DUBAI: For Palestinians living in the Gaza Strip, “home” is a concept that rarely conjures images of safety and stability.

Israel and Hamas have fought four short but savage wars since the militant group seized control of this sliver of territory in 2007.

With each wave of violence comes a fresh cycle of destruction and reconstruction, a “recycling of pain,” as Mohamed Abusal, an artist based in Gaza, told Arab News.

At the end of May, tens of thousands of Palestinians returned to their homes in Gaza to inspect the damage following 11 days of fighting — the gravest escalation in hostilities since the 2014 war.

Tens of thousands of Palestinians returned to their homes in Gaza to inspect the damage following 11 days of fighting and bombardment by Israeli forces. (AFP/File Photos)

According to Palestinian officials, at least 2,000 housing units were destroyed and 15,000 damaged by the latest bout of violence, further degrading the already fragile humanitarian situation in Gaza, long squeezed by an Israeli and Egyptian blockade.

Gaza had not yet recovered from the 2014 war when the fighting resumed on May 10. Older buildings now stand like crumbling tombstones alongside newly shattered edifices. It is a sight all too familiar to residents of the territory.

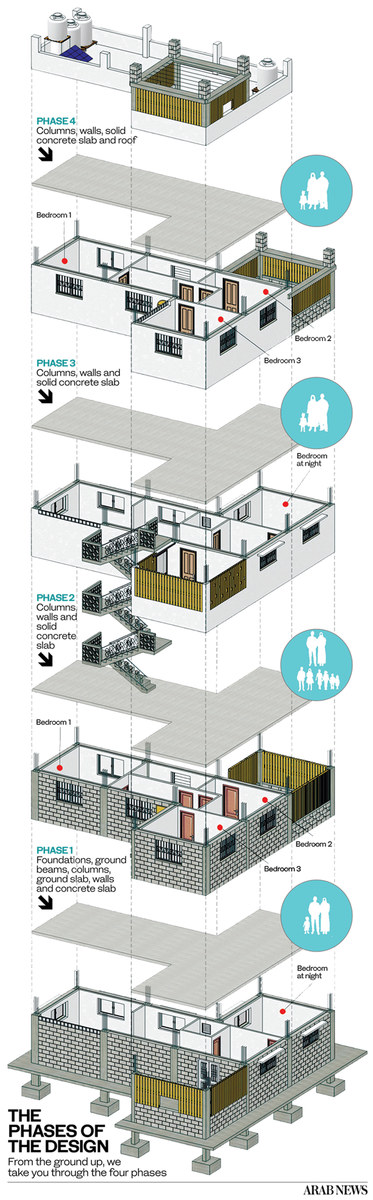

To help redefine Gaza’s ravaged urban topography, Palestinian architect Salem Al-Qudwa has developed a series of designs for self-build homes, which are flexible, green and affordable.

The innovative design means the units can be built on sand or rubble and easily slotted together, allowing extended families to live under one roof — a potential lifeline for those widowed or orphaned by the recent fighting.

“These are homes that can empower the Gazan community,” said Al-Qudwa, a fellow of the Conflict and Peace with Religion and Public Life program at Harvard Divinity School.

Palestinian architect Salem Al-Qudwa

“The Israelis destroyed multi-story buildings and threw their inhabitants into poverty. They have lost everything. This is the problem right now, this endless cycle of destruction and reconstruction, but, more importantly, destroying the physical as well as social fabric of Gazan society.”

Al-Qudwa was appalled to see a repeat of the havoc wreaked on Gaza in 2014.

“Those attacks pushed Gaza back by several decades, destroying the infrastructure of many parts of the city and also the social fabric, which is crucial in relation to housing,” he said. “Now the conflict in 2021 is pushing Gaza back 50 years.”

The 2014 war destroyed around 18,000 homes, leaving an estimated 100,000 Palestinians homeless. However, the temporary wooden structures built by international aid agencies involved in post-war reconstruction were not conducive to the needs of large families and did not provide adequate temperature controls.

Instead of consulting with locals on how to proceed with Gaza’s reconstruction, aid agencies turned to foreign architects, “coming to replace our social structure with a mud house, a sandbag or a wooden shelter,” Al-Qudwa said.

COST OF GAZA WAR

* 77,000 - Gazans internally displaced by May conflict.

* 2,000 - Number of housing units destroyed.

As governments and relief agencies once again pour money into Gaza’s reconstruction effort, Al-Qudwa fears the same flimsy structures will be built, preventing residents from obtaining long-lasting homes that represent stability, permanence and hope for the future.

Al-Qudwa, who was born in 1976 to a Palestinian family in Benghazi, Libya, returned to Gaza at the age of 21 to study architectural engineering at the Islamic University of Gaza. He went on to obtain a Ph.D. from the Oxford School of Architecture at Oxford Brookes University in the UK.

In 2020 he moved to the US with his Palestinian-American family after being awarded a fellowship at Harvard Divinity School.

While working for Islamic Relief Worldwide, Al-Qudwa established the Rehabilitation of Poor and Damaged Houses Project, which designed homes ranging from modest single-room units to spacious houses with shared courtyards, for more than 160 low-income families.

“I helped them build a kitchen, a bathroom and a bedroom and for them it was as if they had a castle,” he said.

House Design Prototype for the Gaza Strip allowing future vertical incremental expansion for families affected by the conflict. (Supplied)

The project was so transformative that it was shortlisted for the World Habitat Award and in 2018 was granted a commendation.

“The project undertaken with Islamic Relief allowed me to work towards characterizing reconstruction projects in terms of their feasibility,” Al-Qudwa said. It also taught him the value of taking into account what communities really want in the form of long-lasting, sustainable housing.

“It led me to ascertain the need for a simple architecture as well as a revaluation of traditional techniques for construction, in line with the participation of inhabitants in the process of designing and building their houses.”

Gaza’s minimalist architecture is a product of its dire circumstances. But Al-Qudwa views his homeland’s rudimentary urban landscape, and even its shortage of building materials, as an opportunity for a more positive social transformation.

Part of the challenge in Gaza stems from the Israeli blockade in place since 2007, which limits access to certain building materials.

Al-Qudwa views his homeland’s rudimentary urban landscape, and even its shortage of building materials, as an opportunity for a more positive social transformation. (Supplied)

Before the occupation, limestone was a common material used in local architecture. It is now far too expensive to import from the West Bank, making concrete from Israel the most popular material of choice.

Al-Qudwa is putting together designs for three five-story homes made of concrete, each with proper insulation and built on strong foundations — in marked contrast with the emergency and transitional structures on offer from aid agencies.

Unlike the monotonous block structures usually wrought from concrete, Al-Qudwa uses the material creatively, enlivening his designs with nods to traditional Arabic motifs, incorporating lattice screens, brick patterns, and even shared courtyards.

Each structure features a row of columns, which allow for additional floors to be added at a later date. “These are ‘columns of hopes’ because with columns you have the idea that something will be added to the structure within a certain period of time,” Al-Qudwa said.

As he has shown through his designs, there are many ways to create low-cost homes that are attractive and also preserve a sense of community, even when resources are scarce.

As Palestinians pick up the pieces from the latest carnage, Al-Qudwa’s work offers a glimmer of hope for a future that is more permanent, both structurally and psychologically. (Supplied)

Moreover, his new prototypes use solar water-heating units, gray-water recycling, and rainwater harvesting systems — all design elements crucial in a region that has long suffered from power cuts and water scarcity.

Al-Qudwa’s sustainable designs run against the grain of other local reconstruction strategies, most notably Rawabi, meaning “The Hills” in Arabic, the first city planned for and by Palestinians in the West Bank near Birzeit and Ramallah.

Stretched across 6.3 square kilometers, the monotonous, block-style structures are arranged in rows, similar to those found in Israeli settlements thrown up in the West Bank.

As Palestinians pick up the pieces from the latest carnage, Al-Qudwa’s work offers a glimmer of hope for a future that is more permanent, both structurally and psychologically.

--------------------

Twitter: @rebeccaaproctor