KARACHI: As his friends grab a bat and ball to play a round of cricket with other boys in the neighborhood, Siddiq Omar picks up his school bag and heads toward the Jamia Masjid Khyber, an Islamic seminary or madrassa in the Orangi town of Karachi.

This has been his routine on every Friday for the past three weeks, but Omar doesn’t go there for religious studies.

Instead, he’s part of a group of students being trained to read and write in Pashto – an idea initiated by Fazal Khaliq Ghamgeen, an author and poet, who runs his own general store in the same locality that is dominated by Pashtuns.

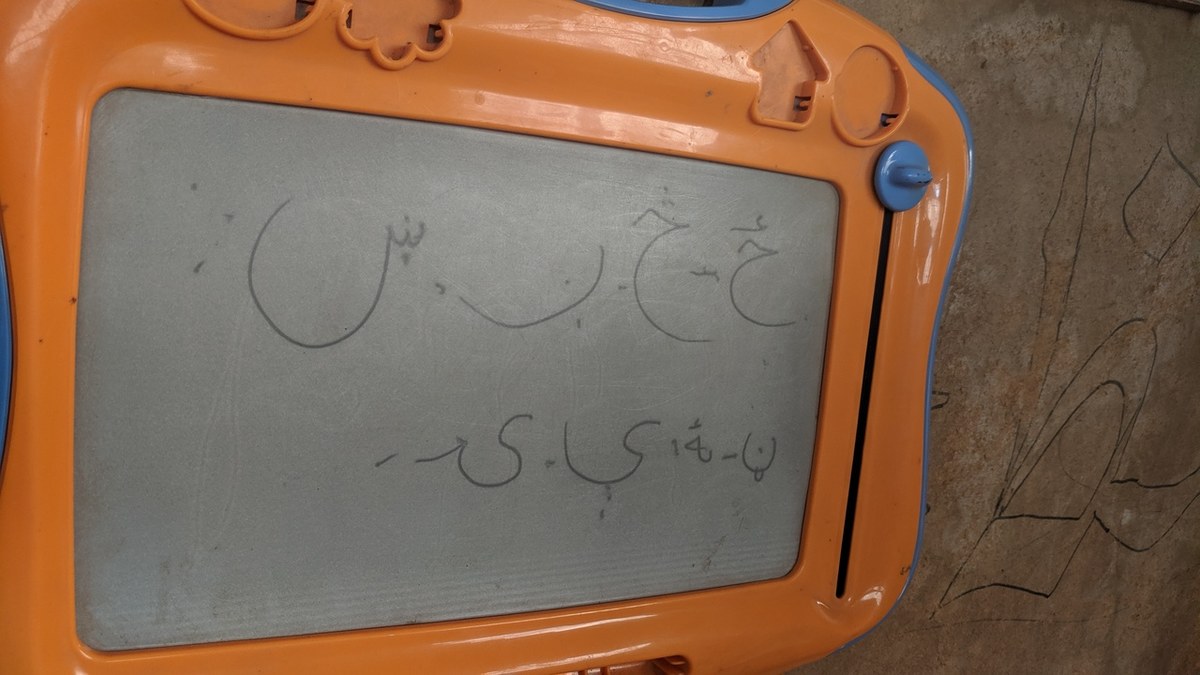

Fazal Khaliq Ghamgeen, a poet and author, during a special language class for Pashto inside a seminary in the Orangi Town of Karachi. Ghamgeen says there are eight alphabets in Pashto which cannot be found in Arabic and Persian, from where most of its alphabets are derived from. (AN Photo)

“We are taught English, Urdu and Sindhi at school but not my mother tongue, Pashto, so when I heard about the class, I quit everything to make use of the opportunity,” Omar told Arab News, adding that his parents encouraged him to take the classes.

“My father said ‘Zoyia (son), I can’t read my language, you should atleast’,” he added.

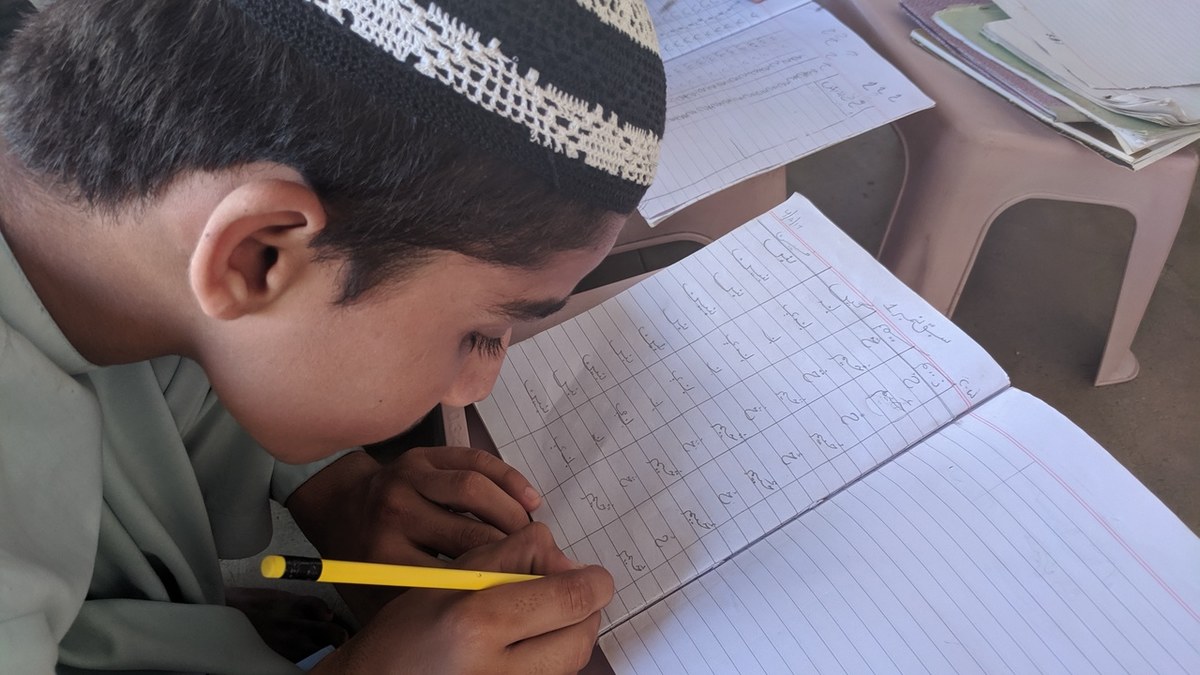

Siddiq Omar, a 15-year-old student, writes down lesson number one of the Pashto language class inside a seminary in the Orangi Town of Karachi on Friday. (AN Photo)

The Pashtuns, who hail from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, northern Balochistan and Afghanistan, form Karachi’s second-largest ethnic group, after those who speak Urdu.

An estimated six million Pashtuns reside in Karachi, making it the largest city in the world to host the community. In simpler terms, it means that there are more Pashtuns in Karachi than in Kabul, Peshawar, Quetta, and Kandahar.

At present, they make up 25 percent of the city’s population, but Qaiser Bengali, a reknowned economist, estimates that the number could go up to 33 percent by 2045.

The increasing population, coupled with other political changes, has helped several community members attain seats in the national and provincial assemblies, while the leader of opposition in the city council belongs to the Pashtun community, too.

A majority, however, continue to mourn the loss of their native language, with several having forgotten how to read or write it.

“Learning to read or write in Pashto hardly ensures any jobs. Therefore, the interest for learning Pashto is mostly for literary or academic purposes. That is why there are no formal Pashto learning efforts within the community,” Ali Arqam, a language teacher at the Habib University said.

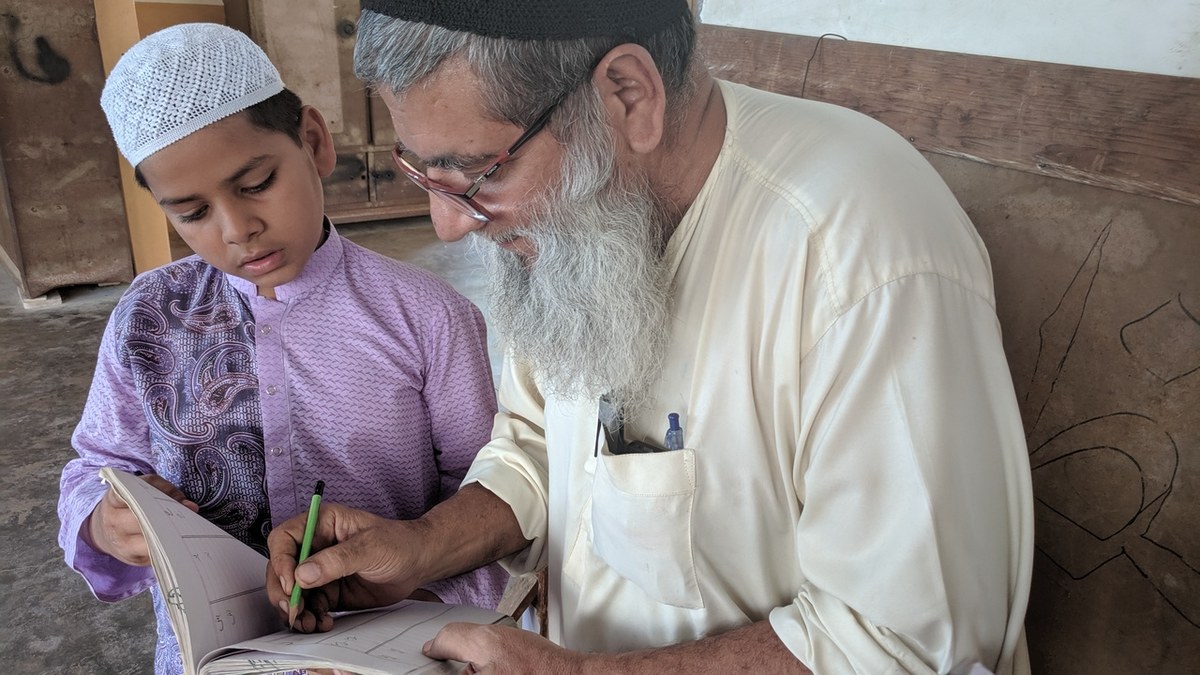

Muhammad Anas, a Punjabi student with an interest in learning Pashto has his work checked by his teacher, Fazal Khaliq Ghamgeen, at a seminary in the Orangi Town of Karachi on Friday. (AN Photo)

Arqam was part of a group that launched a social development program, under the Arzu center for regional languages and literature.

The program has since been discontinued, but Arqam – who has been a close part of Ghamgeen’s Pashto revival efforts in the city – says learning the language is very important and matters a lot.

“It always hurts me when I see a Pashtun who is unable to read and write in his language,” Ghamgeen, on a brief break from his hour-long class, told Arab News.

He says a month ago, he was invited to the madrassa’s annual certification ceremony as a guest. It was here that he enquired whether the 930 children – which the madrassa provides basic religious education to – could read or write in Pashto.

Seen here is the first floor of the Jamia Masjid Khyber, an Islamic seminary which is used for teaching Pashto language every Friday. (AN Photo)

“The answer was “no.” Soon after, I requested my friend, the prayer leader, Usman Ghani to allow me hold a class of Pashto inside the seminary,” Ghamgeen said, adding that 18 children have signed up for the class thus far, optimistic that the “number will grow.”

As the class ended, Muhammad Anas, one of the two Punjabi students from the course, ran toward Ghamgeen to check whether he had rightly written an alphabet correctly.

“We speak Punjabi at home but can speak Pashto as well. Now, I am learning to read and write it,” Anas said.