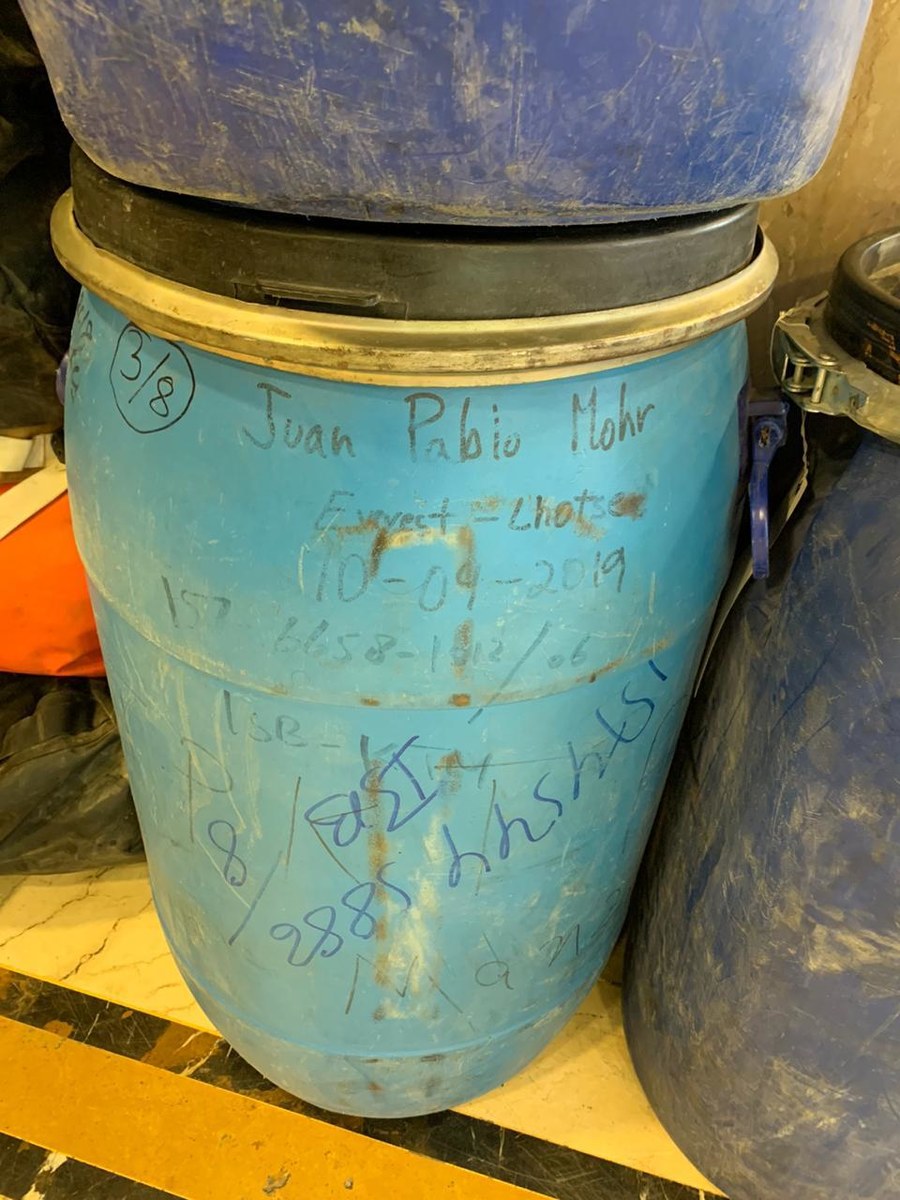

ISLAMABAD: In the lobby of a small downtown hotel in the Pakistani capital of Islamabad, a stack of odd-shaped luggage lined along a wall on Saturday morning was nothing out of the ordinary at first glance. On closer inspection, the words “JP Mohr” could be seen scrawled in black on a number of blue porter's drums, a familiar part of treks through Pakistan's high mountains.

The 33-year-old Chilean mountaineer Juan Pablo Mohr is one of three climbers who went missing on February 5 during a historic push to summit K2 in winter - one of mountaineering’s last great feats, achieved for only the first time in history this year by a group of Nepali climbers.

The arrival of Mohr's belongings in the capital over a week after he went missing coincided on Saturday with his two concerned relatives flying into Pakistan from Chile, saying they had been sent by the climber's immediate family to 'bring JP back,' as an arduous helicopter rescue mission continues the search to find him, Pakistan's Ali Sadpara and Iceland's John Snorri.

"The family told us directly... we must come back with JP," Federico Scheuch, Mohr's manager and cousin, told Arab News in Islamabad.

Federico Scheuch (left), manager and cousin of missing K2 climber JP Mohr, and Mohr's childhood best friend Juan Pablo Diban, speak to Arab News in Islamabad, Pakistan on February 13, 2021 (AN Photo)

"The family has a lot of hope and we are waiting for the miracle," he said, adding that he would be flying to the northern town of Skardu the following morning, Sunday, so he could be "closer" to information about ongoing search and rescue attempts.

Back home, Scheuch described a country paralyzed with news of Mohr’s disappearance, with Chileans hoping against hope that one of the pioneer’s of the nation’s mountaineering culture would be found alive on the treacherous K2, the world's second highest mountain.

"We're here for the Chilean people... for hope," he said.

In this photo taken on February 13, 2021, the luggage of Chilean mountaineer Juan Pablo Mohr can be seen in the lobby of a hotel in Islamabad, Pakistan. Mohr is one of three climbers who went missing on February 5 during a historic push to summit K2 in winter (AN photo by Amal Khan)

"The bag just came back from Skardu and I don't want to open it," Scheuch added. "It's scary... it's part of JP... all the things that are in there."

From Skardu, his voice breaking over the phone, Sadpara's son and expedition member Sajid Sadpara told Arab News hope for a positive recovery had all but faded.

"They're saying the rescue operation is still underway up there... but hope is now close to gone," Sadpara said. "My mother is broken-hearted. She is so sad.”

In this photo taken on February 13, 2021, at a hotel in Islamabad, Pakistan, a porter’s drum can be seen with the words “JP Mohr” written on it - part of the recovered luggage of Chilean mountaineer Juan Pablo Mohr. Mohr is one of three climbers who went missing on February 5 during a historic push to summit K2 in winter (AN photo by Amal Khan)

Sajid was the last person to see the three climbers make their final push to the summit on Friday (February 5) morning, at what is considered the most difficult part of the climb: the Bottleneck, a steep and narrow gully just 300 metres shy of the 8,611 metre high K2.

From there, Sajid, whose oxygen regulator malfunctioned, was asked by his father to climb back down. He made his way to Camp 3 and waited for over 24 hours for the team to descend. They never did.

"We are trying to be the first line of information," Juan Pablo Diban, Mohr's childhood best friend, told Arab News in Islamabad. "We've been watching the news all of last week, talking with anyone who can give us information,” he added, saying him and Scheuch had come to Pakistan "to get more answers."

Diban described Mohr, a father of three, as someone who could never still ever since he was a child and who was always joking and making others around him laugh. He was also hugely respected back home for his social work.

"The whole of Chile is paralyzed by this news," Diban said. "JP is so much of a giver. He gives happiness to a lot of people."

Speaking about Mohr's decision not to carry supplemental oxygen - the only one in the group not to do so - Diban and Schuech called him a mountaineering purist who just liked doing things the old-fashioned way.

"He preferred to...summit without oxygen. He didn't use sherpas (porters) ... if he can help it, he doesn't use ropes," Schuech said.

"He just wanted to do it that way for the pureness of the sport," Diban added.

Then he laughed softly: "We also don't want to open his bags... because he is so messy.”