RIYADH: Once upon a time, mankind produced a small amount of waste. Food was not packaged, fruit and vegetable peelings were fed to animals and the dung from horses and camels was used for fertilizer or dried and burned for heating. Most of what came from the earth went directly back into the earth with little or no harm to the environment.

Today, we live in a consumer age in which multitudes of products are purchased and the ensuing trash disposed of with little or no regard for its detrimental impact. Many single-use goods are manufactured and distributed at considerable expense, only to be momentarily used and then thrown away forever.

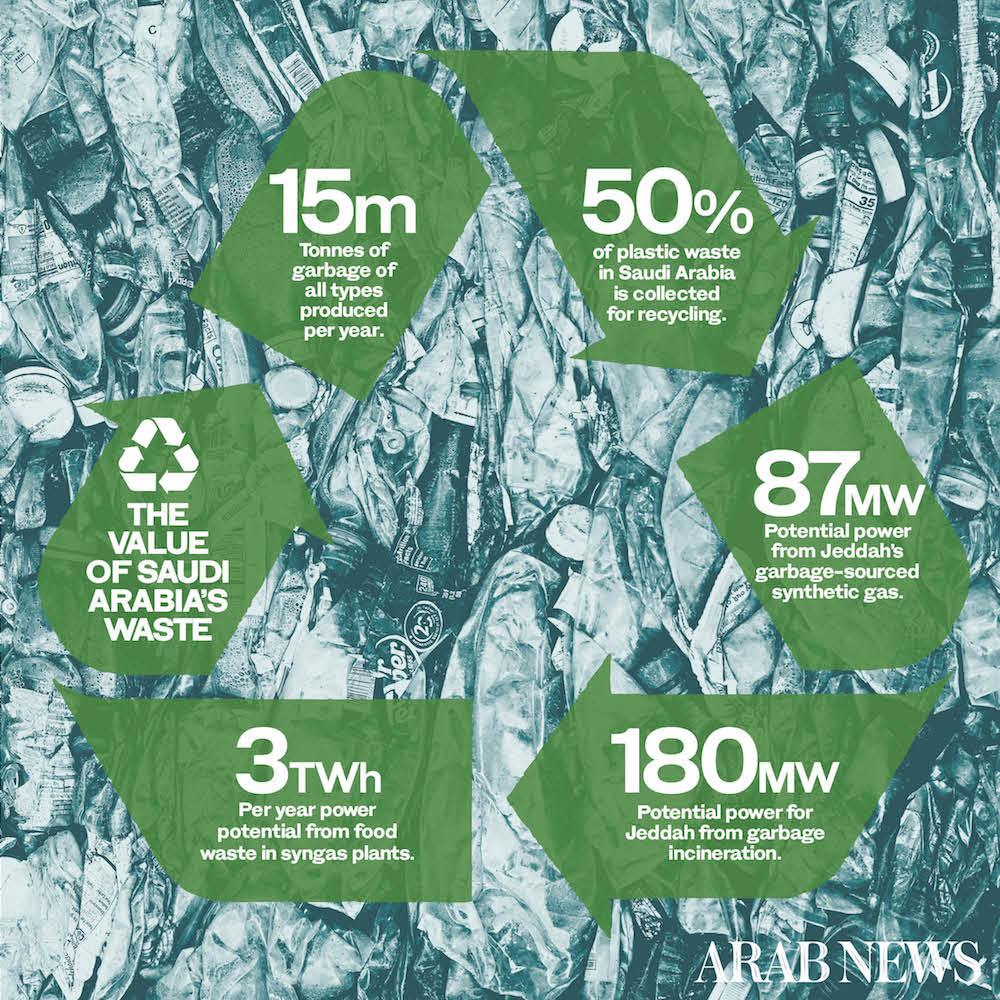

Saudi Arabia produces no less than 15 million tons of garbage per year — most of which ends up in giant landfills, full of dangerous toxins that seep deep into the ground.

Fortunately, there are now signs of a sea change, both in the Kingdom and around the world. An emerging concept known as “the circular economy” holds that any form of solid waste can be the raw material for a new and more valuable resource.

This is a contemporary answer to alchemy — the medieval quest to turn base matter into gold.

The circular economy involves both upcycling (the process of transforming waste materials into products of greater value) and downcycling (whereby discarded material is used to create something of lower quality and functionality).

Plastic is an obvious starting point. Heralded as a miracle substance almost a century ago, it became ubiquitous in our groceries, clothing, cars and electronic devices.

That initial enthusiasm for plastic has gradually led to a sober realization that it takes up to 500 years to decompose — presenting an environmental calamity that we witness daily on streets littered with plastic bags, cups, bottles and straws.

But did you know that some 50 percent of the plastic waste in Saudi Arabia is collected for recycling?

Plastic bottles before they are recycled. (AFP/File Photo)

Once cleaned and processed, this used plastic can be transformed into pellets, which in turn are melted down to form anything from household tiles to benches to roadside curbs. Japan is the leader in this respect, now recycling almost 90 percent of its plastic waste.

In fact, it is normal in Japan for households to have over half a dozen different containers for various kinds of trash, to ease sorting for recycling purposes.

India’s Kerala Highway Research Institute has developed a recycled, plastic-derived road-surfacing material that is more durable than conventional tarmac and able to withstand the heavy monsoon rains.

Household waste can also produce the energy needed to heat homes and charge electric cars of the future.

As organic matter (that is, anything from apple cores to onion skins) decomposes, it produces methane gas — a source of energy. Other solid waste — for example, cardboard and wood — can be incinerated, again to provide energy.

These processes are collectively known as “waste-to-energy” (WtE). Methods also exist for the filtration of the resulting fumes, reducing carbon output from WtE to almost zero.

A sanitation worker collects litter during the annual Hajj pilgrimage in the holy city of Makkah on August 22, 2018. (AFP/File Photo)

A 2017 study by King Saud University’s Department of Engineering Sciences concluded that Jeddah alone has the potential to produce 180 megawatts (MW) of electricity from garbage incineration and another 87.3 MW from garbage-sourced synthetic gas (syngas).

Another study by Dr. Abdul-Sattar Nizami, assistant professor at the Centre of Excellence in Environmental Studies at Jeddah’s King Abdul Aziz University, estimates that 3 terawatt-hours per year could be generated if all of Saudi Arabia’s food waste was utilized in syngas plants.

Sewage is another valuable resource, in two ways. First, just like household waste, sewage produces methane, which can be harnessed to produce energy. Second, sewage water can be treated and reused for irrigation and industrial purposes.

The potential gasification of solid waste and sewage is especially pertinent to Saudi Arabia, which derives a large proportion of its freshwater from desalinated seawater, every drop of which is precious.

RECYLING IN SAUDI ARABIA

* 15m - Tonnes of garbage produced by KSA per year.

* 50% - Plastic waste collected for recycling.

* 3TW-hours - Energy potential from food waste per year.

The Saudi government has already realized this and is taking proactive steps to generate at least half of its energy requirements from renewables by 2030. “Waste to energy” will no doubt play a role in this new paradigm.

In the city of Marselisborg in Denmark, sewage-derived methane now generates over 150 percent of the electricity needed to run its water-treatment plant. The surplus power is used to pump drinking water to homes and offices.

Much of Saudi Arabia’s sewage is filtered and repurposed, presenting an opportunity to produce cheap and abundant energy.

A similar philosophy can be applied to land use. Areas currently dismissed as wasteland can be reimagined as beautiful public spaces.

A partial view of the Sharaan Nature Reserve near AlUla in northwestern Saudi Arabia. (AFP/File Photo)

King Salman is a pioneer in this regard. Up until his tenure as governor of Riyadh Province, Wadi Hanifah, the dry riverbed that winds down the western edge of Riyadh, was an unsightly dumping ground for garbage and industrial effluent.

Working with an international team of landscapers, botanists and water-management experts, King Salman transformed the wadi into the exquisite meandering parkland it is today, with its thousands of trees, lush wetlands and charming picnic spots.

Another example of wasteland regeneration is the Highline of Manhattan — an elevated rail track that was abandoned after the Port of New York was largely shut down in the 1960s.

Instead of being demolished at great trouble and expense, this rusty eyesore was turned into a lovely green walkway through the concrete jungle and is today a major tourist attraction.

And just as wastelands can be repurposed to create attractive new spaces, many artists are using discarded materials to create stunning sculptures, while making powerful statements about our abuse of the planet.

The Milan-based artist Maria Cristina Finucci used two tons of plastic bottle caps and thousands of red-net food bags, placed inside recycled plastic containers, to spell out the word “HELP.”

One critic described this work as “a cry from humanity ... to curb the environmental disaster of the pollution of the seas.”

A McDonald’s table covered with trash. (Supplied)

In a similar vein, two Singaporean artists, Von Wong and Joshua Goh, created a work called “Plastikophobia” — an immersive art installation made from 18,000 discarded plastic cups, to raise awareness about single-use plastic pollution.

After decades of short-termism and willful denial of environmental destruction, all-encompassing smart waste-management policies are still in their infancy. The know-how and technology exist. They just need to be put into practice.

The Kingdom is already striking out in the right direction. Its Saudi Green Initiative, launched in March, calls for regional cooperation to tackle environmental challenges, boost the use of renewables and eliminate more than 130 million tons of carbon emissions.

The Middle East Green Initiative likewise sets out to reduce carbon emissions by 60 percent across the region.

There are also plans to plant 10 billion trees in the Kingdom and restore 40 million hectares of degraded land, while across the wider region there are plans for 50 billion trees and the restoration of 200 million hectares of degraded land.

Much will depend upon enlightenment and imagination at a societal and individual level. Do we continue to regard our world as a supposedly infinite source of material for our consumption and as a dumping ground for the resulting junk, or do we aim for a cleaner, more sustainable circular economy?

Young people, in particular, are increasingly concerned for the future of their planet and are highly motivated to protect it. This awakening is already beginning to translate into government policy, in Saudi Arabia and around the world.