STOCKHOLM: Since the trial of Hamid Noury, 60, began on Aug. 10, Swedish Iranians have gathered daily outside a court building to draw the world’s attention to the former Iranian prison official’s alleged crimes. The Stockholm District Court’s century-old thick stone walls have palpably failed to keep out the sounds of protest.

During a court appearance last week, Noury complained that the protesters’ chants and slogans were “insulting,” forcing the judge to ask police to request the crowd outside to quieten down.

The trial is connected to the mass execution in July and August 1988 of political prisoners who were members or sympathizers of the armed leftwing group Mujahedin-e Khalq (MEK), also known as the People’s Mujahedin Organization of Iran.

As an alleged assistant to one of the special-tribunal prosecutors, Noury is said to have been a key actor in the executions at Gohardasht prison, a facility on the northern outskirts of Karaj, about 20 km west of the capital Tehran.

The prosecution says that Noury facilitated death sentences, sent prisoners to execution and helped prosecutors gather prisoners’ names. He has denied all of the charges while claiming that the sentences were justified because of a fatwa, or religious ruling, by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Iran’s supreme leader at the time.

The fatwa, issued in 1988, targeted the MEK, which had been outlawed by the Islamic regime in 1981 and held responsible for a series of anti-regime attacks at the end of the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq War. The MEK had been operating since 1986 from Iraq, then ruled by Iran’s archfoe Saddam Hussein.

Massoud Radjavi and his wife Maryam (R), leaders of the Iranian opposition movement the People's Mujahedeen (MEK), review militants celebrating their wedding 19 June 1985 at the headquarters of the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI). (AFP/File Photo)

The families of the victims of the executions have waited three decades for justice. Now, after a complex Swedish police investigation into the suspected murders of political prisoners, they could soon find a measure of closure.

Survivors of the anti-MEK purge have testified that several inmates already had the hangman’s noose around their necks when Noury led them down what was known among prisoners as a “death corridor,” to await their hearing.

Noury is alleged to have read out the names of those who would face the specially appointed tribunal, which had likewise been nicknamed “the death commission.” Few renounced their allegiance to the MEK, so few ended up avoiding the death penalty.

“It was a kangaroo court where the so-called trial took one to two minutes,” Shahin Gobadi, a spokesman for the MEK-affiliated National Council of Resistance of Iran, told Arab News while participating in a protest last week outside the Stockholm District Court by exiled Iranians, former political prisoners and families of victims of the secret executions.

Gobadi added: “Noury served pastries to the judges on the ‘death commission’ and to the prison guards to celebrate a ‘good day’s work’.”

In one witness statement, Noury was described as “particularly cold-blooded” compared with other officials involved in a veritable industrial production-line killing system.

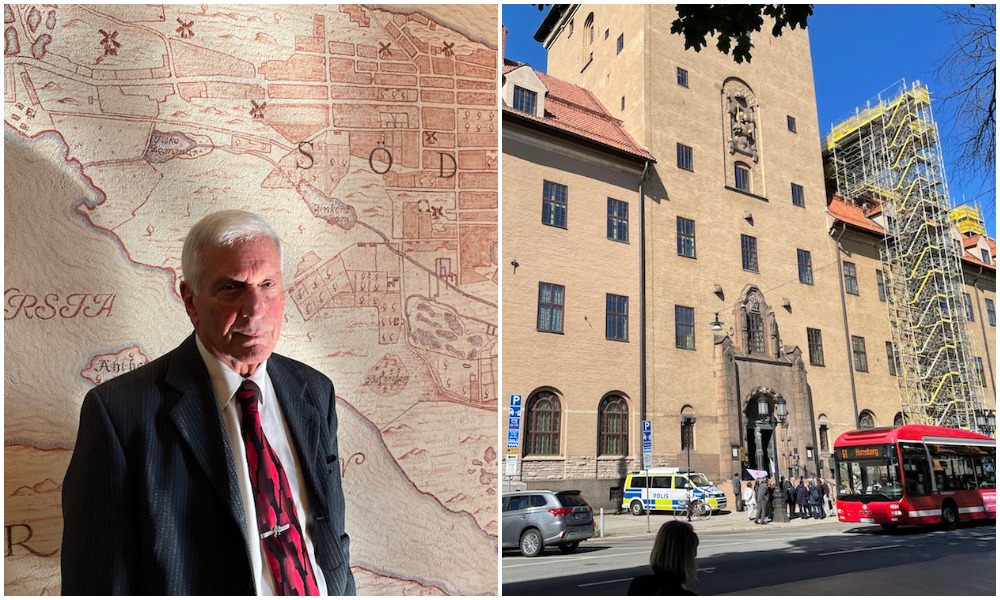

Kenneth Lewis (L) represents several of the plaintiffs, with the trial taking place at Stockholm District Court. (Photos by Ann Tornkvist)

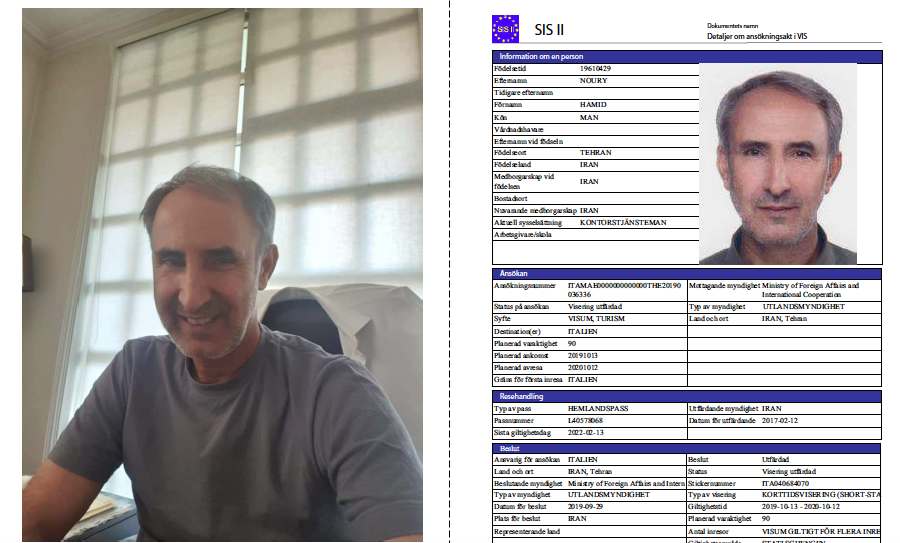

Activists managed to lure Noury to Scandinavia with a bogus offer of a luxury cruise, before tipping off local police about his scheduled arrival. Since his arrest at Stockholm airport in November 2019, the case against him has expanded.

Kenneth Lewis, representing several of the plaintiffs, told the court that although 500 to 600 prisoners were known to have died at Gohardasht within the space of a few weeks, this was merely one of several prisons where executions were taking place.

A 2018 report by human rights monitor Amnesty International, “Blood-Soaked Secrets: Why Iran’s 1988 prison massacres are ongoing crimes against humanity,” places the death toll in regime jails at about 5,000.

In the wider crackdown, which was not reserved to the prisons, an estimated 30,000 Iranian dissidents are thought to have been killed. Lewis pointed out that this toll far exceeds other well-known atrocities, including Srebrenica in Bosnia.

“It is my belief, however, that the motive, not the numbers, define genocide,” Lewis told the court in his opening statement. Indeed, Khomeini’s son and right-hand man Ahmad Khomeini is alleged to have argued strongly in favor of the fatwa at issue, saying it was time to “exterminate” the MEK in retaliation for its anti-regime activities.

“It is our view that these executions constitute genocide because the fatwa was issued with the purpose of exterminating the (MEK) based on the (regime’s) religious opinion,” Lewis said.

Image of Hamid Noury and his profile from the case with Swedish police. (Photo by Ann Tornkvist)

Ali Doustkam, who fled to Sweden in 1994 and has attended the protests in Stockholm, says that the trauma of the 1988 fatwa persists despite the passage of time. “The prisoners who were executed were discarded in mass graves. Their families have not been able to bury them to this day,” Doustkam told Arab News.

According to him, suspected MEK members eliminated by the regime outside the prison system were also treated with the same disrespect in death. Branded enemies of God, they were denied the right to burial in communal cemeteries among the devout. “Parents were forced to bury their children in their backyard,” Doustkam said.

In Gobadi’s view, the Iranian “government of mass murderers” has not only avoided accountability for its actions, but has rewarded its functionaries for their “ruthless savagery,” among them Iran’s new president and former judiciary chief Ebrahim Raisi, who Amnesty accuses of being a member of the “death commission” behind the secret executions.

Raisi has denied involvement, but praised Khomeini’s “order” to carry out the purge.

“It is our ultimate wish that a conviction here leads to Noury and members of the Iranian regime being tried for crimes against humanity at an international tribunal,” Doustkam said.

Noury’s defense team has contested the evidence against their client, highlighting perceived inconsistencies and unverifiable information in witness testimonies. They have also implied that groups on social media have created echo chambers where inaccuracies have percolated over many years, converting mere hearsay into supposed facts.

The trial is connected to the mass execution in July and August 1988 of political prisoners who were members or sympathizers of the armed leftwing group Mujahedin-e Khalq (MEK). (Photo by Ann Tornkvist)

The defense has also pointed out that none of the witnesses have identified Noury as a member of the actual “death commission” tribunal, meaning he had no formal decision-making or sentencing powers. They deny Noury even worked at the prison.

While such arguments carry weight in a court of law, the families of Noury’s alleged victims are in no doubt about his moral guilt.

“He might have been a low-level operator,” Gobadi said. “But he was an integral part of the ruthless regime in Iran.”

Although only one individual is standing trial, the families of the victims of the secret executions understand the symbolic value of a successful prosecution and the possible knock-on effects.

“What is unusual about this trial is that it’s most importantly an indictment of the entire Iranian regime, and that’s a huge problem for them,” Lewis, the plaintiffs’ lawyer, told Arab News.

While Kristina Lindhoff Carleson, the lead prosecutor in the case, has ruled that there is sufficient evidence to charge Noury with only 100 killings, the sight of even one suspect being led into a courtroom in handcuffs is unprecedented.

During a court appearance last week, Noury complained that the protesters’ chants and slogans were “insulting,” forcing the judge to ask police to request the crowd outside to quieten down. (Photo by Ann Tornkvist)

“This milestone trial in Sweden comes after decades of persistence by Iranian families and victims of the 1988 mass executions,” Balkees Jarrah, associate international justice director at Human Rights Watch (HRW), said in a statement. “This case moves victims closer to justice for the crimes committed more than 30 years ago.”

The trial is only possible in Sweden because the Nordic country recognizes universal jurisdiction over certain serious crimes such as mass murder, allowing for investigation and prosecution regardless of where the crimes were committed.

HRW has said that universal jurisdiction cases are important for ensuring that those who committed atrocities are held accountable. It says the process provides justice to victims who have nowhere else to turn, and that it deters future crimes by ensuring that countries do not become safe havens for rights abusers.

“Universal jurisdiction laws are a key tool against impunity for heinous crimes, especially when no other viable justice option exists,” Jarrah said.

Members of the Swedish-Iranian community have told local media how proud they are to see authorities in their adopted home bring one of their tormentors to justice.

A verdict is expected in April 2022.