”

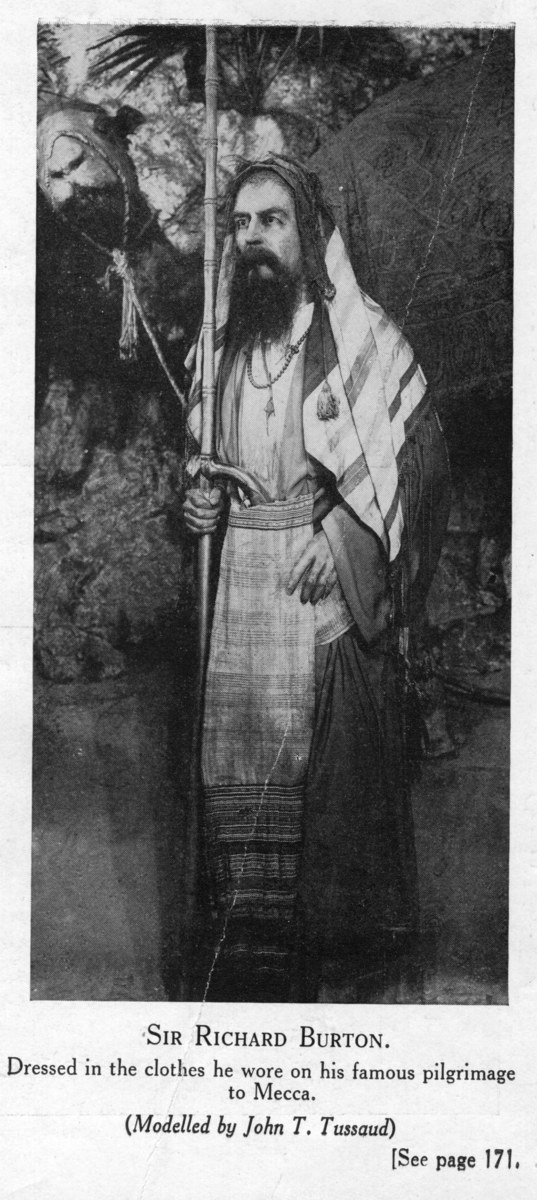

European Western writers also sought to experience the Hajj’s spectacle. The Victorian explorer, geographer and writer Sir Richard Francis Burton published his “Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Mecca” in 1855 after disguising himself as a dervish in order to gain access to Makkah illicitly. Another Briton, Eldon Rutter, visited Makkah and Medina between 1925 and 1926 and published “The Holy Cities of Arabia” in 1928. The book was launched to universal critical acclaim, although Rutter — a convert to Islam — remains an obscure figure.

“Through the forest of columns, I could dimly see the great gravel-strewn quadrangle, over four and a half acres in extent; and in its midst, covered by a black cloth which made it hardly defined in the darkness, stood the Bayt Allah, the House of God — the Ka’ba,” wrote Rutter. “Under the arches of the cloisters, bare-footed, long-robed, silent figures were hurrying to take up their positions behind the imams. In all parts of the great quadrangle, worshippers were forming into long lines facing the Ka’ba, preparing to perform the morning prayer. Over the crest of the hill of Abi Cubays, the first faint light of dawn showed in the sky, like a transparent patch in a sheet of dark-blue glass.”

Although literature provides us with a window through which to observe the Hajj, it is arguably art that is central to its wider understanding. It is, after all, the pillar of Islam that lends itself most readily to artistic expression.

“Hajj is central to the Muslim faith and artists and creatives are no exception to this,” says Uns Kattan, head of learning and research at Art Jameel. “Many artists throughout history, both modern and contemporary, have documented their own journeys of pilgrimage or have studied the coming together and unity of cultures during the sacred act and the introspective manifestations behind the ritual.

“Artists who choose to respond to the experience and idea of Hajj have done so in various mediums and through powerful representation. One can be reminded of contemporary Saudi artist Maha Malluh’s work “The Road to Makkah” contrasting experiences of travelling on Hajj in the past and present, or French artist Kader Attia’s “Black Cube II” painting series inspired by the form of the Kaaba.”

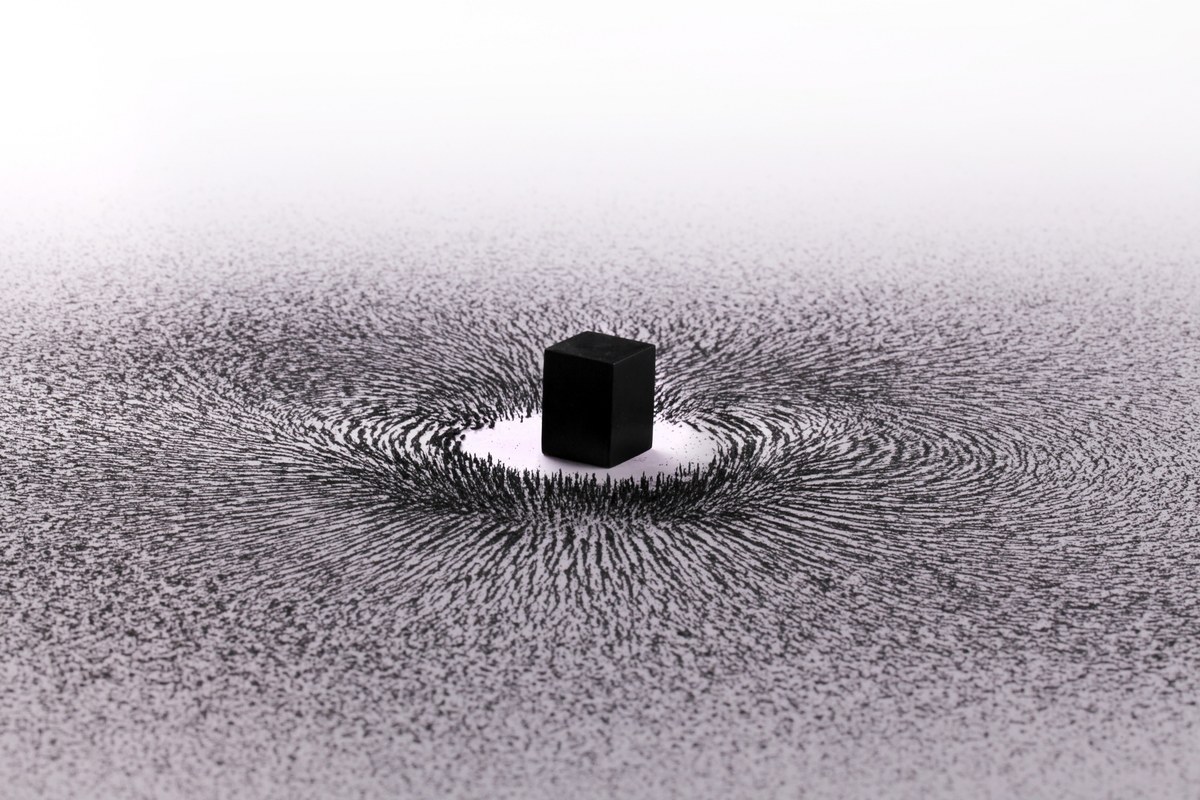

Kattan also cites Saudi artist Ahmed Mater’s “Magnetism,” an installation that depicts a black cubic magnet encircled by steel dust that evokes the tawaf in Makkah. The works of Mater, Malluh and Kader were all part of “Hajj: Journey to the heart of Islam,” an exhibition that took place at the British Museum in 2012.

Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai is currently featuring the work of Pakistani artist Wardha Shabbir, one of eight finalists who took part in the fifth edition of the Jameel Prize for contemporary artists and designers. Her work depicts the Kaaba and tawaf through traditional miniature painting.

Some of the most famous visual depictions of the Hajj, however, are shown from a Western perspective. Leon Belly’s “Pilgrims Going to Mecca” is amongst the most celebrated and is considered a masterpiece of Orientalist painting. Completed in 1861, it is now exhibited at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and portrays a long and compact caravan crossing the desert on its way to Makkah. There is also Ludwig Deutsch’s “The Procession of the Mahmal Through the Streets of Cairo."

It should come as no surprise that the Hajj should feature so prominently in the arts. Writers, painters, poets and musicians tend to be inspired by that which moves them most, so the pilgrimage — which for many will be the defining spiritual experience of their life — is fertile creative ground too.