ANKARA: Since January, as coronavirus disease (COVID-19) infections seeped out of China’s borders and into the world at large, many countries were caught napping.

A few among them chose a policy of denial until the facts could no longer be concealed. Turkey is a tragic case in point.

To be sure, in recent weeks the government has adopted sweeping measures aimed at halting the transmission of the virus.

It has shut restaurants and schools, halted prayers in mosques, suspended sporting activities, restricted intercity bus travel and stopped all international flights to or from Turkey.

Mass disinfection has been carried out in public spaces in cities across the country.

Yet those steps may prove to be no substitute for being vigilant and cautious from the beginning.

According to Berk Esen, an international relations professor at Ankara’s Bilkent University, Turkey’s delay in announcing its first case gave people the false hope that it could avoid the terrible fate of Italy and Spain.

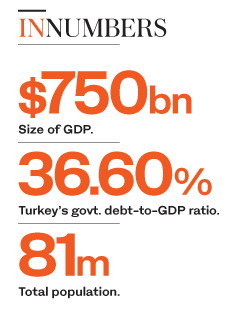

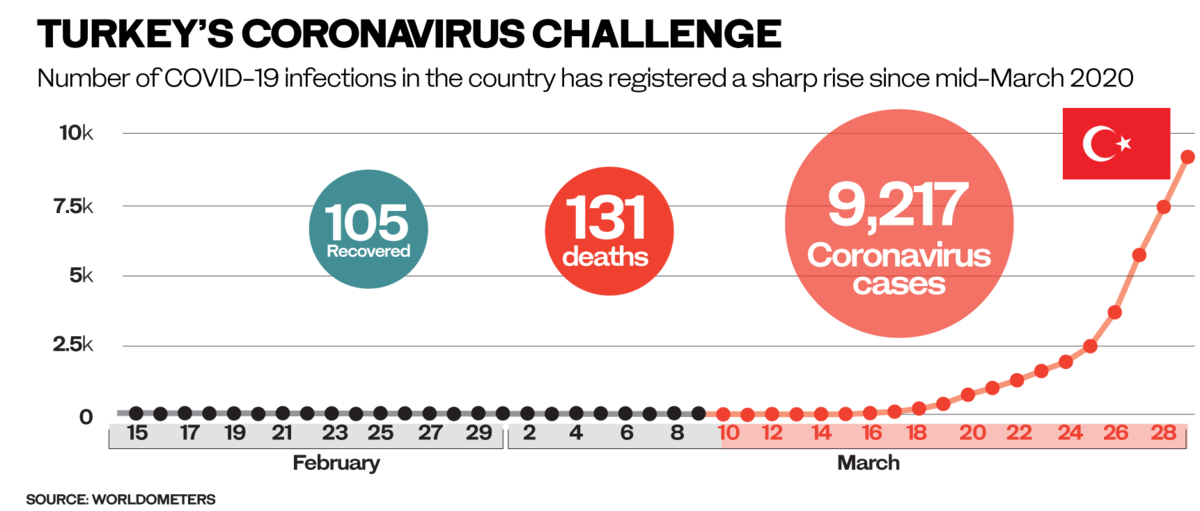

Now, with the total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases crossing the 9,000 mark, Turkey has surpassed many other countries in its rate of increase in infections.

As of Monday, the death toll stood at 131 with 105 recoveries.

“After the first case was pronounced on March 11, the crisis escalated rather quickly. The reaction of the government to the pandemic has been marked by delay,” Esen said.

“Although closing down schools was the correct decision, the government failed to quarantine thousands of visitors coming from COVID-19-infected countries.”

This public health emergency has put Turkey’s economic policies and system of governance to the test. But that is not all.

The forethought and strategy behind its involvement in the conflicts in Syria, Iraq and Libya are likewise being called into question.

The Turkish Defense Ministry says no COVID-19 cases have been reported among Turkish troops in Iraq and Syria.

Still, the government’s domestic as well international standing could suffer if it orders the sudden withdrawal of forces in response to concerns about their wellbeing.

Many experts point to the presence of ‘security contractors’ who operate in groups while assisting Turkish forces carry out cross-border operations.

Under the conditions, these contractors might find it difficult to take basic WHO-recommended precautions such as social distancing, effective handwashing and staying at home.

Overcrowding is known to be a common feature of camps in Syria, especially in northern Aleppo and Afrin, where Turkish forces are active.

“The crisis may halt Turkey’s overseas operations in Syria and Libya for now. The parties to the conflict all need to address the devastating impact of the pandemic on their populations,” Esen said.

From defense to the economy, there is no denying that Turkey faces difficult choices.

The outbreak came at a time when the country was weighed down by economic weaknesses including a vulnerable currency and very high levels of corporate and private debt.

Turkish government debt alone was expected to reach 36.6 percent of the GDP by the end of 2020.

With some experts now seeing a looming global recession, Turkey’s central bank has decided to reduce its benchmark interest rate by one percentage point.

The move is one of many precautionary measures taken by the bank to mitigate the worst impact of the global pandemic on Turkey’s $750 billion economy.

According to Nigel Rendell, director at Medley Global Advisers LLC in London, the Turkish economy is vulnerable not just to the COVID-19 crisis but also to any flight of investors from higher-risk markets.

“In recent weeks, the Turkish lira (TRY) has held up reasonably well compared with some other emerging market currencies, but it seems to have been heavily supported by central bank intervention and the actions of state banks, who have been ordered to sell dollars and buy TRY,” he told Arab News.

Some think the government is taking a “herd immunity” approach. (AFP)

According to Rendell, official interest rates have fallen significantly, to below 10 percent, and now provide little protection to those holding TRY versus some safer currencies.

“We estimate that the central bank has depleted its dollar reserves significantly and has little firepower to protect the TRY further should there be another significant sell-off,” he said.

“The risk, therefore, is that the exchange rate heads towards 7.00/dollar, and potentially lower, in the coming weeks.”

To its credit, Turkey recently announced a $5.4 billion stimulus package, but many economists see it as favoring employers rather than helping ordinary households cope with the coronavirus blow.

Many companies, especially small and medium-sized enterprises, are expected to go bankrupt and default on loan payments in the coming days.

The dark specter of mass unemployment looms over Turkey’s economic horizon.

The fear of the coronavirus situation being made worse by the flow of people has forced Turkey to seal its land borders with Iran and Iraq and halt flights to and from China, Italy and South Korea.

This in turn has affected the country’s vital tourism sector and export-based industries, whose importance in lifting Turkey from heavy indebtedness following previous economic crises cannot be overstated.

In 2018 Turkey, a major transit hub between Europe, Asia and Africa, hosted 51.8 million tourists, who brought $34.5 billion in revenue.

This year, as the coronavirus pandemic tightens its grip on large parts of the world, such a figure looks to be more mirage than reality.

Meanwhile, trade with Europe, Turkey’s main trading partner, is likely to suffer while its budget deficit (which stood at $21.77 billion last year) can only widen further.

Against this backdrop of gathering storm clouds, it is no surprise that cracks have begun to appear in the government.

On Friday night, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan took the rare step of dismissing minister Cahit Turhan, who held the transport and infrastructure portfolio.

Turhan was removed from his post with a presidential decree, but no reason was given.

The dismissal came soon after a controversial tender for the Istanbul Canal project was floated by the transport ministry.

The project involves building a huge artificial canal on the edge of Istanbul.

The timing of the tender was seen by many Turks as unseemly, conveying the impression that launching the mega-project, not protecting people from the coronavirus outbreak, was the government’s priority.

Esen thinks the Turkish government is pursuing in all but name the ‘herd immunity’ strategy that the Netherlands and UK were toying with until last week.

In the event, statistical forecasts suggest that Turkey risks a coronavirus outbreak on the same scale as Italy.

“Given how rapidly the number of cases has risen in recent days, Turkey may be headed for a disaster scenario within the next 10 days unless stricter precautionary measures are taken,” Esen told Arab News.

“There seems to be disagreement within the government between the minister of health and the president. Erdogan reportedly called for a complete lockdown after a recent Scientific Council meeting,” he said.

Turkish government policymakers are believed to be divided on whether imposing a full lockdown is the correct policy.

Minister of Health Fahrettin Koca, along with Scientific Council members under his ministry, advocates strict measures that put public health ahead of other concerns.

There is another group of ministers, however, whose apparent priority is kickstarting the stuttering economy.

“The government has refused to call for a national lockdown and has instead opted for voluntary quarantine and ‘shelter in place’ order for citizens over the age of 65,” Esen said.

“This approach is helping to spread infections if the rapidly rising number of COVID-19 cases is any indication.”

Esen says the government has failed to provide financial relief to low-income citizens, many of whom continue to work in order to earn enough to cover their basic needs.

“Given the weak condition of the Turkish economy even before the pandemic, the government probably does not have sufficient resources to afford a full shutdown,” Esen said.