DUBAI: Calligraphy is one of the most important, sacred and characteristic expressions of Islam and the non-Muslim Arab world and has continually evolved and adapted since its formal introduction in the seventh century.

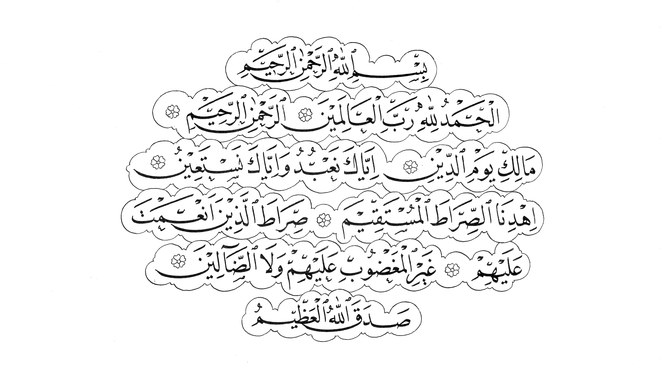

Styles such as Naskh have held strong and stayed relevant, opening up fresh channels of spiritual interpretation and contemporary use.

Naskh has been widely used throughout the centuries to copy small manuscripts and scientific, literary and cultural books, as well as Qur’ans, mainly due to its high legibility, subtle simplicity and efficacy of execution.

Maryam Ekhtiar, a scholar and curator at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, said that while digitalization and technologies had “challenged the supremacy of traditional calligraphy and have gradually replaced handwritten texts,” Naskh remained relevant. The 10th-century script has been adapted to computer fonts that are used regularly in print and online publications.

Styles such as Naskh have held strong and stayed relevant, opening up fresh channels of spiritual interpretation and contemporary use. (Supplied)

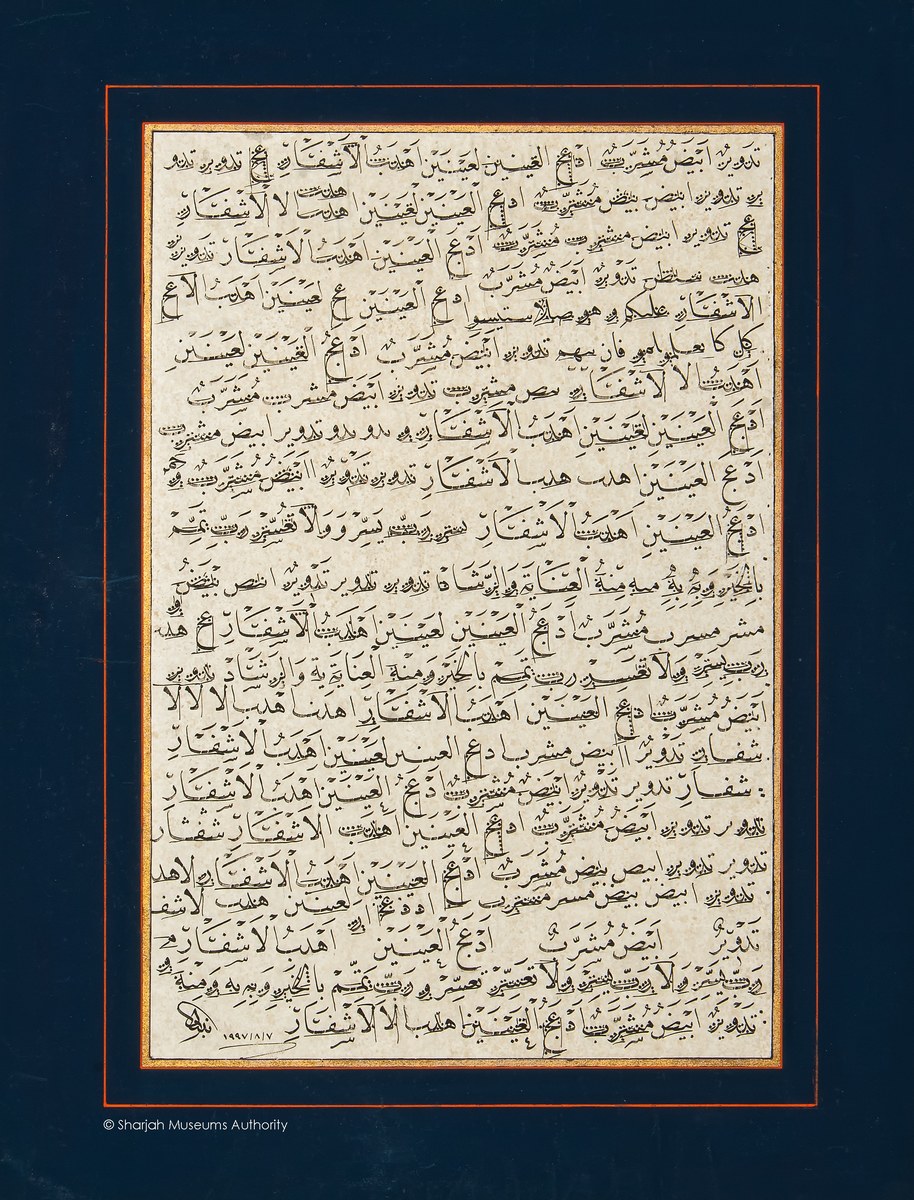

Naskh’s timeless cursive stylization was established by the Abbasid vizier and calligrapher Abu Ali Muhammad ibn Muqla. Following aesthetic rules, an elegant, smaller and more delicate Naskh emerged as one of six classical proportional scripts alongside Thuluth, Muhaqqaq, Rayhani, Tawqi’ and Riqa’.

Ibn Muqla’s system was based on a series of ratios around two shapes: a circle with the diameter of the letter Alif—and rhomboid dots created by the stroke of a calligrapher’s reed pen nib.

Similar to other Arabic scripts, Naskh features a straight stroke Alif and differentiates sounds through letter pointing in the form of one to three dots above or below letters, and engages a horizontal baseline, save for when a letter begins with the tail of a preceding letter.

Master calligrapher Ibn Al-Bawwab and Yaqut Al-Musta’simi further refined Ibn Muqla’s system, with enhancements and innovations. By the 17th century in Iran, Ahmad Nairizi’s revival Naskh rendered the script larger and more readable with spacing, clear bold letters and vocalization marks.

Historically utilized more frequently in books and administrative documents than for Qur’ans, Naskh and Kufic lent themselves seamlessly to abstraction, foliation and pictorial ornamentation.

Naskh’s timeless cursive stylization was established by the Abbasid vizier and calligrapher Abu Ali Muhammad ibn Muqla. (Supplied)

Such embellishments provided calligraphers, illuminators and bookbinders with the double opportunity for experimentation and compositional innovation while remaining a pious act and conveying meaning.

However, as the expansion of the calligraphic practice resulted in more complex roles and meanings for the act and outcome, Ekhtiar noted scholar Sheila Blair’s assertion that the challenge for the calligrapher became an “ambiguity of purpose” — finding the balance between “the rigors of the calligraphic discipline, the communication of information, and the desire to instill wonder in the viewer.”

Ekhtiar pointed out that the tension between verbal clarity and design was neither new nor modern. In Khurasan metalwork from the 10th century, as well as calligraphic works from 12th- to 13th-century Mosul, Naskh playfully adopted anthropomorphic forms.

“In my exhibition, ‘The Decorated Word: Writing and Picturing in Islamic Calligraphy,’ I showed that this interplay has been a distinguishing feature of Islamic calligraphy for centuries and is traceable to the early Islamic era,” she said.

From the late 15th and 16th centuries onward, there were many instances in which abstraction and ornamentation overshadowed verbal clarity. Calligrams — pictorial calligraphy — for example, became increasingly popular in 18th and 19th century Ottoman Turkey and Deccan India. It is a tendency that continues in modern and contemporary expressions of calligraphy, beginning in the mid-20th century.

Lilia Ben Salah, co-founding director of Dubai’s Elmarsa Gallery, said: “There’s been a real evolution — it was very avant-garde when artists started experimenting with new forms of Arabic calligraphy in the 1940s and 50s.

“Artists today use calligraphy the same way modernists used surrealism or abstract expressionism — it’s an artistic expression. It’s not rebranding, but the use, means and expression have been transformed within a contemporary art context.

“But it’s very cultural. Artists like Hossein Zenderoudi, Nja Mahdaoui, Khaled Ben Slimane and Rachid Koraichi use it in different visual approaches to express spirituality. They have really created their own language from their historical, cultural backgrounds,” added Ben Salah.

Although traditional calligraphy is not practiced widely today, Naskh continues to be a relevant script, opening doors for discussions on the wider uses and evolutions of calligraphic fonts, and its use by modern and contemporary artists.

“Some artists reinforce calligraphy’s historical and traditional ties, while others use this art form to express political, social, and economic issues, and questions of national and personal identity,” said Ekhtiar.

Tunisian Mahdaoui actively subverts calligraphic foundations in order to “freely exit the graphic structure of the Arabic letters or the verb syntax and the structure of the style.”

He said: “I believe that the final objective is a work of art in which materials are meaning-loaded symbols. I have tried to extract the original signification power of these materials in order to achieve an aesthetic of form. While exclusively working on form, regardless of its meaning, I enjoy the freedom of presenting all the combinations that I like.”

Ben Salah said that contemporary interpretations had taken calligraphy to another dimension that had allowed globalized younger generations to tap into the tradition, adding that there remained infinite possibilities for creative investigation.

Scripts such as Naskh, which remain relevant while also leaving room for inventiveness, indicate the staying power of its style as well as that of Islamic calligraphy as an art form.

“Many contemporary artists not only deem it relevant but continue to explore the versatility and the infinite artistic possibilities of the Arabic letters, using the art of writing as the basis for a new visual language. This will hopefully continue for generations,” added Ekhtiar.