DUBAI: Four Saudi universities have claimed the top five positions in a new ranking of Arab academic institutions, a sign that investment in higher education is paying off.

King Abdulaziz University took first place in the table produced by Times Higher Education, followed by Thuwal’s King Abdullah University of Science and Technology and Alkhobar’s Prince Mohammad bin Fahd University in third and fourth respectively. Dammam’s King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals took fifth place, followed by Riyadh’s King Saud University in eighth.

Saudi Arabia’s achievements are, however, not quite reflective of the Arab world as a whole, according to experts who say the Middle East still has a long way to go to build a strong and sustainable higher-education system.

“Saudi Arabia has been building up research capacity across multiple institutions, and recruiting some of the best and brightest academics from across the world,” Natasha Ridge, executive director at the Sheikh Saud bin Saqr Al-Qasimi Foundation for Policy Research in Ras Al-Khaimah in the UAE, told Arab News.

“This investment over time is really starting to pay off. This is coupled with the opening up of the Kingdom to tourism, which more generally has meant that it’s no longer an isolated enclave but a vibrant and connected country that can now attract both students and faculty from across the world,” she said.

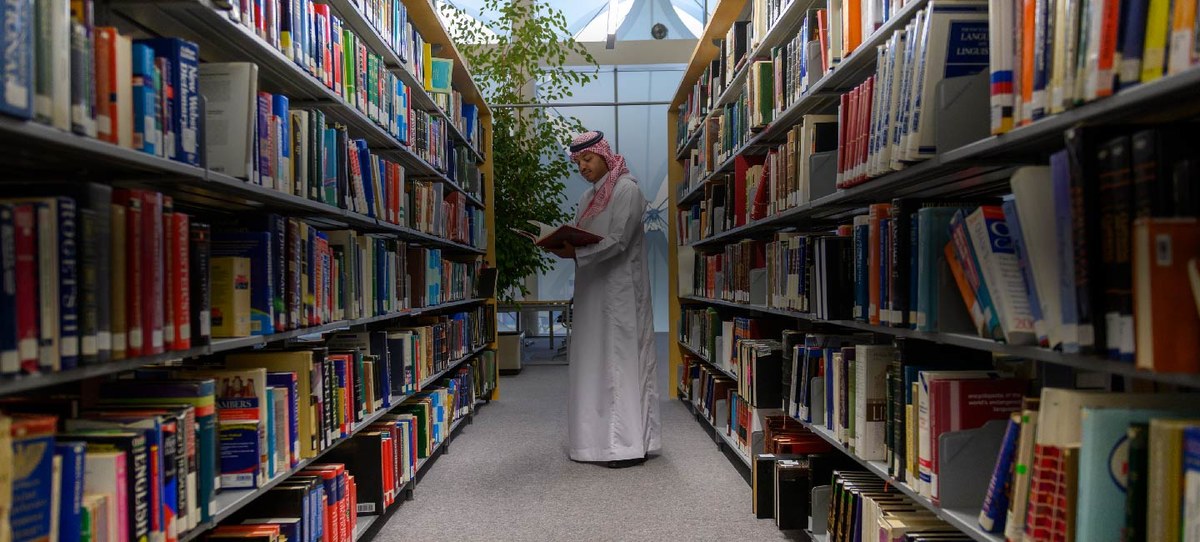

Judith Finnemore, an education consultant in the UAE, believes that Saudi Arabia’s higher-education success story is rooted in its recent drive to attract international expertise and develop quality research infrastructure. (AFP/File Photo)

“You can see that Saudi Arabia has the majority of universities in the top 10 of every category, indicating a holistic approach to higher education.”

Judith Finnemore, an education consultant in the UAE, believes that Saudi Arabia’s higher-education success story is rooted in its recent drive to attract international expertise and develop quality research infrastructure, which were once the exclusive preserve of institutions in the West.

“It has done this because it realizes that shoveling its school leavers off to foreign universities isn’t conducive to alleviating the brain drain,” Finnemore told Arab News.

“They were seeing a ‘finished product’ but not realizing the advantages of having innovation and research available in-country.”

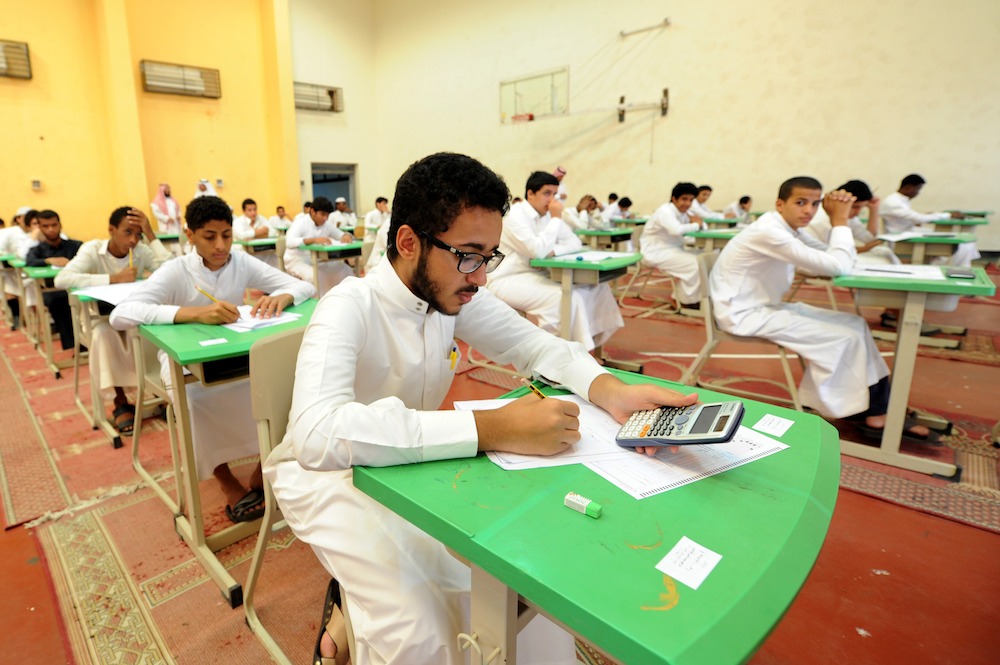

Saudi Arabia, along with other GCC countries, could well become the trailblazers in achieving the ambitious goal of combining higher education and sustainable development. (AFP/File Photo)

Ridge said there are currently far too many students studying just a handful of subjects such as business administration, and not enough opting for courses in psychology and education — sectors in urgent need of more graduates.

This is partly the result of low funding for research in social sciences, especially relating to the public sector, such as education, urban planning and public health, among others.

“We still need a lot more locally conducted research on issues particular to the region so that policymakers can be more effective,” Ridge said.

Also, once students graduate they often leave university without the skills sought by employers.

“There’s a lack of vocational education and colleges to train people in trades and other more applied fields,” Ridge said.

Although university staff are often paid well, long teaching hours can take away from other important aspects of their work.

ARAB UNIVERSITYRANKINGS 2021

1 King Abdulaziz University (KSA)

2 Qatar University (Qatar)

3 King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KSA)

4 Prince Mohammad bin Fahd University (KSA)

5 King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KSA)

6 Khalifa University (UAE)

7 United Arab Emirates University (UAE)

8 King Saud University (KSA)

9 American University of Beirut (Lebanon)

10 Zewail City of Science and Technology (Egypt)

“While some countries and universities can pay high salaries to attract high-performing faculty, many can’t, and on top of that they require faculty to have very high teaching loads, which then limits the amount of research they can do,” Ridge said.

“This then impacts the rankings of the universities if faculty aren’t publishing enough papers.”

While there have been enormous strides in the adoption of technology in further education, Finnemore said access to digital learning and research aids is by no means guaranteed across the region.

“In all societies, the need for on-the-go education provided by distance learning and apps is taking off globally,” she added.

“This will enable learning to be real and much more useful to the workforce than turning out batches of graduates who then go out to seek work.”

With their large youth populations and the advantage of oil wealth, GCC countries could avoid the “baggage” of traditional educational approaches and create a school-to-workforce pipeline that propels industries ahead of the rest of the world. (Supplied)

Although the quality and availability of higher education will no doubt continue to improve, especially in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member states, these nations can only stand to benefit if enough graduate jobs are created and if students themselves pursue degrees in a wider variety of disciplines.

“In the longer-established systems such as Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon, there have been ongoing concerns about the employability of graduates and the number of people pursuing a university education and then being unemployed,” Ridge said.

“Without a strong and culturally valued vocational sector, low-quality institutions will keep producing graduates who then can’t find work and feel disillusioned about their future, leading to social unrest.”

There are signs, though, that students are adapting. The COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, has forced young people to embrace different learning formats.

“But there isn’t necessarily a wholesale take-up from more traditional faculty reluctant to relinquish the lecturing role,” Finnemore said.

“If more fluid structures do evolve, I can see this as a way to ensure a greatly more educated workforce, because the less rigid approach could appeal to a far wider spread of the population, like women and rural dwellers, among others.”

Such work is crucial as the GCC states transition to a more knowledge-based economy. With their large youth populations and the advantage of oil wealth, these countries could avoid the “baggage” of traditional educational approaches and create a school-to-workforce pipeline that propels industries ahead of the rest of the world. “This is what happened in places like Singapore, and look where they are,” Finnemore said.

Ridge said: “Without high-performing higher-education institutions, countries in the Middle East will have to keep depending on expertise from elsewhere, whether paid for by aid programs or by their own governments. This isn’t sustainable or efficient for the future of the region.”

Four universities in Saudi Arabia have claimed the top five positions in a new ranking of academic institutions across the Arab world. (AFP/File Photo)

Put another way, the entire sustainable development agenda in the Middle East must be built on the solid foundations of a top-notch higher-education sector.

Saudi Arabia, along with other GCC countries, could well become the trailblazers in achieving this ambitious goal.

Take Riyadh’s Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, the largest women’s university in the world. Recently, it became the first university in Saudi Arabia to win accreditation to award its staff the Advance HE Fellowship upon completion of its Academic Excellence Program.

Led by staff at its Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, under the umbrella of the Academic Development Deanship, PNU has been working toward accreditation for the past three years, establishing a strong team of fellows as part of a growing fellowship community of almost 150,000.

“We’re delighted to have achieved accreditation for the AEP, a professional development and recognition scheme,” Ola Elshurafa, an academic consultant and AEP scheme leader at the CETL, and herself a senior fellow, told Arab News.

“This achievement is a significant milestone in our work toward teaching excellence across PNU by recognizing and rewarding the commitment of individuals in their continuous professional development,” she said.

“We’re committed to supporting PNU faculty and staff in their journey toward quality education, in light of international standards, for the improvement of student learning and achievement.”

------------------

Twitter: @CalineMalek