LONDON: It is never easy to be emotionally detached as one tries to write about one’s alma mater.

But writing about the American University of Beirut (AUB) is a little more difficult, since I regard it as a second home.

Being one of the Arab world’s oldest universities has not shielded AUB from the effects of Lebanon’s unfolding financial, economic and public-health catastrophe.

The situation it is in makes writing about AUB achingly difficult.

Along with my beloved high school, ISC Choueifat, AUB has been part of my family for many decades.

My father, myself, and all my siblings made the same move from Choueifat to AUB.

Furthermore, the first stroll I took with my future wife (an alumna herself) was inside the beautiful AUB campus.

Whenever I am in Lebanon, my stay would never be complete without a lingering visit to the campus; stopping at the departments of History and Arabic in College Hall, the university’s oldest and most iconic building, or the Political Science department in Jesup Hall.

No breathtaking views can compare with the ones looking down from the hilly, charming Upper Campus of the blue Mediterranean and the Green Field in the Lower Campus. This, really, is home.

W.M. Thomson, the prominent American Protestant missionary and author of “The Land and the Book” (published 1859), proposed to a meeting of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, on Jan. 23, 1862, that a college of higher learning should be established in Beirut, with Dr. Daniel Bliss as its president.

Thomson, who spent 25 years in Ottoman Syria, also proposed that the college would include medical training.

According to historical documents, on April 24, 1863, while Bliss was raising money for the new college in the US and the UK, the state of New York granted a charter for the Syrian Protestant College.

The college, which was renamed the American University of Beirut in the early 1920s, opened with a class of 16 students on December 3, 1866.

Daniel Bliss served as its first president, from 1866-1902.

In the beginning, Arabic was used as the language of instruction because it was the common language of the ethnic groups of the region, and prospective students needed to be fluent in Ottoman Turkish or in French as well as in English.

However, in 1887, the language of instruction became English and continues to be until now.

Suliman S. Olayan School of Business. (Courtesy of AUB)

The young university was destined not only to share its fate with the region in which it was founded, but also help shape it.

In its 154 years of existence, AUB has gone through two world wars, famines, civil strife, epidemics, changing maps, as well as economic booms and busts, and all this in one of the world’s most turbulent areas.

It is a mark of the institution’s commitment to excellence in education and promoting intellectual vigor that throughout these years, the AUB alumni, with various specializations, have had a broad and significant impact on the region and the world.

Key Dates

-

1

Daniel Bliss becomes founding president of Syrian Protestant College (SPC).

-

2

SPC settles in Ras Beirut campus, purchased for about $8,000.

-

3

Al-Muqtataf, a monthly Arabic scientific and cultural journal, is launched.

-

4

Professor Edwin Lewis resigns after angering missionary community with his acknowledgment of Charles Darwin as one of the great scientists of his time. Students protest, demanding freedom of speech on campus.

-

5

English becomes main language of instruction in SPC’s medical department.

-

6

AUH, a 200-bed hospital, is built.

-

7

Medical department provides care after Beirut is shelled by two Italian warships targeting Ottoman naval positions in the area.

-

8

SPC medical staff assist relief efforts of the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief during World War I.

-

9

Many starving children, orphaned in the wake of World War I, are cared for at the SPC hospital and the Aintoura Orphanage.

-

10

Eight SPC women establish Women’s League to provide a wide range of social services.

-

11

SPC becomes AUB and grants all professors institutional equality and voting rights within the general faculty, regardless of national origin.

-

12

AUB becomes fully coeducational

-

13

AUB becomes World War II safe haven for residents of surrounding neighborhoods.

-

14

AUB students participate in social protests and force French forces to release prisoners as Lebanon gains independence.

-

15

US First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visits AUB campus.

-

16

Students hold demonstrations in support of Palestinians and Algerians and against Baghdad Pact.

-

17

First open-heart surgery in Lebanon and the Middle East, by Dr. Ibrahim Dagher, performed in AUB.

-

18

Lebanese civil war begins with deadly shooting at a church in East Beirut. Phalangist gunmen respond by ambushing a bus, killing 27 of its passengers.

-

19

An expelled student murders two deans on AUB campus on Feb. 17.

-

20

Summer courses canceled following Israel’s invasion of Lebanon.

-

21

AUB President Malcolm Kerr assassinated outside of his office in College Hall.

-

22

AUB closes after a series of kidnappings of community members.

-

23

Academic program resumes in October after halt forced by civil war violence. Over a 13-month period the medical college treats 23,000 war casualties.

-

24

A bomb destroys a large portion of College Hall, killing an AUB employee.

-

25

AUB announces University for Seniors.

-

26

AUB libraries joins US libraries to create a digital library of more than 100,000 Arabic volumes.

-

27

President Fadlo Khuri announces on March 12 technology-assisted classes to limit the spread of COVID-19.

No less than 19 AUB alumni were delegates to the signing of the UN Charter in 1945; more than any other university in the world.

AUB graduates, Arabs and non-Arabs, continue to serve in leadership positions as heads of states, prime ministers, cabinet ministers, members of parliament, ambassadors, governors of central banks, university presidents and deans of colleges, academics.

Many have become well-known leaders, scientists, engineers, doctors, artists, literary figures as well as prominent employees in governments, the private sector, and non-governmental organizations.

The Lebanese civil war (1975–1990) was another milestone in AUB’s history.

Its medical facilities saved tens of thousands of lives, as it continued to carry out its educational duties in the difficult times.

The AUB pursued various means to preserve the continuity of studies, including enrolment agreements with universities in the US.

Its leadership also strived to maintain the unity, integrity and well-being of the university, by resisting calls to partition it along the sectarian lines of the de facto divided Lebanese capital.

However, despite its unstinting efforts, AUB did not go through the war unscathed.

In 1982, Acting President David S. Dodge was kidnapped on campus by pro-Iranian extremists

Then, on Jan. 18, 1984, President Malcolm H. Kerr was killed outside his office allegedly by members of Islamic Jihad.

In fact, in 1984 and 1985, a number of university staff were kidnapped.

Later in November 1991, a bomb believed to have been set off by pro-Iranian fundamentalists demolished College Hall, the main building of the university, injuring four people, on the 125th anniversary of the school’s founding.

This incident caused widespread anger and spurred the university and its alumni chapters to launch a worldwide fund-raising campaign to rebuild the impressive architectural landmark.

The success of this campaign was crowned by the inauguration of the building in the spring of 1999.

During the last 154 years, AUB has had 16 presidents. The current president is Dr Fadlo Khuri, whose nomination was approved on March 19, 2015, by the university’s Board of Trustees.

He was appointed as AUB’s 16th president on Jan. 25, 2016.

A medical doctor, Dr Khuri graduated from Yale University and Columbia University Medical School and was a professor of hematology and oncology at Emory University.

AUB’s president, Dr. Fadlo Khuri. (Supplied)

Like many presidents before him, Dr. Khuri has a long family association with AUB. His paternal grandfather was an early alumnus, his late father, Dr. Raja Khuri, was a dean of the School of Medicine, and his mother, Sumayya Khuri – now retired – was a professor of mathematics.

In the fall of 2018, there were over 9,000 students enrolled at AUB: 7,180 undergraduates and 1,922 graduate students, studying at the university’s seven faculties, namely:

* Agricultural and Food Sciences.

* Arts and Sciences.

* Health Sciences.

* Medicine.

* Rafic Hariri School of Nursing.

* The Maroun Semaan Faculty of Engineering and Architecture.

* The Suliman S. Olayan School of Business.

For a while, AUB also had a Dental School and a School of Pharmacy, but they were later discontinued.

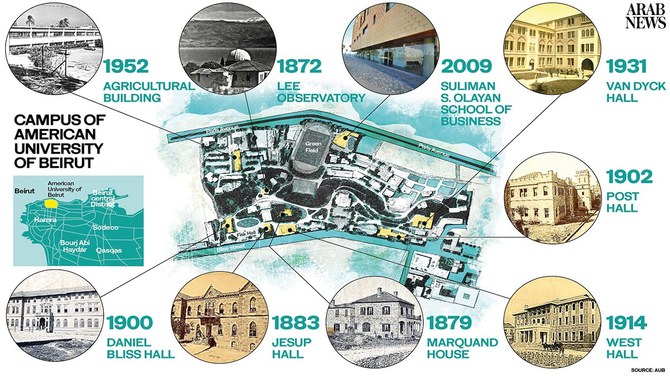

All the existing faculties are located in the university campus of 61 acres, which has 64 buildings, including a highly renowned medical center.

Furthermore, the university owns and operates a 247-acre research farm and educational facility in the Bekaa Valley in eastern Lebanon.

The main Ras Beirut campus is situated on a hill overlooking the Mediterranean Sea on one side and bordering Bliss Street on the other.

------

READ MORE: AUB president says liberal Arab thought at risk amid Lebanon’s coronavirus, financial crises

------

Among its 64 buildings are seven dormitories and several libraries.

In addition, the campus houses the Charles W. Hostler Student Center, an observatory, an Archaeological Museum as well as the widely renowned Natural History Museum.

The AUB Medical Center (AUBMC) is the private, not-for-profit teaching center of the Faculty of Medicine. AUBMC includes a 420-bed hospital and offers comprehensive tertiary/quaternary medical care and referral services in a wide range of specialties and medical, nursing, and paramedical training programs at the undergraduate and post-graduate levels.

Throughout its history, the AUB Medical Center, which was formerly known as the American University Hospital (AUH), has played a critical role in caring for the victims of regional and local conflicts.

It provided care for the sick and wounded during World War I and World War II, the Lebanese War, the Palestinian conflict, and the invasion of Iraq.

In recent years, it has provided care for a number of Syrian refugees at the Medical Center in Beirut, at partner hospitals, and at mobile clinics.

In 2008, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) invited AUB’s Rafic Hariri School of Nursing to become a full member, making it the first member of the AACN outside the US.

AUBMC is the first healthcare institution in the Middle East and the third in the world outside the US to receive this award.

In his inaugural address in January 2016, Khuri affirmed AUB’s commitment to be the regional leader and a key global partner in addressing global health challenges.