KARACHI, Pakistan: Spring, 1996. Tulips, poppies and contradictions were blooming across Afghanistan. Uzbeks and Tajiks in the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif were celebrating Nowruz, the Persian New Year. A red flag flew over the city’s Blue Mosque.

Nearby, thousands gathered to watch horsemen play buzkashi, a game similar to polo except the ball is replaced with the carcass of a goat. The sport aptly reflects the violence and power struggles that have marked Afghanistan for centuries.

Almost a thousand miles away, in the southern city of Kandahar, I watched as members of the Taliban, then a newly emerged religious force, held a massive congregation of clerics from the seminaries of Afghanistan and Pakistan.

“The Taliban are counting on the ulema to implement Shariah law on this land of Allah,” Taliban leader Mullah Omar said as a crowd of armed militiamen raised battle cries. “A new generation has to be trained. Our duty is to use force, take weapons … our mission has to be fulfilled.”

My Talib (student) guide explained the significance of Omar’s words. “These madrasah (Islamic college) clerics are our ideological custodians and their students are future soldiers,” he said.

The Taliban initially gained popularity among locals for offering security and an end to the brutal civil war that had been gripping the country.

On crossing the border from Pakistan into the town of Spin Boldak, en route to the Taliban’s headquarters in Kandahar, the group’s distinctive white flags were visible from a distance flying on rooftops and among the surrounding hillocks.

Victorious Taliban fighters mingle with villagers at a town in Kandahar on August 13, 2021. (AFP)

By the time of my next visit to Kandahar, in 1998, the Taliban had seized control of about 90 percent of Afghanistan. Local clerics announced new rules from mosques and over the airwaves of Radio Shariat.

Music, football and kite flying were banned. Men were told to grow beards at least the length of a clenched fist. Women were not allowed to leave their homes unless accompanied by a male relative. The education of girls was prohibited.

I wore a traditional salwar kameez but was still taunted on account of my French beard and uncovered head. My driver had learned to deftly switch music cassettes on the car stereo to play warrior anthems while driving in the city or in the vicinity of Taliban checkpoints.

I had traveled there to cover the first-ever talks between the UN and Mullah Omar at his fortress-like residence.

“The Western world fails to understand the Taliban,” Mullah Muttamaen, a leading member of the group, told me repeatedly. I asked him whether the Taliban, in turn, understood the world. He looked away in tense silence.

While investigating the experiences of minorities under Taliban rule, I found a neighborhood in which Hindus and Sikhs had been ordered to wear yellow cloth to identify themselves. I wrote a story about it that was published while I was still in Afghanistan. After receiving threats, I was forced to flee the country in the dead of night.

Since then, the Taliban has evolved into an organized force. No longer is it an assortment of clueless, brutal men in black turbans riding motorcycles and bullying locals.

When I met Mullah Akhtar Mansour in the late 1990s, he had just been appointed aviation minister by Mullah Omar because he had downed two Russian helicopters with a rocket launcher and was therefore thought to understand how objects worked in the air. He went on to become leader of the Taliban in July 2015, and was killed in a US drone strike in May 2016 after entering Balochistan in Pakistan from Iran.

Taliban fighters stand with their weapons in Ahmad Aba district on the outskirts of Gardez, the capital of Paktia province, on July 18, 2017. (AFP)

Mullah Omar often boasted about how the Taliban movement began with just a few dozen madrasah students with motorcycles and two borrowed vehicles. Now it has developed a hierarchical structure.

Its leaders coalesce in the Leadership Council, or Rehbari Shura, a decision-making body for political and military affairs. It controls many commissions on economics, health and education, operating like a cabinet of ministers.

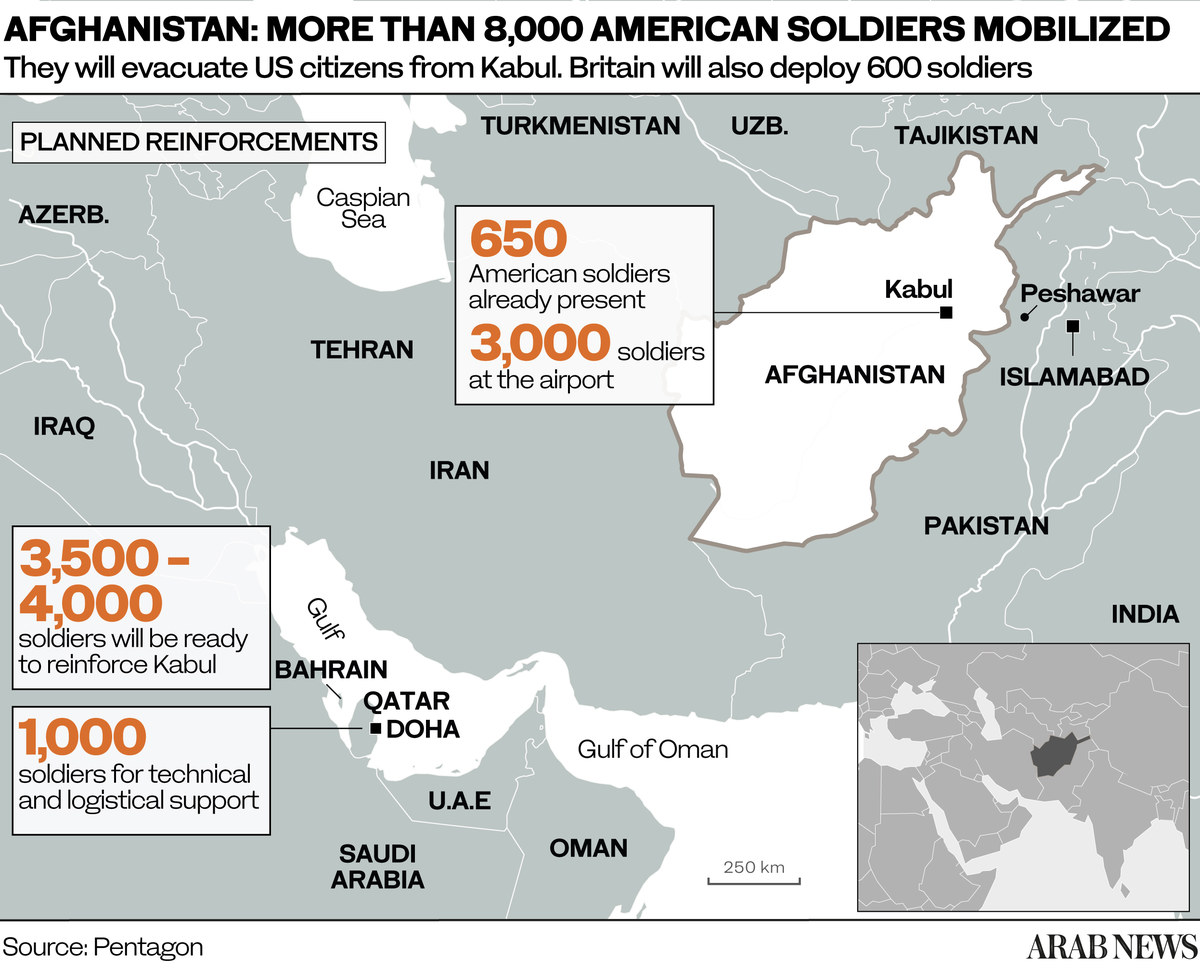

Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar effectively serves as the Taliban’s foreign minister. Its political commission has an office in Doha for international representation, which negotiates with diplomats on the Islamic militia’s behalf. The Taliban has developed ties with Iran, Russia and China in preparation for a potential return to power.

“If our leaders are eating meals with a knife and a fork in Moscow, Beijing, Tehran or Doha, it doesn’t mean we will betray our ideology,” one Taliban leader said.

At one time, young Taliban fighters in Afghanistan feared American air power. I once witnessed a Taliban soldier shouting curses at a formation of B-52 bombers. “Meet us face to face if you have the courage,” he shouted at the sky. Now the group has reportedly used drones in some of its attacks.

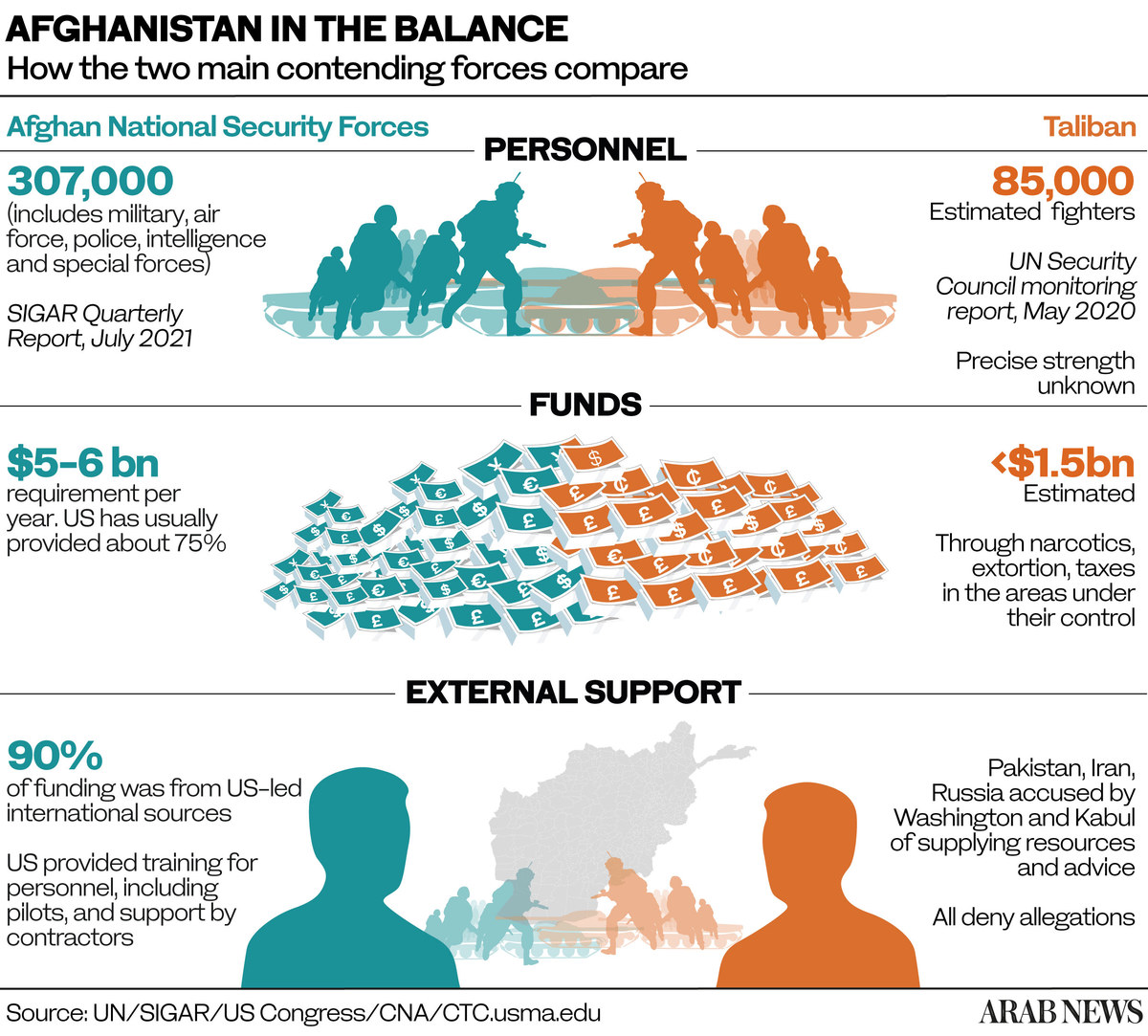

It is estimated that the Taliban currently has between 55,000 and 85,000 trained fighters, and locals say they are better equipped than in previous years.

“They have night-vision goggles, thermal rifle scopes, armored vehicles, bulletproof vests, wireless sets,” said Rashid Khan, a resident of Nimroz province. “They have a huge quantity of American weaponry captured from Afghan forces — even Humvees.”

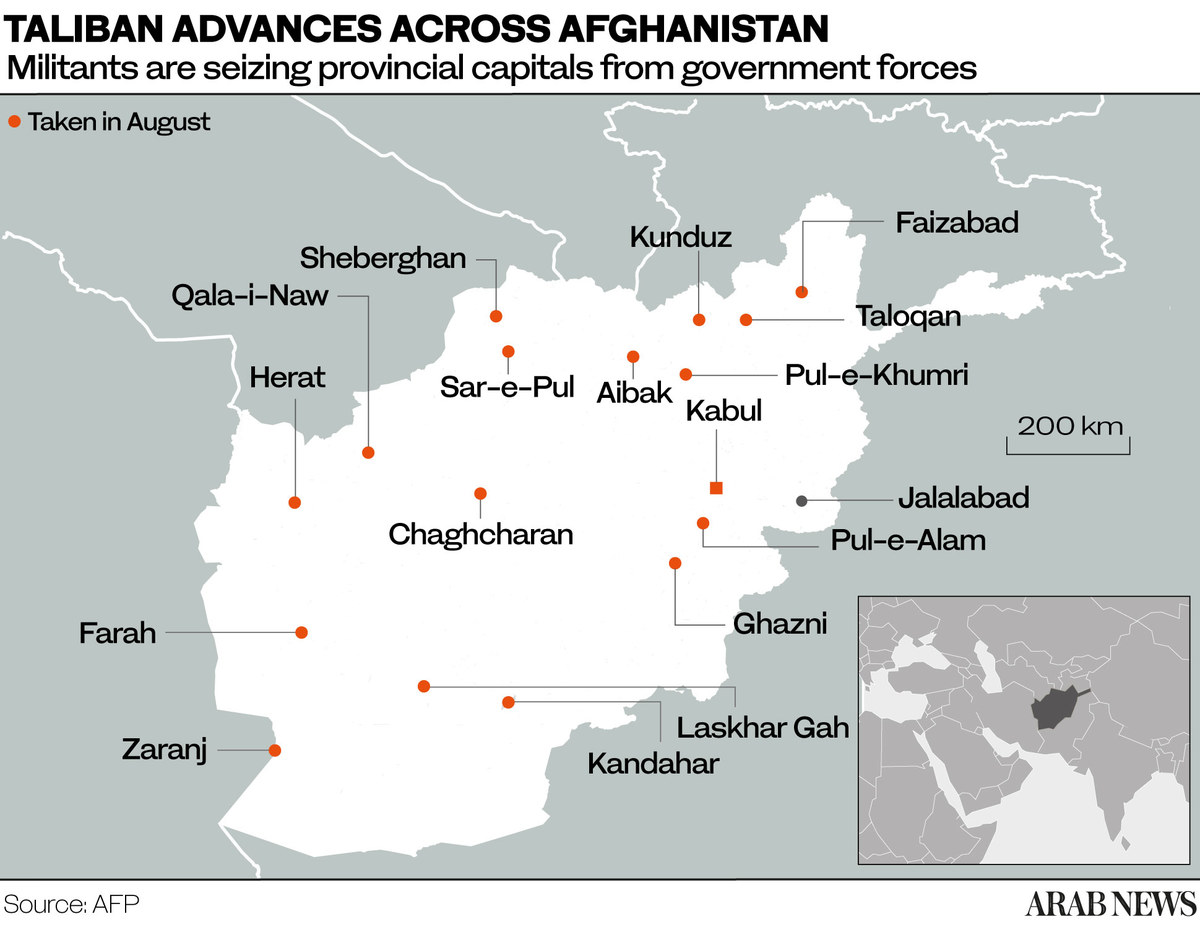

Although Taliban forces appear to be taking control of the country following the recent departure of US troops, with districts and provincial capitals falling like dominoes, reestablishing and maintaining rule across Afghanistan will not be easy.

A man sells Taliban flags in Herat province, west of Kabul, Afghanistan, on Aug. 14, 2021. (AP Photo/Hamed Sarfarazi)

They will face opposition from a new generation of Afghans, including educated youths who bitterly oppose the group’s return to power.

During recent peace talks there has been much speculation about just how much the Taliban has changed in the past two decades in terms of governance, adherence to human rights, artistic expression, and whether women will be allowed to work and girls to go to school.

The group’s political leaders know that the methods of the past will not grant them legitimacy, but the fighters on the ground are ideologically committed to establishing an “Islamic emirate.”

The latter include the men who shot dead the comedian Nazar Mohammad Khasha in Kandahar in July. In another incident, two alleged kidnappers were publicly executed without a trial. Reports are also circulating about various restrictions already being placed on women.

It seems the Taliban now has three faces: The Rahbari Shura leaders who are the custodians of the Taliban ideology; the political Shura leaders who are trying to gain legitimacy by improving the Taliban’s public image; and the mass of fighters forged in war.

Taliban negotiators walk down a hotel lobby during the talks in Qatar's capital Doha on August 12, 2021. (KARIM JAAFAR / AFP)

There is also uncertainty over whether the Taliban can or will prevent Afghanistan from once again becoming a global hub for terrorism. More than 2,000 militants affiliated with Daesh are reportedly operating in the country.

There is additionally the issue of the Pakistani Taliban using Afghanistan as a safe haven from which to launch attacks in Pakistan.

It will be difficult for the Afghan Taliban to sever ties with Al-Qaeda and the Pakistani Taliban, even if it wants to, because the trio formed a nexus during the course of the “war on terror.”

While many analysts were surprised by how quickly the Taliban regime fell after the 2001 US invasion, porous borders continued to provide a sanctuary for its members. Many crossed into Pakistan’s Balochistan province with their families.

Much of the border has since been fenced but at the time, Taliban fighters in remote villages in Zabul and Uruzgan provinces were betting on the US forces eventually getting tired of fighting.

“Mullah Omar has said: ‘Americans have the clocks but we have the time,’” as one seasoned fighter put it. The Taliban’s perception of having time on its side persists.

For more than 40 years Afghanistan has been a battlefield of conflicting ideologies and ethnicities — a bloody tug-of-war between warlords over opium and opportunities for corruption.

I am reminded of the words of Shahrbano, a young Afghan woman I met in Peshawar years ago whose family twice had to flee Kabul: once due to Mujahideen infighting, which reduced the city to ruins, and again during the regressive rule of the Taliban.

“With every invasion, be it Russians or Americans or Mujahids or Taliban, each Afghan dies a little,” she said. “We are the target in this game of death, like a carcass in buzkashi — and the world watches it, again and again.”