DHAHRAN: In her new book, “Modesty: A Fashion Paradox,” which was launched at the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature in Dubai last month, UAE-based journalist Hafsa Lodi looks at the causes, controversies, and key players behind the worldwide modest-fashion trend.

Drawing on Lodi’s own experiences and her decade-long career in fashion journalism, the book serves as a comprehensive guide to modest fashion as a mainstream trend that’s here to stay, the role modesty plays in secularism and feminism, and the concept of modest fashion in a religious context.

Lodi begins by describing women like herself — but also hijabi models such as Halima Aden, fashion bloggers like Ascia Al-Faraj, social-media influencers including Dina Tokio — for whom faith plays a major role in guiding their fashion and lifestyle choices. These women lead a balanced lifestyle that “allows for both style and spirituality, where they can indulge in contemporary cultural trends…without compromising their faith,” Lodi says.

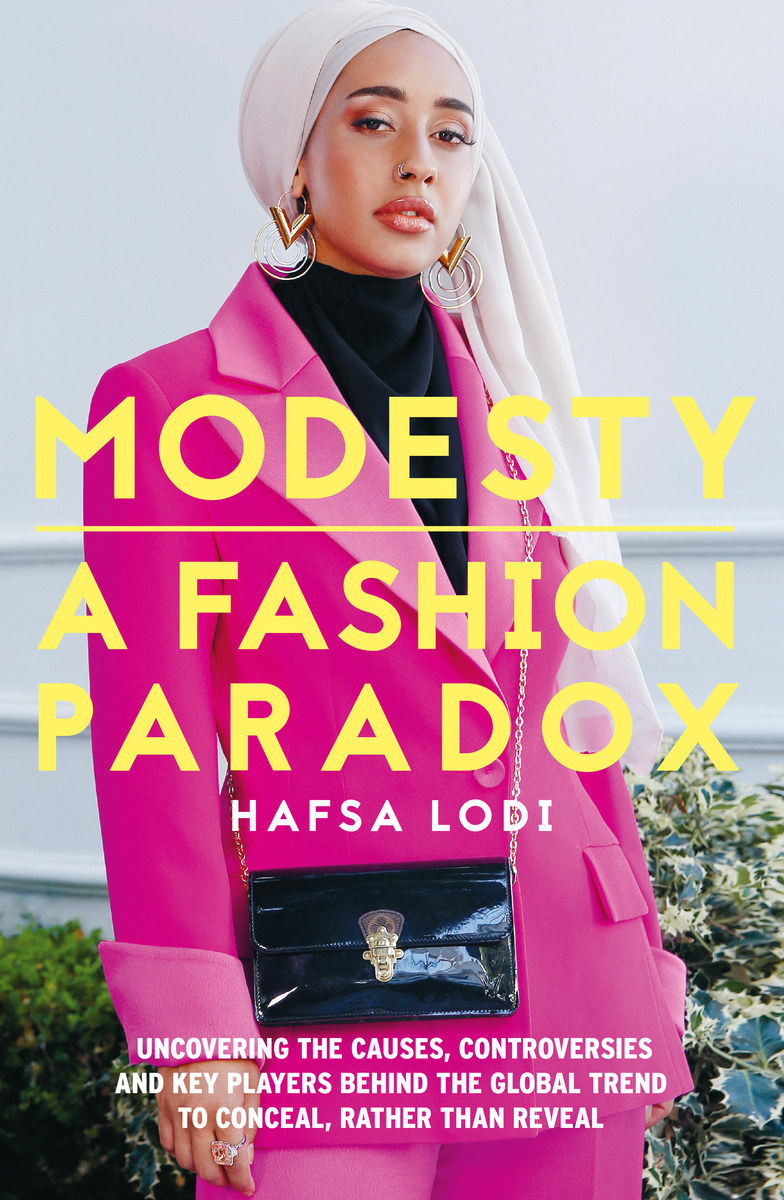

Hafsa Lodi is a UAE-based journalist who looks at the causes, controversies, and key players behind the worldwide modest-fashion trend. (Supplied)

While, in the past, dressing modestly might have been considered dowdy, old-fashioned, and even repressive, “Now, modesty has become a bit of a buzzword,” Lodi told Arab News. In the book, she chronicles how, as early as 2009 — as part of a project commissioned by Saks Fifth Avenue in Saudi Arabia — Christian Dior debuted designer abayas. Coupled with the rise of social-media influencers, hijabi models, and online retail platforms, the movement really took off in 2015, when Gucci’s Victorian styles and silk scarves (worn like a hijab) made an appearance on the runway.

“These new, covered-up offerings from Gucci were lapped up by wealthy, trend-conscious consumers. Competing brands and more affordable labels were quick to follow in the fashion house’s footsteps,” Lodi writes. “Following the path of all retail trends, modest dressing started trickling down from runways to accessible luxury brands and, eventually, to the high street.”

The book serves as a comprehensive guide to modest fashion as a mainstream trend that’s here to stay. (Supplied)

In the chapter, “Why Cover Up?” Lodi compares the concept of modesty across different cultures, languages, and religions — haya (Arabic), Tesettür (Turkish) and tzniut (Hebrew). While noting that “veiling has become somewhat synonymous with Muslim women,” she points out pre-Islamic practices of veiling followed by Greek, Roman, and Byzantine cultures and Abrahamic religions. Lodi also chronicles political climates across countries that led to the ban of the hijab and alternatively, the rise of Islamic dressing as a form of resistance to colonialism and Westernization.

What began as brands and retailers cashing in on Middle Eastern and millennial purchasing power has now led to a much bigger movement that Lodi argues may not have any religious roots. In her research, Lodi quotes several academics and activists who note a collective trend of women covering or shielding their bodies — partly in response to the #MeToo movement — and suggest that a woman’s choice to cover is also an expression of feminism. Although she also attributes modest fashion’s popularity to a widespread demand for practical and comfortable clothing.

Lodi compares the concept of modesty across different cultures, languages, and religions. (Supplied)

The increasing visibility and demand for hijabi models has only amplified the debate about whether fashion (an industry that is built on models being highly visible and the clichéd truism that ‘sex sells’) can ever truly be modest. Social media is rife with critics (or, perhaps more accurately, trolls) who are quick to call out a Muslim fashion blogger who may be dressed in high-end labels and question her intentions and perceived notions of modesty.

“The whole point of modesty — as a concept — is to encourage a sense of humility, as well as privacy between the genders, and this, (critics) believe, conflicts with the inherent purposes of modelling, blogging and social media, which encourage the worldwide circulation of images,” she writes. Lodi also admits to have fallen prey to consumerism — which goes against the ideals of modest spending — and acknowledges that this is another topic that should be explored.

The increasing visibility and demand for hijabi models has only amplified the debate about whether fashion can ever truly be modest. (Supplied)

Lodi concludes that even though the women who lead this movement are constantly questioned, those questions no longer remain relevant.

“In the 21st century, it’s the freedom of choice that’s being claimed by women of all faiths or none,” she writes. “It’s the right to cover up, rather than to expose skin, that’s being championed.”