CAIRO: Former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, who passed away on Tuesday, ruled Egypt for 30 years. His rule began in a spirit of reform, with the release of political prisoners, support for the independence of the judiciary and the freedom of the press and a great deal of tolerance for his political opponents.

CAIRO: Former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, who passed away on Tuesday, ruled Egypt for 30 years. His rule began in a spirit of reform, with the release of political prisoners, support for the independence of the judiciary and the freedom of the press and a great deal of tolerance for his political opponents.

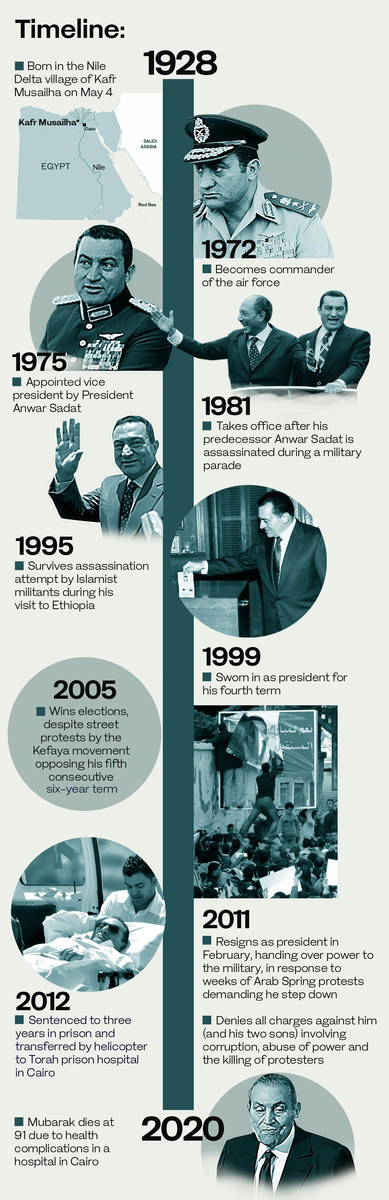

What is certain is that Mubarak’s role in the contemporary history of Egypt lies mainly in the military, as he belonged to a generation of warrior leaders. He was chosen by Gamal Abdel Nasser after the defeat of 1967, when he was a colonel, in order to rebuild the destroyed air force and prepare it for the victory of October 1973.

Some may disagree about Mubarak’s legacy, but it is unfair and transgressive to underestimate his value and role as a pilot.

I will not forget a comment, from a friend of mine from the Gulf, on the change he witnessed in the character of Egypt during the country’s rush to try Mubarak, and even execute him, after his fall. “The crisis that the Egyptian people suffer from is that, for the first time, they have lost their two most important characteristics: Patience and tolerance,” he told me.

I will also never forget the comment of an English friend during Mubarak’s trial, and his transfer from his home to the hospital, and from there to the courtroom cage that had been specially built for him, and then to prison. At that time, my friend wondered: “Didn’t Mubarak fight with the army one day?” I replied: “He even participated in three wars: The Suez war in 1956, the June 1967 war, and finally the October 1973 war, which was truly the most important victory in the history of the Arabs.” The man marveled at the insult Mubarak had to endure, saying: “Had he been in my country, the situation would have been different.”

He resigned as president in 2011, ushering in elections won by the Muslim Brotherhood. (AP)

For sure, Mubarak belonged to the generation of great warrior leaders, and that is an undeniable role that cannot be erased. At the same time, he was the ruler of Egypt for 30 years, and he is certainly subject to criticism, agreements and differences.

It is possible to explain a part of Mubarak’s behavior on the eve of his removal from power in order to preserve the blood of the Egyptians, and his decision to remain in the country, by saying that he was a leader who fought for the sake of Egypt. He did not kill tens of thousands or destroy cities to remain in power. He did not run away from the accusations leveled against him. Rather, he was tried in his country as a former president — acquitted in some cases and convicted in one — which gave a symbolic value to Egypt.

I still remember when he said to me with love and pride, after I interviewed him in 2009, how he preserved all of Egypt’s history and topography, and how he had visited all of its cities. He spoke with a real passion, one that explains why he did not leave the country when he abdicated.

The trials of the former president were not the most severe acts against him — that, I think, was the moment when his successors decided to withdraw all the medals and decorations he had received from him. I think that was the most difficult moment.

Many believe — and I am one of them — that a politician’s accountability for his errors should be in political action. I do not agree that accountability and justice for what are deemed political errors should be meted out through the use of vindictive punishments.

His final years as president saw rising discontent against him. (AFP)

There are those who considered Mubarak’s reign as three decades of darkness and dictatorship, of looting, corruption and retreat, but it can be noticed that the number of these people has decreased significantly during recent years. On the other hand, there is a large sector that believes Mubarak made right and wrong decisions, and these people believe that, had Mubarak decided to withdraw from public life after the death of his grandson in 2009, and the surgery he underwent, he would have had a distinguished position in the hearts of the Egyptians. There is a third group that calls itself “Mubarak’s children.” These people find in their former president nothing but good, and their position was strengthened because of the way the Muslim Brotherhood ruled.

So, as we see, there are understandable difference in assessing Mubarak’s legacy. What was not understood, however, was the sweeping and overpowering attack not on Mubarak the president, but on Mubarak the fighter pilot — Mubarak the man.

God was merciful to him. He gave him the chance to see a large part of his rehabilitation after he suffered a lot during the long months following the fall of his regime in 2011. He was ultimately cleared of all charges but, more importantly, he began to talk again about the role of the air force. His memoirs, which he wrote when he was vice president, were published to show him as a military commander and a fighter pilot who fought for his country.

For many Egyptians, it seemed he had been helped through divine intervention. He entered intensive care about a month ago. A few days before his death, he received the news that his sons, Alaa and Gamal, had been acquitted in their final case. And one of the last things Mubarak said, according to his lawyer, Farid Al-Deeb, after he learned of the news of the innocence of his two sons, was: “Praise be to God. Our Lord has done justice to us after so many years.”

People will always remember that Mubarak gave a real margin to political forces and the media throughout his rule. This was one of the reasons he remained in power for so long, and was not the cause of his downfall.

Dr. Abdellatif El-Menawy is a critically acclaimed multimedia journalist, writer and columnist who has covered war zones and conflicts worldwide. Twitter: @ALMenawy