PESHAWAR: Sana Khan was 18 when she was stabbed to death by her brother, Qasim Ali, in August this year.

Her crime? Ali accused her of bringing shame and dishonor to their family by choosing to play the Rabab – a lute-like instrument and an important element of Pashtun music.

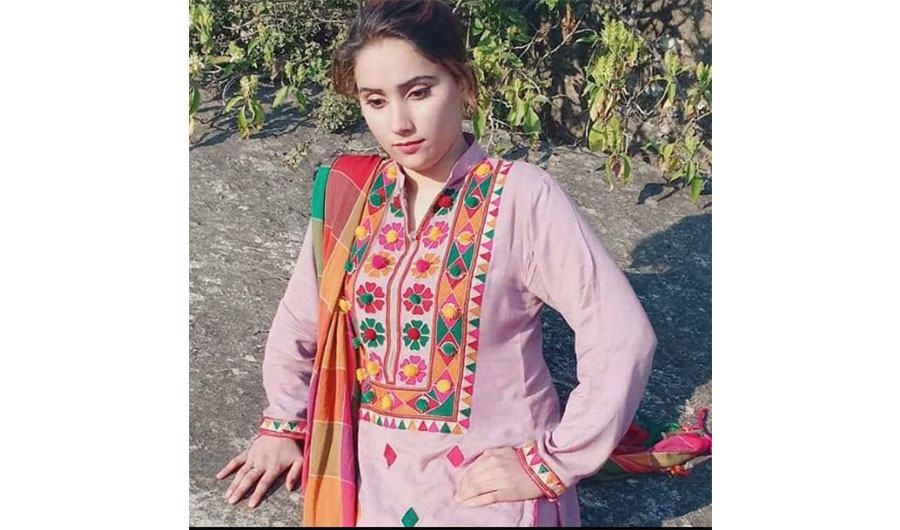

A rare photo of Sana Khan 18, the late Pashto singer, was stabbed to death by her brother in Swat, a scenic valley in northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province in August 2019. (Photo Courtesy singer’s family)

The two hailed from Swat, a scenic valley in the northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province where a number of musicians – primarily women singers – have either been killed or forced to seek asylum abroad after receiving death threats.

Sana’s mother says the murder was three years in the making.

“She was only 15 when she joined the profession. My son had sworn many times that he will not hurt his sister but he stabbed her to death when she came back from a music concert. Perhaps, he was feeling it a disgrace for himself,” Nazo Bibi, their mother told Arab News.

According to data collected by Waqar Ali Shah, a leading Pashto poet who tracks violence against Rabab musicians, at least 16 artists – most of them women – have been killed in the past 10 years, primarily by their relatives in the name of “protecting family honor.”

Bibi says Ali had stepped into Sana’s room late at night before repeatedly stabbing her while she lay asleep. Sana was immediately rushed to a local hospital where she succumbed to her wounds.

District Police Officer (DPO) Sayed Ashfaq Anwar, however, has a conflicting version to the killing, denying reports that it was a case of honor killing and boiling it down to a domestic dispute instead.

Imtiaz Hussain, a renowned Rabab player, opens music academy in Parachinar, the main town in Kurram tribal region, to revive Pashtun music. Hussain (center) plays Rabab at his academy (December 2018). So-called family honor is shrinking space for female artistes in northwestern Pakistan. Photo shared by the musician

Anwar says a case of murder has been registered against the accused and that the police were conducting raids to nab the killer who was still at large.

“The murder of the singer cannot be associated with honor killing rather it was a financial dispute. The accused Qasim Ali demanded money from his sister but she refused, prompting him to take the extreme step. She was herself, complainant of the case,” the police officer told Arab News.

Sana’s case is not the only example of a musician who has been murdered in the area and follows reports of several artistes lodging complaints after being threatened to quit the profession or risk losing their lives.

Dabgari in Peshawar, the provincial capital of KP, and Banrr in Swat are the two famous “music streets” that are also known as the early learning centers for musicians to be trained in the craft.

“Youngsters who want to adopt music as a profession come straight to Dabgari and Banrr because they find professional people there,” Shah said.

Imtiaz Hussain, a renowned Rabab player, opens music academy in Parachinar, the main town in Kurram tribal region, to revive Pashtun music. Hussain (right) plays Rabab at his academy (December 2018). So-called family honor is shrinking space for female artistes in northwestern Pakistan. Photo shared by the musician

Rabab originated in central Afghanistan but gained popularity after musicians from Iran, Turkey, Tajikistan, and Azerbaijan began playing it too.

Known as Afghanistan’s national instrument, the Rabab is deeply popular among the Pashtuns living in northwestern Pakistan where it found favor with young musicians in the valley.

Provincial Cultural Director Ajmad Khan told Arab News that while the killings were worrying and problematic, most women had been murdered by their own relatives, making it difficult to protect musicians receiving threats.

“We don’t have any gadgets to preempt attacks directed against singers by their relatives because they have their domestic problems. What we do is that we have established an endowment fund to facilitate singers having financial problems or facing any serious disease. And we will issue them with health cards,” he said.

Another emerging singer, 30-year-old Rashed Ahmad who is studying for a Ph.D. in Pashto music from the University of Peshawar, told Arab News that most of his community members were living in a vortex of problems amid a severe financial crisis and a sense of insecurity.

He suggested that the provincial government should establish a music industry and devise a long-term strategy to tackle such problems.

“Society needs to be educated on how to deal with artists and vice versa, which will go a long way in countering incidents of violence,” he said, adding that the government should devise a plan to allocate scholarships and quotas for musicians in each and every department, which would help support artistes financially.

Shah says the problem is not new.

Rashed Ahmad, an emerging vocalist, performs at a concert in Peshawar, the main town in northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in April 2019. So-called family honor is shrinking space for female artistes in northwestern Pakistan. Photo shared by the musician

The northwestern province has never been a safe region for artists because many female musicians have been killed by their relatives while male singers have sought asylum in foreign countries.

He cited the example of a female singer, Nazia Iqbal, who left the country in July this year and sought asylum in the UK while male artists such as Haroon Bacha, Sardar Ali Takkar, Gulzar Alam and Alamzeb Mujahid have moved to Prague, Afghanistan, and US respectively.

Earlier this year in May, a renowned singer Meena Khan, 32, was shot dead by her husband in the Banrr area of Swat because she had refused to quit her profession, data from police records showed.

Six years ago, another renowned singer Ghazala Javed was killed by her ex-husband who was sentenced to death for her murder by a court in Swat last year.

In 2009, Ayman Udas, another female vocalist, was gunned down inside her home by her brothers who accused her of breaking tradition and defaming the family.

Last year, stage actor Sumbal Khan was gunned down in Mardan district. According to police, three armed men had broken into Sumbul Khan’s house and shot her dead after she refused to accompany them to perform at an event arranged by the killers.

Similarly, in 2014, artiste Gulnaz alias Muskan was killed in the Gulberg area of Peshawar by unidentified gunmen. Police said gunmen broke into Muskan’s house before shooting her dead.

And while the series of attacks on musicians, particularly women, has created a sense of fear in the province, the sound of Rabab music continues to permeate through the valley.

“The main problem among a majority of Pashtuns is that they love the music but abhor artists because of so-called family honor,” Shah added.