BEIRUT: Over the past 10 years, the commercial landscape of the Middle East and North Africa has undergone a gradual but radical change. Gone are the days when goods from the West filled the shelves of corner shops and supermarkets. They now stock the full gamut of Chinese-made products, from cellphones to air-conditioners and from school stationery to washing machines.

Few countries in the region exemplify China's emergence as a competitor to the West's global manufacturing dominance as clearly as Lebanon, with its economy in tatters and foreign currency reserves exhausted.

When the first case of COVID-19 was recorded on February 21 in Lebanon, Chinese authorities rushed to deliver medical assistance to the government.

The promptness of the response created the impression in some circles that China was seeking to gain a strategic foothold in Lebanon, which had long been viewed as a political playground for major powers and the Middle East’s gateway of sorts to the West.

A call sounded by the Hezbollah chief, Hassan Nasrallah, in November last year, and repeated a few weeks ago, to “go to China to save Lebanon financially and economically,” has left many wondering whether Lebanese politicians are aligning their country too closely with the Asian power.

Even by the standards of the calamities that struck it in the 20th century, Lebanon has never been more vulnerable than it is now amid the coronavirus crisis.

The economy is projected to shrink by 12 percent this year, while half the government’s budget will go to service a debt burden that has reached 170 percent of GDP. The share of Lebanon’s population below the poverty line is believed to have jumped to 75 percent from the pre-pandemic level of 50 percent.

Armed Forces guard a demonstration against the poor economy. Analysts fear poor economic conditions make Lebanon ripe for exploitation. (AFP)

Against this grim backdrop, some Lebanese politicians, economists and academics are arguing that Beirut has lagged behind other countries in strengthening ties with Beijing, just as it was late in giving diplomatic recognition to the Communist-led People’s Republic of China.

“Lebanon recognized the People’s Republic of China only after Henry Kissinger’s secret trip to the country in 1971,” said Dr. Massoud Daher, head of the Chinese-Lebanese Friendship and Cooperation Committee, referring to the former US secretary of state and national security adviser.

Nearly 50 years on, it seems the shoe is on the other foot.

In the last week of May, the People’s Liberation Army made a direct donation to the Lebanese Army to boost the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. The items included surgical face masks, goggles, protective clothing and other medical supplies.

The coronavirus gear was handed over as part of an agreement that was signed by Wang Kejian, China’s ambassador to Lebanon, and General Joseph Aoun, the Lebanese Army Commander.

“The Chinese donation clearly reflects the solidity and depth of the relationship between the two peoples and the two armies,” Wang said.

“China is ready to work with the Lebanese people and army to overcome the difficulties and troubles. After all the difficulties and obstacles have been cleared, new roads and horizons will open up.”

China's military donated to the Lebanese Army medical supplies needed in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. (Xinhua photo)

By contrast, in an op-ed last month that appeared to encapsulate the view from Washington, Danielle Pletka, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, wrote: “While the Islamic Republic of Iran is still calling the political shots, vultures from Beijing are circling, eyeing tasty infrastructure assets like ports and airports as well as soft power influence through Lebanon’s universities. Meanwhile, Lebanon as a sovereign nation collapses.”

China of course has also a longstanding military presence in Lebanon, in the form of a 410-strong unit serving with UNIFIL in the country’s south.

The soldiers of the unit perform operational and humanitarian duties involving medical services, disposal of unexploded ordnance, construction of UNIFIL protection facilities, road building and rehabilitation of schools and kindergartens in the border areas.

The Chinese Field Hospital at the UNIFIL headquarters, north of Marjeyoun, provides a range of medical services to local residents and to UNIFIL soldiers.

Even before the coronavirus aid started arriving, relations between Lebanon and China were warming, with the latter doing all the giving as part of its “soft power” projection.

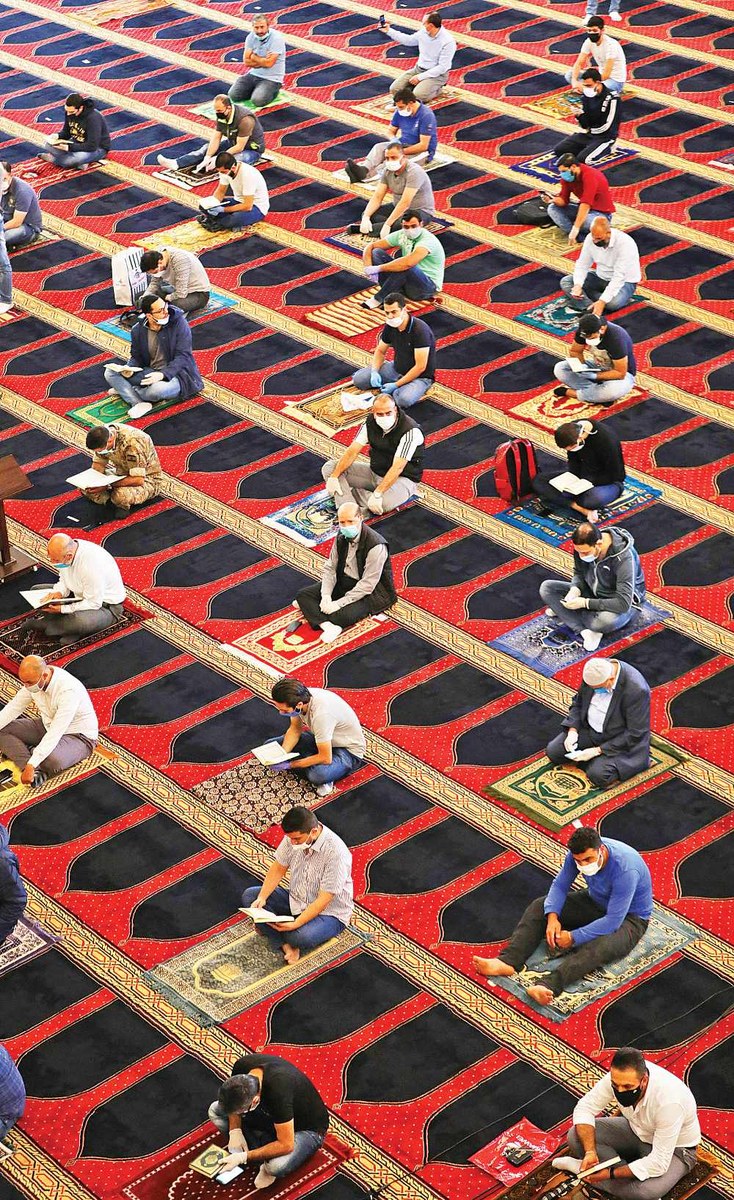

Worshippers perform prayers during Ramadan while keeping a safe distance at a Mosque in Beirut. (AFP)

Last year, a delegation of Chinese businessmen visited Lebanon and held meetings away from the media gaze, during which they offered to fund a number of projects.

These included the Arab highway linking Beirut to Damascus and a parallel railway project connecting Beirut first to Damascus and then to China’s $900 billion new Silk Road, the trade corridor designed to reopen channels between China and countries of Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe.

The Chinese visitors also offered to construct highways going from Lebanon’s north to south and build solar power plants that would generate electricity at affordable rates.

Just last month, China signed a cooperation agreement with Lebanon aimed at establishing cultural centers in the two countries “on the basis of equality and mutual benefit.”

According to the agreement, signed by Ambassador Wang and Abbas Mortada, Lebanon’s Culture Minister, on behalf of their governments the centers will provide a “wider platform for cultural exchange and mutual learning between the two countries.”

In April, the Lebanese Ministry of Health received a donation consisting of protection gear and COVID-19 testing kits, given as part of Beijing’s “donation diplomacy.”

February saw a number of online training workshops conducted by Chinese doctors aimed at raising awareness of coronavirus risks among medical workers and volunteers in community clinics in Lebanon’s refugee camps.

About 80 percent of Lebanon’s needs are met through imports and, according to China’s state-run Xinhua news agency, 40 percent of the imports come from China.

The gross value of imported Chinese goods — typically electrical appliances, clothing, toys, cellphones, furniture, industrial equipment, candies and foodstuff — is estimated at $2 billion annually.

The trade imbalance is evident from Lebanon’s annual exports to China, which amount to no more than $60 million.

Lebanon’s Culture Minister Abbas Mortada (2nd left) and China's Ambassador Wang Wang Kejian (2nd right) signing a cooperation agreement last month in Beirut. (Xinhua photo)

The influence of China can be gauged from social trends as well. In recent years, Lebanon has seen a growing interest among young people in learning Chinese.

Among other academic institutions, the Confucius Institute at St. Joseph’s University in Beirut and the Language Centre at the Lebanese University have Chinese language programs.

“Until 2003, Lebanon and China had only formal political relations,” Daher told Arab News, noting that in 1978 China adopted a policy of openness and reform as well as signaled its intent to expand its influence abroad in order to promote its industry.

“In 2006, we established the Chinese-Arab Friendship Association (CAFA). Since then, we have held more than 15 conferences sponsored by China in various disciplines in 23 Arab countries. The number of Lebanese merchants who have visited China stands at 11,000.”

According to Daher, China has signed four agreements with the Lebanese University and another with the Ministry of Culture.

“China had to wait for three years to be granted the permit to build its cultural center in Lebanon,” he said.

“The Chinese donated $66 million to set up Lebanon’s largest music center, currently being built by Chinese companies. The Lebanese state has only provided the land.”

Daher believes “the Chinese are taking the long view,” with the Lebanese economy and the military as well as the banks still tied to American institutions.

He dismisses the notion that China is seeking to gain control over Lebanon’s political and economic decision-making structures.

“China is not being able to get into Lebanon. Entry even through investment projects will be difficult since the Lebanese ask for their cuts, but the Chinese, like the Japanese, do not pay bribes from government money.”

Pointing to the interest reportedly expressed by Chinese firms to take over electricity and infrastructure projects in Lebanon, he said “the offers have not been approved, and China is forbidden from entering Lebanon in such ways.”

Daher puts it this way: “China is interested in marketing its products in such a way that both parties can benefit from. Lebanon is an economically distressed country and does not constitute an important market for China.

“The problem is that the money of the Lebanese people is blocked in banks and the economy is in recession. China sells us its products at attractive prices, but how can the products be marketed in a country whose purchasing power is declining on a daily basis?”

Still, with tensions between China and the US rising over Beijing’s donation diplomacy in the latest of many disputes, Zhang Jian Wei, director general of the Department of West Asia and North Africa at the International Liaison Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, said: “We do not intend to replace the United States in Lebanon and we do not have the capacity to do so because China is still a developing country. Even if China becomes more developed economically, it will not seek to fill any vacuum in Lebanon.”

Wei hinted that China’s cooperation with Arab countries is bothering some countries, such as the US, which “is taking all measures to contain China’s influence.”

“The US is the largest developed country in the world, with which we do not want a trade war. But if the American insisted, we will fight it till the end,” he said.

For all the deepening, multidimensional ties with China, Daher says Lebanon is tied to the US until further notice.

“It can neither open up to China, nor free itself of American influence,” he said.

“Since the political class is capitalist, rentier and sectarian by nature, it sticks to quotas and avoids reforms.

“If Lebanon decides to change for the better, then it must open up to China. If the situation remains the same, Lebanon will go bankrupt.”

----------------

@najiahoussari