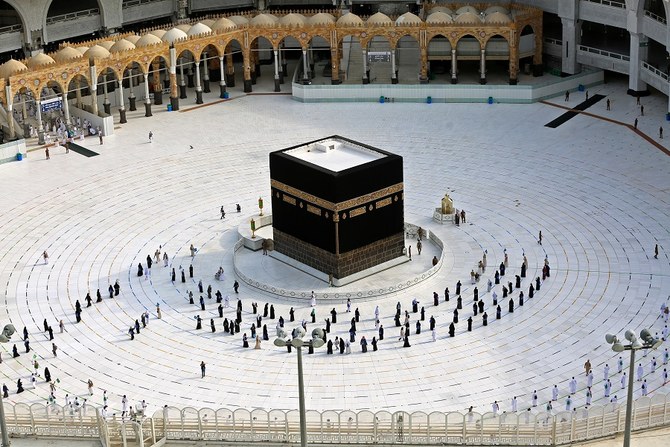

Of all the extraordinary images beamed around the world from this year’s unprecedented Hajj, it was the time-lapse footage of pilgrims circumambulating the Kaaba with carefully choreographed, socially distanced precision that best captured the spirit of Saudi Arabia’s determination to tackle the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic effectively, efficiently and on its own terms.

With responsibility for the health of the millions of pilgrims who visit each year, and by extension for the wellbeing of the nations from which they come, it was clear from the start of the pandemic that Saudi Arabia was not going to take any chances with its management of the fifth pillar of Islam.

On Feb. 27, before a single case of COVID-19 had been detected in the Kingdom, Saudi Arabia announced it was suspending overseas visitors’ visas for Umrah, the lesser pilgrimage, and closing the holy sites to foreigners.

On March 17, Saudi Arabia took the unprecedented but necessary step of temporarily closing all places of worship but for the Two Holy Mosques in Makkah and Madinah. Three days later, these too were shut.

Meanwhile, Muslims around the world waited anxiously to see how the Kingdom would manage Hajj in this most extraordinary of years. It seemed impossible that Hajj would not go ahead in some form, but much was at stake.

In 2019, 2.5 million pilgrims converged on Makkah for Hajj, among them 1.85 million from overseas, and the prospect of potentially sending large numbers home with the virus to dozens of countries around the world was unthinkable.

In the end, Saudi Arabia settled on a historic compromise.

On June 23, the government announced that Hajj would go ahead, but with only a “very limited” symbolic number of pilgrims allowed to take part, a decision taken in consultation with a number of other countries whose governments had decided to cancel their Hajj missions in light of the pandemic.

In a statement, Dr. Mohammed Saleh Benten, minister of Hajj and Umrah, said the decision had been taken to limit numbers to just 1,000 pilgrims, chosen from among people who were already resident in the Kingdom, aged under 65 and free of serious health problems.

Qualified medical personnel would accompany small groups of pilgrims, each one of whom would be tested for COVID-19 before arriving at the holy sites, would wear an electronic tracking bracelet while performing Hajj and be subject to self-isolation afterwards.

Face masks would be mandatory, only pre-bottled Zamzam water could be drunk and even the pebbles used for the symbolic stoning of the devil, normally collected from the ground at Muzdalifah by the pilgrims themselves, would be gathered for them beforehand, sterilized and issued in bags.

Throughout Hajj, 51 clinics, five hospitals and a mobile medical unit were ready to treat pilgrims, with no fewer than 200 ambulances and thousands of healthcare professionals on standby.

The Grand Mosque itself has been cleaned 10 times a day during the pandemic crisis.

On the eve of Hajj, at the 45th Grand Hajj Symposium on July 28, Benten said the Kingdom was “keen to ensure that the fifth pillar of Islam is performed in a secure, healthy and safe manner, along with the great care of those who will be able to attend and perform Hajj.”

Sheikh Abdulrahman Al-Sudais, the head of the Presidency of the Two Holy Mosques, stressed the importance of “abiding by the preventive instructions and measures adopted by the government, which include … paying attention to medicine and mental health, warning against myths and working to implement the Prophet’s hadith.”

For Islamic Affairs Minister Sheikh Abdullatif Al-Asheikh, the wisdom of the Islamic Shariah attached “great importance to the safety of worshippers and seeks to protect them from any harm while praying and performing their religious duties.”

Saudi Arabia’s long experience of imposing strict protective measures to guard pilgrims against the possibility of contagious diseases helped to ensure that 2020 passed off without a hitch. In 2019, for example, when 2.5 million pilgrims performed Hajj, there were no public health issues.

In the end, not a single case of COVID-19 emerged during Hajj, a public health victory for the state that belonged also to the pilgrims, whose behavior and adherence to the new rules was exemplary.