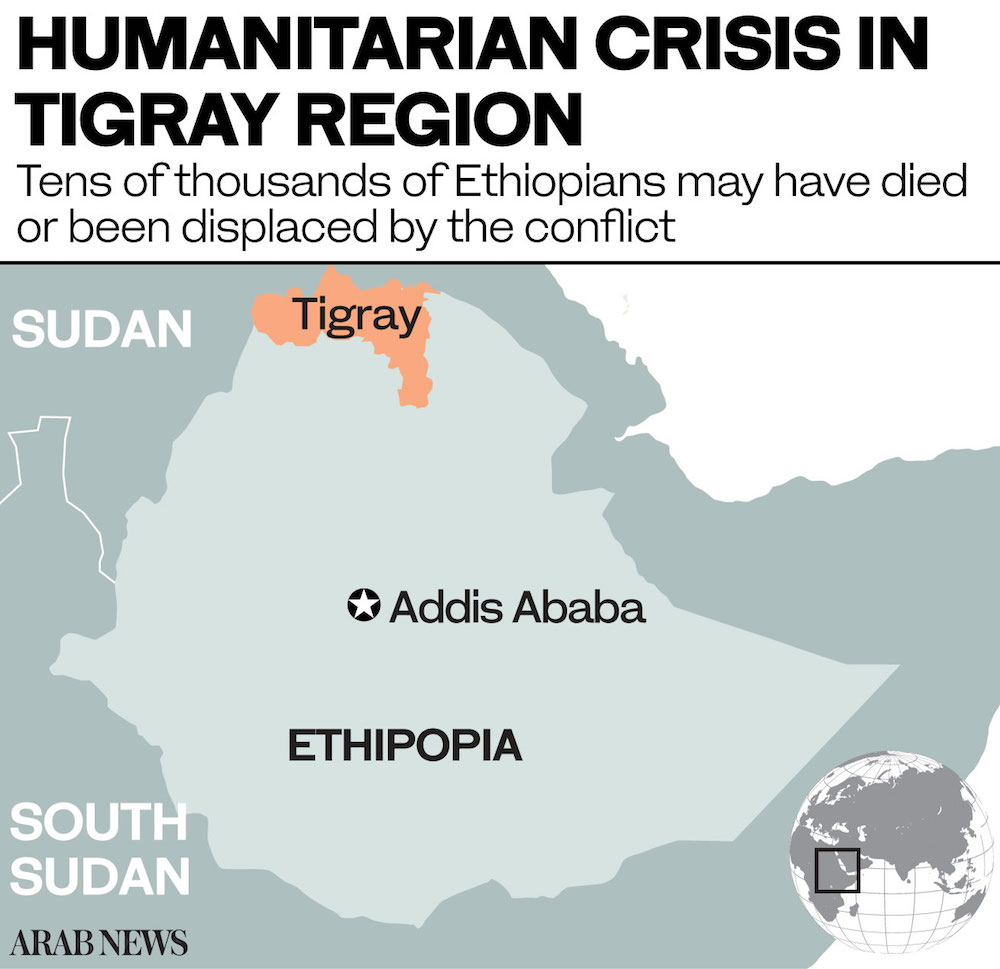

DUBAI: With their few hurriedly packed belongings wrapped tightly in fabric, entire families, many with young children, are traversing vast distances on foot these days to escape fighting in northern Ethiopia between federal armed forces and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF).

Since the conflict erupted three months ago, nearly two million Ethiopians have been forced to flee the country’s Tigray region, many arriving in neighboring Sudan with axe and knife wounds, others with broken bones and severe mental trauma.

Those who have chosen to stay behind — the vast majority of Tigray’s six million inhabitants — now face shortages of food, medicine and drinking water. Ethiopia is facing accusations of blocking aid and the specter of mass hunger haunts the region.

Most concerning of all is the imminent risk of mass hunger, a phenomenon Ethiopians are tragically familiar with. The Great Famine that afflicted the country between 1888 and 1892 killed roughly one-third of its population. Another in 1983-85 left 1.2 million dead.

According to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network, presided over by the US government, parts of central and eastern Tigray are just a step away from famine, with fears more than a million could die of starvation if aid is not allowed in soon.

In a recent statement, a trio of Tigray opposition parties said that at least 50,000 civilians had been killed in the conflict since November. Aid agencies and journalists have not been permitted access to the region to verify the death toll.

Ethiopian authorities insist aid is being delivered and that nearly 1.5 million people have been reached. But experts on the Horn of Africa believe one of the worst humanitarian disasters in modern history is unfolding in the conflict zone.

“If the world averts its eyes, it is a bystander to one of the most grievous mass atrocities of our era,” Alex de Waal, executive director of the World Peace Foundation and a research professor at The Fletcher School at Tufts University, told Arab News.

“It will be an unforgivable ethical stain. It is also a matter of interest. Do the countries of the Arabian Peninsula want to see another Yemen-like calamity on the southern shores of the Red Sea — a little further away, but even bigger?”

Abiy Ahmed, Chairman of Oromo Peoples' Democratic Organization (OPDO) looks on in Addis Ababa. Spearhead in the fight against the Derg dictatorship, then a real power in Ethiopia for a long time, the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), which the Ethiopian army fights in its northern stronghold of Tigray, has shaped recent history of the country. (AFP/File Photo)

The TPLF, which had dominated Ethiopian politics after the fall of the military dictatorship in 1991 until Abiy’s election victory in 2018, had been in coalition with the current government until the two sides fell out in 2019.

In direct defiance of the federal government’s decision to postpone all votes until the COVID-19 pandemic was under control, Tigray authorities pressed ahead with their own parliamentary election in September. Federal authorities said the vote was illegal.

Tensions escalated further in November when Abiy accused the TPLF of seizing a military base in the regional capital Mekelle. His government responded by declaring a state of emergency, cutting off electricity, internet and telephone services, and designating the TPLF as a terrorist organization.

Although Abiy claimed victory when federal troops entered Mekelle on Nov. 28, the bloodshed has continued as Tigrayan leaders have vowed to fight on.

“The federal government called the conflict a law enforcement operation (intended) to remove from office the Tigray region’s rogue executive,” William Davison, International Crisis Group’s senior analyst for Ethiopia, told Arab News.

“The reality was that Tigray’s defenses were overwhelmed by the full power of the Ethiopian federal military and allied forces.”

UN REPORT HIGHLIGHTS

* Reports from aid workers on the ground indicate rise in acute malnutrition across Tigray region.

* Only 1% of the nearly 920 nutrition treatment facilities are reachable.

* Aid response is drastically inadequate, with little access to rural population off the main roads.

* Some aid workers have to negotiate access with armed actors, even Eritrean ones.

As the campaign got underway, the Ethiopian government presented the TPLF as a treasonous entity that had attacked the military and violated the constitutional order, saying that it had no choice but to act.

It also moved against those who questioned whether the intervention would be as quick and painless as claimed, such as Davison, who was deported on November 20.

Ethiopian refugees who fled intense fighting in their homeland of Tigray, gather in the border reception centre of Hamdiyet, in the eastern Sudanese state of Kasala, on November 14, 2020. (AFP/File Photo)

Abiy, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for restoring relations with Ethiopia's long-time foe Eritrea, is now being accused by some of war crimes in Tigray.

Seyoum Mesfin, a former Ethiopian foreign minister, peacemaker and an elder statesman of Africa, was among three TPLF leaders killed by the military in early January in a move that sparked an international outcry.

Pramila Patten, the UN envoy on sexual violence in conflict, has said there are “disturbing reports of individuals allegedly forced to rape members of their own family, under threats of imminent violence.”

Recently, the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission said 108 cases of rape had been reported over the last two months in the whole of Tigray. It admitted that “local structures such as police and health facilities where victims of sexual violence would normally turn to report such crimes are no longer in place.”

A medic disinfects his tools inside a medical facility for Ethiopian refugee who fled fighting in Tigray province at the Um Raquba camp in Sudan's eastern Gedaref province, on November 21, 2020. (AFP/File Photo)

All this amounts to a sharp reversal of fortune for a country that just months ago was being feted as Africa’s fastest growing economy. Now, Ethiopian journalists and human-rights activists are afraid to speak out, many of them avoiding the border areas and letting military atrocities go unreported.

“We’ve been on our toes for months now. You need to be very careful with your comments,” one Addis Ababa-based political analyst, who did not wish to be identified, told Arab News.

“Human-rights abuses are being committed on all sides: the Amhara militias (one of the two largest ethnic groups in Ethiopia), the federal troops themselves and the Eritreans too.

“The humanitarian aspect of the conflict is frightening and especially the lack of indication from the government’s side in providing aid. They say they will, publicly. But large sections of Tigray are still inaccessible. It’s very difficult to say how long they intend to keep it this way, which is of great concern.”

A member of the Amhara Special Forces holds his gun while another washes his face in Humera, Ethiopia, on November 22, 2020. Prime Minister Ahmed, last year's Nobel Peace Prize winner, announced military operations in Tigray on November 4, 2020, saying they came in response to attacks on federal army camps by the party, the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF). (AFP/File Photo)

Eritrean soldiers have compounded the problem by reportedly attacking the TPLF on behalf of Abiy’s government, prompting calls from Joe Biden’s administration for their immediate withdrawal. (Both Asmara and Addis Ababa deny that Eritrean forces are present in Tigray.)

Reports say many of the estimated 100,000 Eritrean refugees residing in the region are at risk of getting caught in the crossfire or being forcibly returned. Filippo Grandi, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, has said he is “deeply alarmed by reports of refugees being killed, abducted and forcibly returned to Eritrea that would constitute a major violation of international law.”

De Waal of the World Peace Foundation says if the war causes a humanitarian catastrophe and the economic collapse of Ethiopia, there is no doubt that the consequences will be felt far and wide.

“The human and economic price will be paid by the people of the Horn of Africa, but those people will also start moving en masse towards Europe, and the humanitarian cum economic bailout bill will be presented to Europe and the US,” he told Arab News.

“At a time of austerity and reduced aid budgets, this presents aid donors with a terrible dilemma.”

Summing up the Tigray crisis and its potential solution without mincing words, De Waal said: “With every passing day there is more suffering, killing, starvation, deeper bitterness and wider repercussions. Withdraw Eritrean troops. Then start political talks.”

----------------------

Twitter: @rebeccaaproctor