BEIRUT: Lebanon’s ninth day of anti-government protests witnessed a change in pace as clashes erupted between Hezbollah supporters, protestors and riot police, before and after the group’s Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah’s speech.

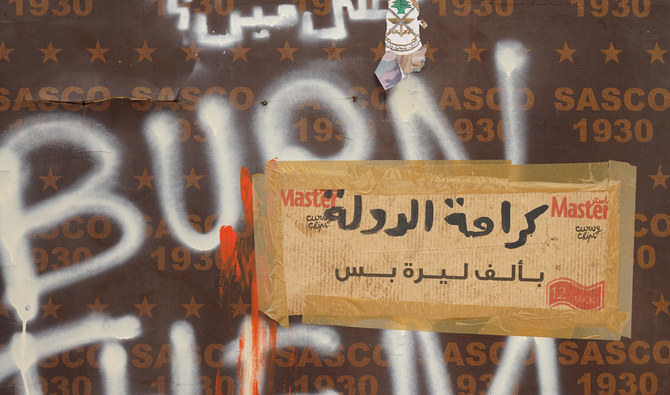

Several people were injured as both sides hurled projectiles at one another. It was a dramatic shift from the morning, when people in Beirut’s Martyrs Square and Riad Al-Solh calmly set up stands of Lebanese merchandise, and vendors prepared their food offerings.

Riot police were forced to intervene between both sides in an attempt to deter the projectiles following Nasrallah’s speech — which was decried as similar to an earlier address given by Prime Minister Saad Hariri.

“They’re all the same: Hariri, Nasrallah, Aoun, Bassil,” Alaa Mortada, one of the protestors, told Arab News.

“Look at what they’re doing. Aren’t we all Lebanese? This is why we need to remove religion from politics,” he added.

Nasrallah continued to throw his weight behind the Hariri government, claiming that the protests were an “achievement” since they pushed the government to announce a budget with no tax.

“We don’t accept toppling the presidency, we also don’t back government resignation,” he said, adding: “Lebanon has entered a dangerous phase, there are prospects that our country will be politically targeted by international, regional powers.”

He ended the speech by urging his supporters to leave the protests. Several arrests were made following the clashes.

Similar scuffles broke out on Thursday night at the same site in central Beirut.

Following the scuffles more riot police with masks and batons were dispatched to the square to defuse the situation, which appeared to be growing more tense.

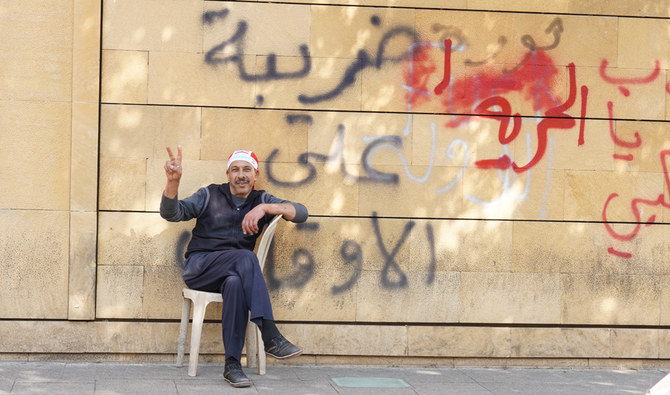

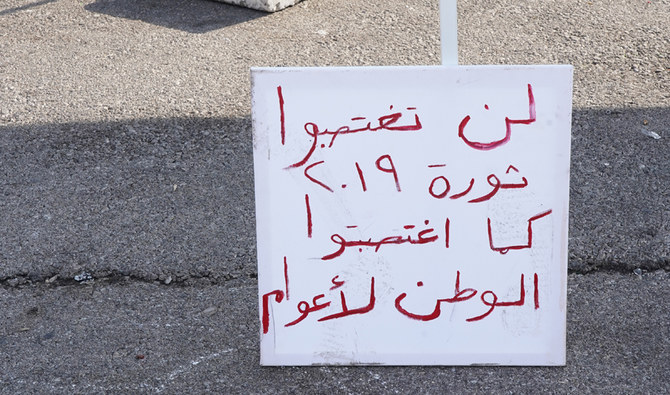

The demonstrators, who have thronged towns and cities across Lebanon prompting the closure of banks and schools, have been demanding the removal of the entire political class, accusing it of systematic corruption.

Numbers have declined since Sunday, when hundreds of thousands took over Beirut and other cities in the largest demonstrations in years, but could grow again over the weekend.

Lebanon’s largely sectarian political parties have been wrong-footed by the cross-communal nature of the demonstrations, which have drawn Christians and Muslims, Shiite, Sunni and Druze.

Waving Lebanese national flags rather than the partisan colors normally paraded at demonstrations, protesters have been demanding the resignation of all of Lebanon’s political leaders.

Volunteers clear trash in a mass clean-up in central Beirut on Friday, October 25, 2019. (AFP)

In attempts to calm the anger, Prime Minister Saad Hariri has pushed through a package of economic reforms, while President Michel Aoun offered Thursday to meet with representatives of the demonstrators to discuss their demands.

But those measures have been given short shrift by demonstrators, many of whom want the government to resign to pave the way for new elections.

“We want to stay on the street to realize our demands and improve the country,” one protester, who asked to be identified only by his first name Essam, said.

“We want the regime to fall ... The people are hungry and there is no other solution in front of us,” said Essam, a 30-year-old health administrator.

On Friday morning, protesters again cut some of Beirut’s main highways, including the road to the airport and the coast road toward second city Tripoli and the north.

On the motorway north of Beirut, demonstrators had erected tents and stalls in the center of the carriageway.

But there was no sign of any move by the army to try to reopen the road.

In central Beirut, where street parties have gone on into the early hours, groups of volunteers again gathered to collect the trash.

“We are on the street to help clean up and clean up the country,” volunteer Ahmed Assi said.

“We will take part in the afternoon to find out what the next stage will be,” said the 30-year-old, who works at a clothing company.

Lebanon’s Al-Akhbar newspaper, which is close to Hezbollah, headlined its front page “Risk of chaos,” saying the movement had pledged to work to reopen blocked roads.

Hezbollah maintains a large, well-disciplined military wing.

Fares Al-Halabi, a 27-year-old activist and researcher at a non-governmental organization, said that “the Lebanese parties are trying to penetrate the demonstrations and put pressure on them or split them.”

Lebanon endured a devastating civil war that ended in 1990 and many of its current political leaders are former commanders of wartime militias, most of them recruited on sectarian lines.

Persistent deadlock between the rival faction leaders has stymied efforts to tackle the deteriorating economy, while the eight-year civil war in neighboring Syria has compounded the crisis.

More than a quarter of Lebanon’s population lives in poverty, according to the World Bank.

The post-war political system was supposed to balance the competing interests of Lebanon’s myriad sects but its effect has been to entrench power and influence along sectarian lines.

— With input from Reuters