RATODERO, SINDH: The first thing Laila Shehzada remembers thinking when she tested positive for HIV at Ratodero Treatment Center in southern Pakistan, was that she should have died before the screening.

When she came home, it was to a different life, and Shehzada was instantly considered an ‘untouchable.’

“My pots and food were separated. I was asked not to touch anything. My husband was strictly prohibited from coming close to me,” the 25 year old told Arab News, her face streaming with tears.

“I thought, I should have died without being tested. At least I wouldn’t be dying every moment of every day,” she said.

She is quarantined together with her son, who also tested positive for the virus.

“In only a moment, we became untouchables,” she said.

Laila Shehzada, who tested positive for HIV, gets her son examined at a private clinic in Ratodero, Larkana in southern Pakistan on Nov. 29, 2019. (AN photo)

When almost 900 children in the small Pakistani city of Ratodero in Sindh province became ill and bedridden earlier this year, the disease was pinned down. And the diagnosis, revealed in April, was devastating: The city was the epicenter of an HIV outbreak that overwhelmingly affected children. Health officials initially blamed the outbreak on a single pediatrician, saying he was reusing syringes, but after a short arrest, the court released him on bail in June.

Families of HIV affected children in Subhani Shar village of Ratodero in Southern Pakistan share stories of their isolation on Nov 29, 2019. (AN photo)

From the 37,070 people screened after the April outbreak, 1,176 have tested positive for the virus. Of them, 936 are children and 429 of them aged between 2 to 5 years, according to a Sindh AIDS Control Programme report. And out of a total 41 AIDS related fatalities since the outbreak, 38 have been children.

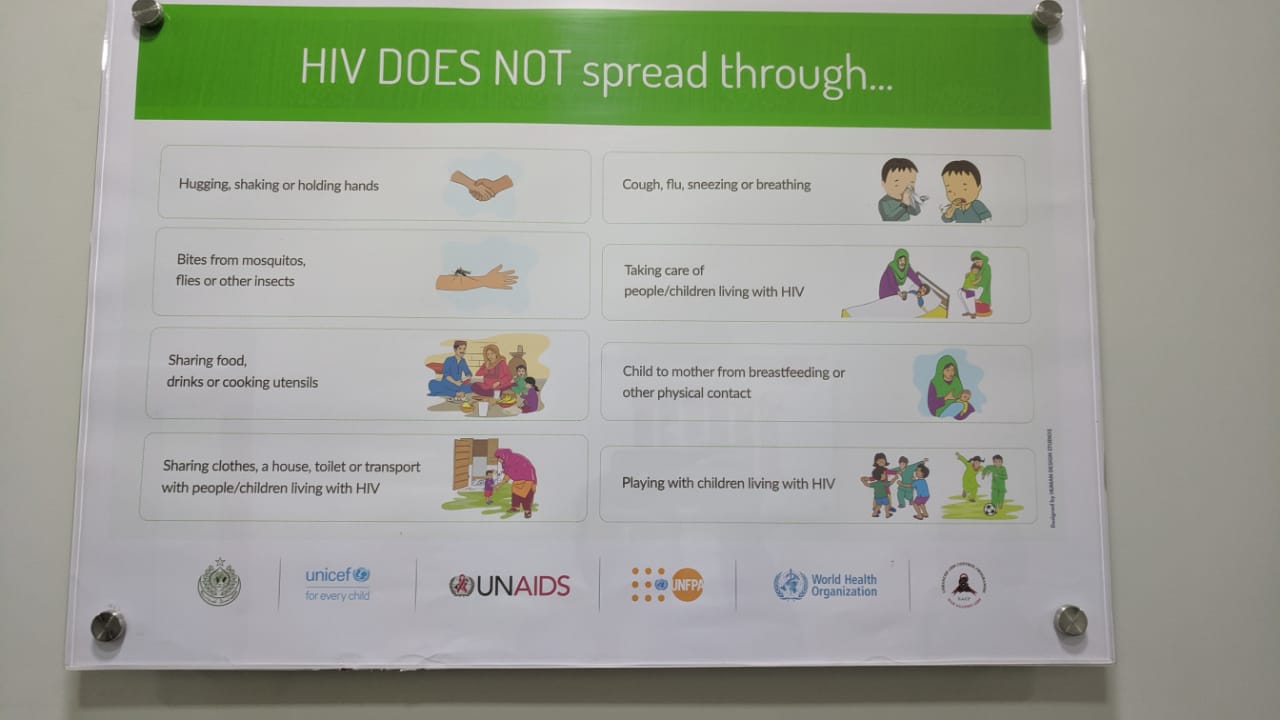

Awareness material in English is displayed inside Ratodero treatment support center in southern Pakistan on Nov. 30, 2019. (AN photo)

According to a WHO team of experts who visited Larkana in May, the major cause of the outbreak was the repeated use of unclean needles and syringes and unsafe blood transfusions.

Speaking to Arab News, Dr. Safdar Kamal Pasha, who consults for the WHO on HIV/AIDS in Pakistan, said: “Unsafe injection practices and poor infection control are among the most important drivers of the outbreak.” He also noted that this was not the first outbreak of HIV cases in Sindh.

Heer (center) and Rabel (right) said they are worried about the future of their HIV infected children after social boycotts against them in Ratodero in southern Sindh province. (AN photo)

HIV continues to be a major public health issue in Pakistan and worldwide. From 2010 to 2017, new HIV infections in Pakistan increased by 45 percent-- one of the highest rates in the region. There are an estimated 165,000 people living with HIV in the country, according to WHO.

But worryingly, a confidential health department report seen by Arab News suggests a sharp decline in screening trends. The number of weekly screenings have dropped from over 5,000 in the beginning of the outbreak to 180 by the third week of November and with the rates of disease showing no signs of slowing down.

Dr. Ghulam Shabbir Imran Arbani, the first medical practitioner to report HIV cases to the media in April 2019, talks to Arab News from his office on Nov 29, 2019. (AN photo)

Dr. Ghulam Shabbir Imran Arbani, the first medical practitioner to report the HIV cases to the media, says it is the social taboo and attitude surrounding the disease, that discourages others from getting screened.

Though the provincinal health department claims it has cracked down against quacks and illegal blood banks, Dr. Arbani said the source of HIV infection still prevails.

“Unauthorized laboratories are functioning, jewellers are using unsterilized needles for ear piercings, barbers are following unsafe practices and there is no action taken against quacks,” Dr. Arbani said and added there should be mass and mandatory screenings.

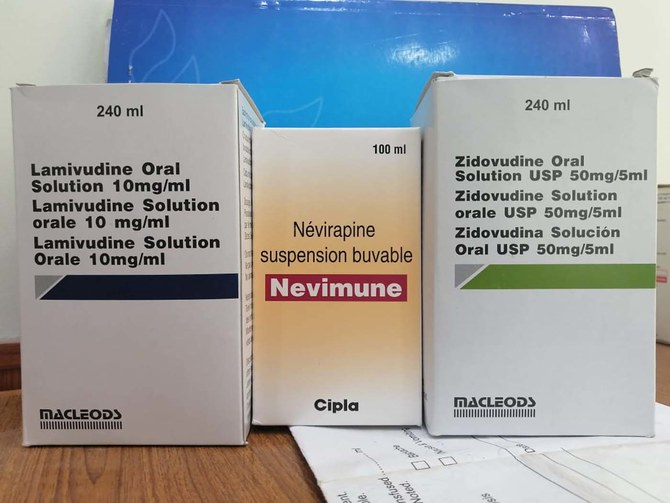

“The patients coming to me complain of treatment without the periodical assessment of a viral load,” the practitioner said, referring to a measure of the number of HIV viral particles present in the bloodstream.

The facade of the Ratodero Treatment Support Center in southern Sindh province on Nov. 29, 2019. (AN photo)

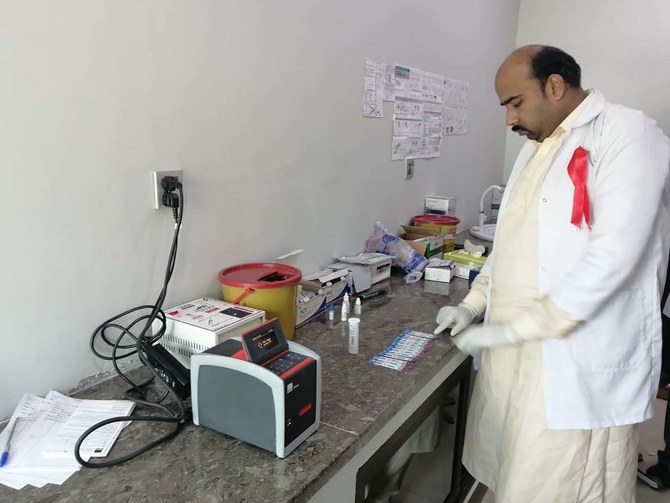

But at the Ratodero treatment center, in the small town that became the axis of the outbreak, officials in charge said both treatment and awareness was being given to residents and patients.

“We are providing best possible treatment whereas awareness is also increasing,” said Dr. M. Tegh Bahadur, who runs the treatment center.

Imtiaz Ali, shows a video of his young daughter, who is infected with HIV, crying from pain at his home at Ratodero town in southern Sindh province on Nov 29, 2019. Five of Ali’s six children tested positive for the virus and two have died from AIDS. (AN photo)

But the awareness, it seems, is not yet changing powerful social norms and taboos that dictate behavior around the illness. In May, a woman, Zareena Rind, was killed by her husband after she tested positive for HIV.

Imtiaz Ali, who lost two of his HIV infected five children, said he had to leave his village after a complete boycott by his extended family.

“I fell unconscious when the screening results of five of my six children came back positive,” Ali said.

“I could hardly walk back home. In less than an hour, when I shared the news with my family, my own father picked up his belongings and moved to my brother’s house. My brother completely boycotted me and I had to leave the village,” Ali said, who now lives in a small rented house in town.

“No one has contacted me,” Ali continued.

In Subhani Shar, a village of nearly 600 families, 31 children from 27 families have tested HIV positive. “We were told to leave our ancestral homes and set up our own village away from the rest, as people think HIV can be transmitted to them through the air,” Fida Hussain, the parent of an infected child, told Arab News.

“Our children may survive,” said Shehzado Khatoon, rocking her infant HIV infected son in her arms.

“But this attitude is killing us,” she said, as other parents around her nodded in agreement.