GHIZER, Pakistan: Two years ago, Raja Iqbal Hussain quit his job as a low-paid hotel waiter in Dubai and went back to his native village in northern Pakistan to set himself up as a fish farmer.

The 36-year-old father of three has now started bringing in a small profit from his fish, and is looking forward to earning more next year once they have grown.

Local farmers are increasingly choosing fish over crops, as the climate warms in mountainous Gilgit-Baltistan region.

In Dubai, Iqbal’s monthly wages barely amounted to 50,000 Pakistani rupees ($321).

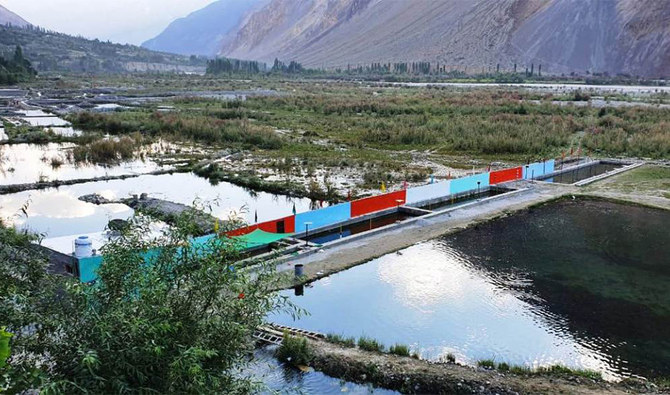

“I earn a much better amount from my business here,” he said of the lake he built next to the river in Birgal village, Ghizer District, some 100 km (62 miles) north of Gilgit city.

The lake contains about 50,000 fish, mainly trout, which Iqbal sells raw for 1,200 rupees per kg and cooked for 1,800 rupees.

He charges 2,000 rupees per kg for fish caught by boat, which visitors can take out on the water.

A recent report from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization said steadily rising temperatures had increased the frequency and intensity of disasters in the region’s valleys, threatening the sustainability of traditional agriculture.

One farmer reported that wheat productivity had declined by almost 50% from 2010-2015 with no sign of improvement, and said heavy rain had ruined his crops, it noted.

According to the report, poverty and hunger are worse in Pakistan’s mountain regions, with about half of households in Gilgit-Baltistan suffering from under-nutrition.

Backed by government support, fish farming is gaining popularity in Ghizer District as a sustainable source of income and nutrition amid the growing effects of climate change.

GLACIAL LAKES

Abdul Wahid Jasra, Pakistan country head for the International Center for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), said that, as temperatures rise, melt-water from glaciers is forming lakes that can be used for cold-water fish farming.

They include Attabad Lake in the Hunza valley, which appeared in 2010 following a deadly landslide.

“Mountain communities have very limited sources of income, and this sector can open multiple avenues for income generation,” Jasra said.

Neighbouring China could become a major export market for fish with investment in factories and transportation, he noted.

“I see huge potential for the mountain farmers for climate change adaptation to increase their livelihood through fish farming,” Jasra added.

Crops commonly grown here — wheat, potatoes and barley – and fruits such as grapes, apples and apricots can be badly damaged by heavy rains, pests and other weather-related diseases.

Fish farming, on the other hand, generates income all year round, and faces minimal risks from climate change, Jasra said.

Ghizer District is popular for trout-breeding and fishing, which can only be done with the permission of the authorities.

ICIMOD and the Pakistan Agricultural Research Council have established a mountain research center in Gilgit and are setting up a laboratory to find out more about local and exotic cold-water fish.

CULTIVATING MARKETS

Iqbal said fish farming was “the best business” for those who have suitable land and a steady water supply.

His customers include local hotels, tourists and individuals. But as trout can easily spoil, he has yet to start supplying trout to major city markets due to a lack of proper packing and transport.

Many other farmers in the area have also constructed fish ponds.

Khursheed Aman in Sundi village, in Ghizer’s Yasin valley, put in two small ponds near his house, containing as many as 5,000 fish.

Besides his job in a government office, he does good trade selling fish to tourists and local households.

“Many people prefer to buy fish rather than consuming chicken even though it is a comparatively expensive commodity,” Aman said.

The government has provided support to set up as many as 60 private fish farms in the last three years and 10 more are under construction, said Fida Alam, assistant director of fisheries with the Gilgit-Baltistan government.

As well as technical and financial help, the government has given 400,000 small fish to farmers this year to help them expand their businesses.

“We are encouraging farmers to switch to this since there is a huge potential in the sector,” Alam said.

In a short space of time, people are taking a keen interest due to attractive returns and less labor and investment than are needed to cultivate traditional crops, he noted.

The local government is considering fixing the price of fish to make it more affordable for ordinary people, he added.

The government is also working to get women involved by establishing small fish ponds in their backyards for consumption at home and small-scale trade.

Community-financed fish farms are being set up too, with the income from selling fish being spent on improving health, education and other shared facilities.

Ali Asghar, a local fisheries department officer, said the federal government had approved a project this year to offer training, expertise and financial assistance to help farmers breed and sell trout in big cities and even internationally.

“We see increasing supply in future, and growers need major markets,” he added.

Farid Ahmad, a fisheries researcher at the Karakoram International University Ghizer Campus, said local people had started tapping into trout fishing at a commercial level.

There was now a need to develop linkages between farmers and big hotels in cities, including Gilgit, Hunza and beyond, to make the activity profitable, he added.

“It is a time-consuming but lucrative business for the farmers,” he added.