RAWALPINDI: Nigar Nazar, Pakistan’s first female cartoonist, whose famed character Gogi was first published in 1970, says lack of opportunities on traditional platforms like newspapers and magazines had pushed many of the country’s emerging cartoonists, and a pioneer like herself, to self-publish or turn to social media.

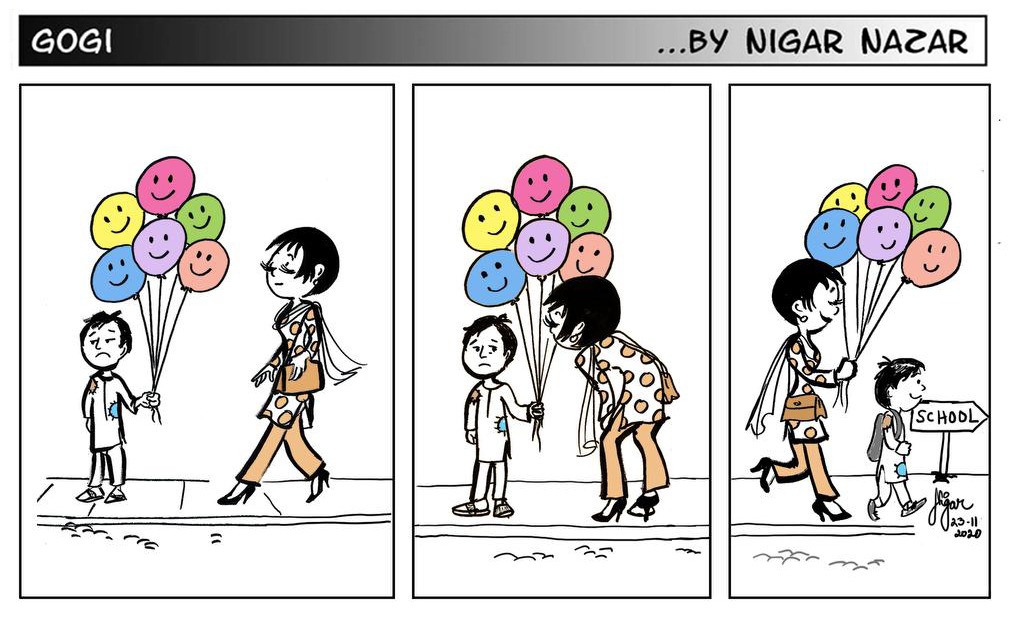

The much-loved Gogi character, a progressive, educated Pakistani woman who wears polka-dotted dresses, has been Nazar’s mouthpiece for decades to speak about social issues and contradictions in society.

But now, the cartoonist said, “whenever I have something I want to say about society, or what is happening, I publish on my own social media.”

A comic strip for International Children's Day of Gogi, a character created and drawn by artist Nigar Nazar on November 24, 2020. (Photo courtesy: Gogi Studios/Facebook)

“What the newspapers could have been doing for their contributors is support the form of cartoons,” Nazar said in a phone interview on Wednesday. “Majority are not. I don’t see any jobs with newspapers for cartoonists and even illustrators — even for people like me, whose work has been there for a long time.”

Nazar, who said she hasn’t been published on a traditionI platform for a “long time now,” has moved to making cartoons for hospitals and on public buses.

“And I am doing books now, and I’m doing programs for, you know, creative art and craft programs on my YouTube channel. So that’s what I moved on to,” she said. “When I do get affected by the existing current affairs or situations which are not necessarily political, you know social, socio-economic, then I do make comic strips and publish them on my own social media.”

“It’s a very lonely industry,” she added.

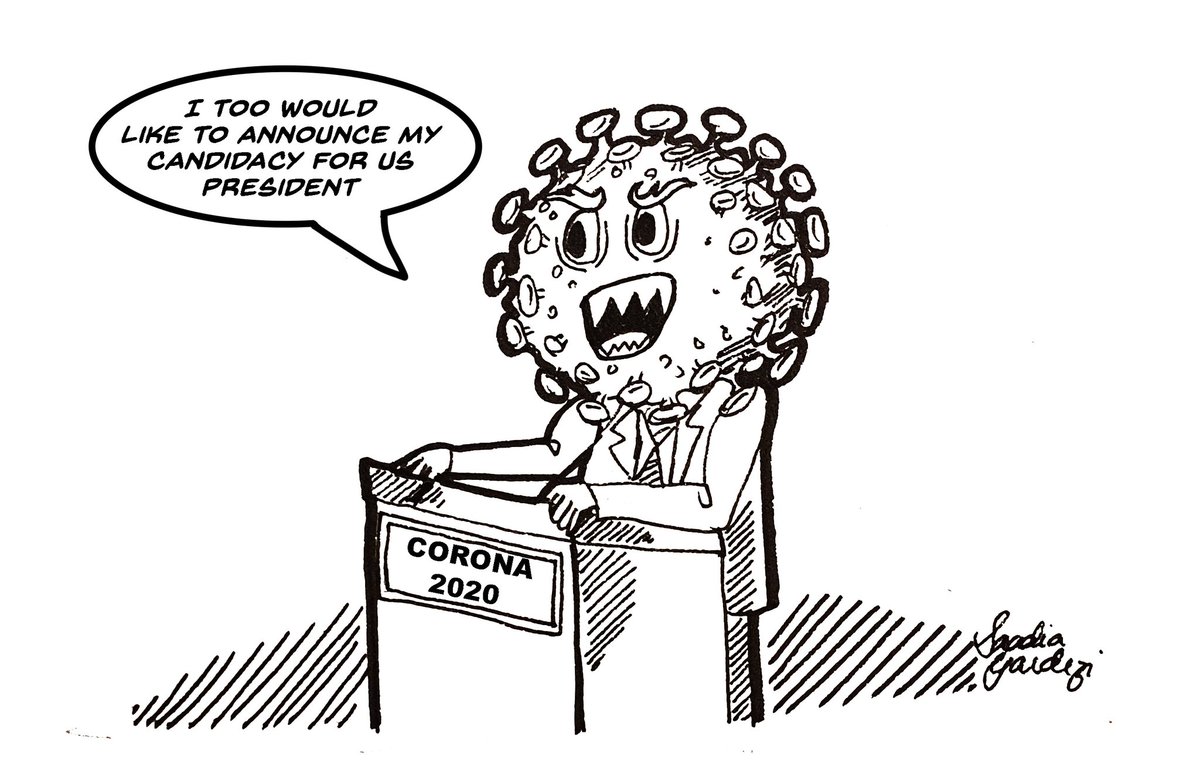

Saadia Gardezi, the editorial cartoonist for The Nation newspaper, said she was glad many of her colleagues still had jobs at traditional platforms “even as we are seeing greater digitization.”

“I do think it is a narrowing field that is not attractive to young artists because of the high demand from work and meager salaries, more so than because of a lack of adaptation to digital formats,” Gardezi said.

This caricature of the coronavirus is drawn by the cartoonist, Saadia Gardezi, on July 14, 2020 (Photo courtetsy: Saadia Gardezi/Twitter)

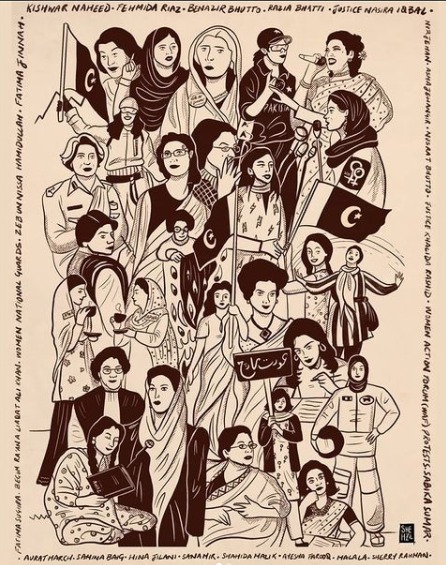

Shehzil Malik, one of Pakistan’s most recognizable digital artists, said because so many people were using social media now, it had become the choice platform for many artists, including cartoonists, to try to find an audience.

“There are Pakistani women artists on Twitter with massive followings because they regularly post art on what they’re into — it could be anime or their original characters — and find a fan base,” Malik told Arab News.

Another bonus for women cartoonists and digital artists, she said, was that social media gave them the option to often remain anonymous when speaking about taboo topics like divorce and abuse that often rankle hard-liners and conservatives.

This undated illustration, drawn by Shehzil Malik, shows famous female icons of Pakistan. (Photo courtetsy: Shehzil Malik/Instagram)

“Digital platforms are without traditional gatekeepers like in art circles and galleries,” said Malik. “We [digital artists] don’t have physical spaces to exhibit illustrations or what is thought of as ‘low brow’ or not ‘fine art’.”

But she said this was changing, and social media had helped to “democratize” the field.

Karachi journalist Reem Khurshid, 34, an editorial cartoonist for Dawn, also said social media was an equalizer.

“These platforms did not exist when I was first starting out, everything was much more limited,” Khurshid told Arab News over the phone. “This new digital world allows for building communities within your country, your city, and outside of it. I think it’s been really good in terms of sort of challenging mainstream culture through a feminist perspective.”

This picture shows a cartoon on 'fake news', sketched by Reem Khurshid on December 6, 2020. (Photo courtesy: Dawn)

While Khurshid works in both the print medium and social media, she said “the online is fast becoming the place for cartoons and comics from Pakistan to thrive.”