PARIS: Gerard Mestrallet is executive chairman of the French Agency for the Development of AlUla (Afalula), the Saudi heritage site that is fast becoming an international cultural and tourist attraction.

AlUla, in the Kingdom’s northwest, is known for its natural beauty and archaeological diversity.

It has hosted major cultural events, including a site-responsive outdoor art installation featuring the work of Saudi and international artists, and a music festival with world-famous stars.

FASTFACT

French gastronomy has been an important part of the Winter at Tantora Festival, which will continue in AlUla until March 7.

Earlier in February, it announced that the Kingdom is planning to develop AlUla into the world’s largest living museum and a major cultural, arts, adventure tourism and heritage destination.

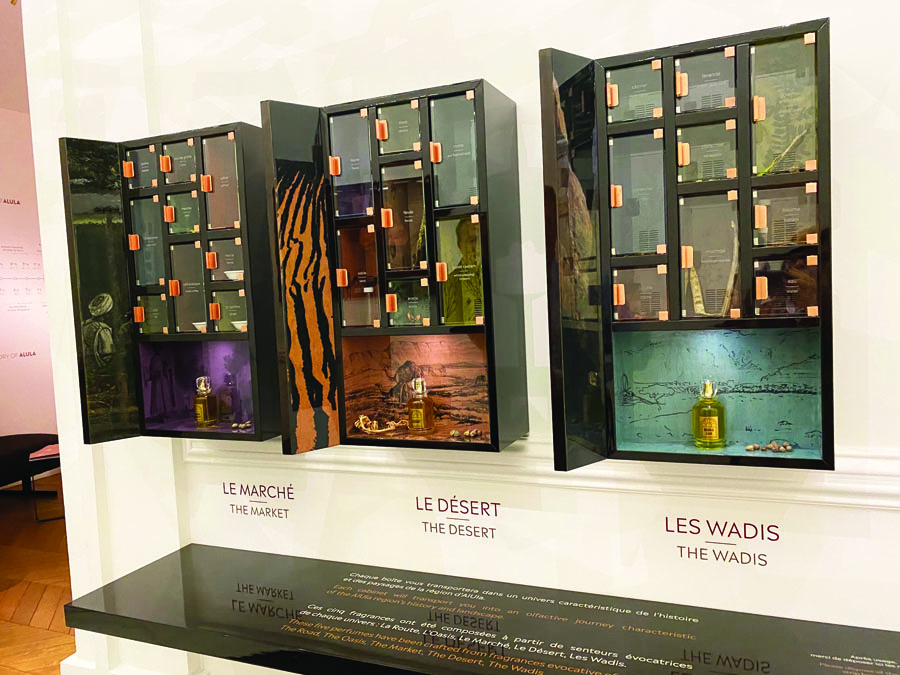

Mestrallet spoke to Arab News from Afalula’s Paris office, where pictures and videos of AlUla welcome visitors, and perfumes produced in AlUla with the expertise of Grasse, the southern French city renowned for fragrance, tickle the senses.

He talked about how the agency and France will contribute to the development of a site that forms a vital part of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 reform plan.

“French President Emmanuel Macron appointed me to head the agency for the development of AlUla because I’d previously managed Engie and Suez, which contributed to important world projects and had invested massively in water treatment, desalination of seawater, and electricity production in Gulf countries,” Mestrallet told Arab News.

Afalula’s Paris office, right. (AN photo by Huda Bashatah)

“When Macron met the crown prince, the prince asked him for French support for the development of AlUla, and the president entrusted me to negotiate the development and to create a French agency for AlUla on the model of the French agency for the (Louvre) museum that was created in Abu Dhabi,” he said.

“We negotiated with the Royal Commission for AlUla (RCU) before the Crown Prince’s visit to Paris in April 2018, and we were prepared. The agreement was signed at the Elysée Palace during the crown prince’s state visit.”

The agency’s creation was defined in a treaty between France and Saudi Arabia, Mestrallet said.

“We have a dual role — on the one hand, to plan the project jointly with the RCU, and on the other hand, to mobilize the vast range of French expertise in all areas of the project: Engineers, architects, urban planning, infrastructure for roads, energy, transport, water and gastronomic training,” he said.

“We have access to renowned French chefs in AlUla, but young Saudis are also given gastronomic training in France. We also have contributions from major French cultural institutions such as the Louvre, Chambord, Versailles, and we have access to French knowledge relating to tourism, hotels and security.”

He said the team comprises 30 highly qualified people. The architecture and urban planning sector are headed by Etienne Tricaud, former president and founder of AREP, the biggest architectural firm in France.

Tricaud was so efficient, according to the Saudis, that he was given the responsibility to integrate both teams — the French one and the RCU’s — into a single entity.

Gerard Mestrallet, head of the agency for the development of the site

Nicolas Lefebvre, head of Afalula’s department of tourism and hospitality, along with the CEO of the Eiffel Tower Co., have been charged with making the site a leader in sustainable tourism.

Mestrallet said: “For security, the head is Bernard Petit, the former chief of the Paris Police Judiciaire. For botanical products and concepts, we have Elizabeth Dodinet, with over 20 years’ experience in archeology, ethnobotany and aromatic plant research.

“Then we have Regis Dantaux, in charge of human resources; Charles Chaumin, in charge of water and the environment; Stephane Forman, in charge of agriculture; and Jean-François Charnier, scientific director.

“Clearly, we have an exceptionally high level of expertise that France is making use of in order to make this Saudi project a success in every sense.”

Mestrallet said the masterplan represents what the project will be in 10-20 years, with resorts, hotels and museums, and there are plans for eight museums to be built.

One project is from the French “star-chitect” Jean Nouvel, who built the Louvre in Abu Dhabi. Nouvel is designing a hotel complex in Sharan Nature Reserve. The project was the crown prince’s idea before the RCU was officially created, Mestrallet said.

An architecture competition was organized for a hotel complex, and Nouvel won. “I was part of the international jury that selected him, and his project is really amazing,” Mestrallet said.

“It will be built entirely in the rock, and will thus have a minimal impact on the nature reserve.”

ALSO READ: French engineer returns ancient coins to AlUla

The AlUla project is on a site the size of a small city, and Afalula will take part in its future development.

“There will be billions in investments, but it will be essential for us to respect the site, its natural features, the heritage, principles and rules for sustainable development, and its impact on the local populations. It is thus a complex challenge,” Mestrallet said.

“These principles are part of the Crown Prince’s Vision 2030, and are included as part of the treaty between France and Saudi Arabia. French companies will take part just like others in tenders, and we’re here to assist and mobilize them.”

Saudi Arabia aims to host 2 million visitors per year in AlUla by 2035. The RCU, which is responsible for protecting and promoting the area, estimates that the project will create more than 67,000 jobs, almost half of them in the tourism sector.

Around 80 percent of AlUla county will be protected, including cultural and natural heritage sites.

Mestrallet said the first masterplan will be finished in six months. “We’re very happy to be associated with this project, which touches upon the soul of Saudi Arabia and will have a huge impact,” he said.

“The project is linked to 7,000 years of history in the Kingdom, and by developing it, King Salman and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman want to reveal this history to their people. Our role is to use French expertise in order to serve this purpose.”

There will be a large research center on Arab civilization, and eight museums in AlUla.

One museum will be dedicated to modern art, and Afalula is relying on revered French cultural institutions such as the Pompidou Museum to participate.

Another museum is devoted to the Nabatean period, and other museums will focus on horses, astronomy, minerals, perfumes and oases.

French gastronomy was an important part of the second year in the Winter at Tantora festival, which takes place every weekend for 10 weeks from the beginning of December, Mestrallet said.

“A concert hall has been built in the desert, as well as housing for the festival. There’s a magical spot, surrounded by Nabatean tombs, which features an open-air restaurant where many-starred Michelin French chefs visit and cook. Some of these are Anne Sophie Pic, who has two three-star restaurants and another with two stars.

The first female French chef who came was Hélène Darroze. Other outstanding chefs included Yannick Alleno of Le Doyen restaurant in Paris; Guy Martin, chef of the Grand Vefour restaurant in Paris; and Arnaud Donckele, the three-star chef of the Cheval Blanc hotel in St. Tropez, who will open a Cheval Blanc restaurant at the Samaritaine department store in Paris.”

The AlUla project aims to open the Kingdom to the world, Mestrallet said, adding: “It’s an immense privilege for us to follow up on the French president’s decision to participate in the creation of this project.

“We want to be sure that the project is respectful of sustainable development, the wellbeing of the environment, and its effect on all the local populations.”