NEW YORK CITY: Suzanne Plunkett, a New York-based photojournalist, had set an early alarm to cover a Fashion Week shoot in Lower Manhattan, a highlight in the city’s social and commercial calendar, for the Associated Press.

A few hours earlier, Mohammed Atta and 18 other men had boarded four commercial flights bound for California, none of which would reach their destinations.

Before heading out, Plunkett turned on the television for the latest weather report. Although it was a clear autumn morning on Tuesday, Sept. 11, the weather on the East Coast can be temperamental and liable to change abruptly.

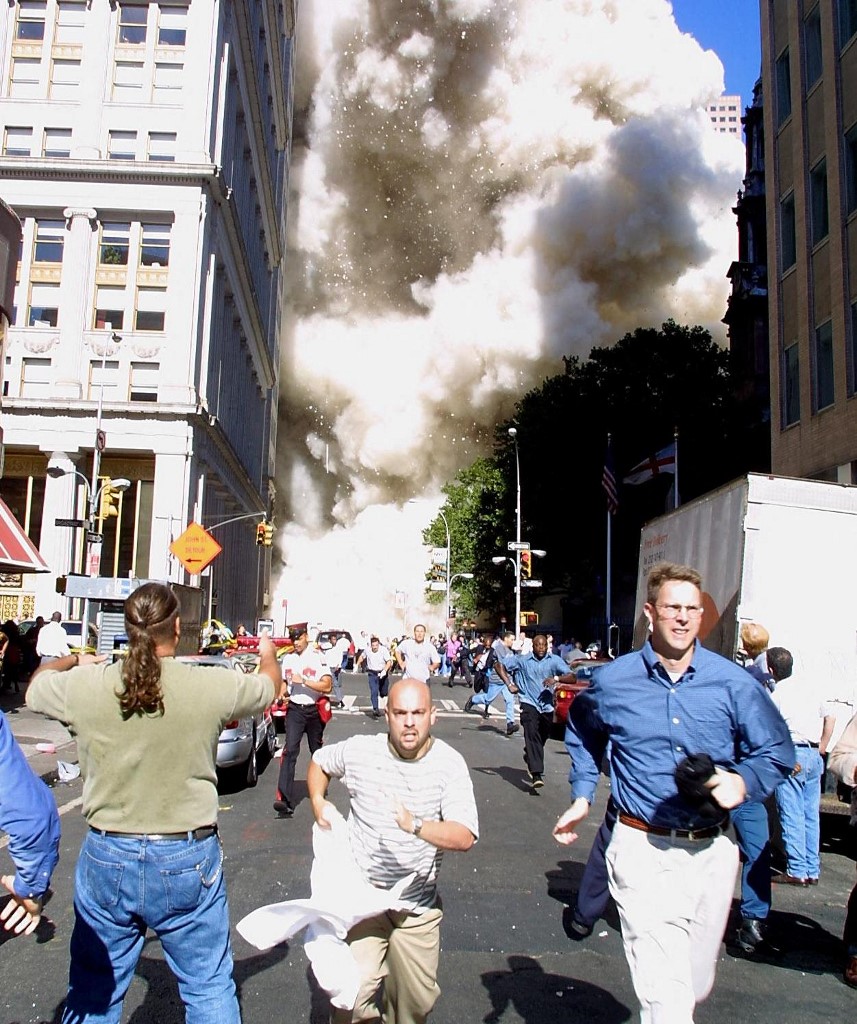

In this file photo a tower of the World Trade Center collapses in lower Manhattan, New York on September 11, 2001. (File/AFP)

What she saw were rolling images of a great smoldering gash in the side of the North Tower of the World Trade Center, where American Airlines Flight 11 had struck the steel and glass giant just minutes earlier.

Watching as burning jet fuel engulfed everything between the 93rd and 99th floors, Plunkett wondered how the fire department would respond to what many then believed was nothing more than a tragic accident.

Then her pager buzzed. Grabbing her camera bag, Plunkett dashed out of her East Village apartment and hopped on the subway. Minutes later, United Airlines Flight 175 smashed into the South Tower. This was no freak accident.

In this file photo smoke continues to rise from the destroyed World Trade Center in lower Manhattan, New York on September 15, 2001. (File/AFP)

Plunkett emerged from the subway at the intersection of Fulton Street and Broadway to find scenes of utter chaos, as emergency vehicles and frightened commuters tore past, all eyes turned upward.

Meanwhile, inside the burning towers, workers were scrambling for the stairwell exits. More than 50,000 people worked in the 25-year-old complex, at one time the world’s tallest.

Those trapped above the burning floors were left with little choice but to wait and pray for rescue. In the end, however, more than 200 jumped to their deaths rather than succumb to the heat and smoke.

In this file photo smoke continues to rise from the destroyed World Trade Center in lower Manhattan, New York on September 15, 2001. (File/AFP)

On the ground below, first responders worked frantically to evacuate the complex. As the panicked crowd rushed toward her, Plunkett pressed her face to the viewfinder and snapped away. Everywhere she looked were ghostly faces contorted with terror.

“Then someone yelled: ‘The tower is coming down,’” she told Arab News, recalling the day’s events 20 years later.

Just an hour after the second plane hit, the 110-story South Tower came crashing down, killing 614 workers still trapped inside.

As an immense cloud of dust and debris swept through the surrounding streets, people ran for cover. In one of Plunkett’s photos, a man wearing a shirt and tie runs into the frame, his face a picture of terror.

“When the gentleman with a tie went by, I remember thinking, ‘that’s enough,’” Plunkett said. “I turned and started running.”

Taking cover inside a tiny beeper store with 15 other people, she sat down at the cash register, hooked up her laptop and clunky old Nokia and began transmitting her images to the AP bureau.

Minutes later, her now-iconic photograph of petrified pedestrians, among them the man in the shirt and tie, was circulating around the globe.

An hour and 40 minutes after the first plane hit, the North Tower fell, killing 1,402 workers trapped inside.

Twenty years on, Plunkett admits it is still hard to talk about the day’s traumatic events. “It hasn’t gone away. Residuals are here. I have done therapy, but I still feel shaky when I talk about it,” she said.

A hijacked commercial plane crashes into the World Trade Center 11 September 2001 in New York. (FIle/AFP)

From her apartment in London, where she now lives, Plunkett unearths the old images and clicks her way through, allowing the visuals to guide her story — pictures of the numbed and dazed wandering aimlessly, covered in dirt, some weeping, others strangely calm and confused.

New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani had by then ordered the evacuation of Lower Manhattan. Wrapping her cardigan around her head to keep choking yellow dust from her eyes and lungs, Plunkett joined the exodus heading north towards City Hall. Later she headed to Chelsea Piers where a triage center had been established.

“It was a huge place, completely empty,” Plunkett recalled. “There were a lot of doctors but there was nobody there for treatment. There were ambulances but they had nobody to help. Everyone had died.”

Airline Pilots stand in prayer during a wreath laying ceremony for the 9/11 Pentagon victims on Patriot's Day. (File/AFP)

At 3 o’clock in the morning, she walked back to her East Village apartment. That morning’s preparations for the Fashion Week photoshoot no doubt felt like a lifetime ago.

“After taking a shower and getting into bed, I remember feeling my skin prickling as if there was glass under it. It was all the dust, the pain and the exhaustion.”

Despite Guiliani’s appeals to New Yorkers to stay and help get their city moving again, Plunkett knew right then and there that nothing about the life she had built for herself in the East Village would ever be the same again.

Al Kim visits the National 9/11 Memorial & Museum on July 12, 2021 in New York City, honoring those who were killed in the 2001 and 1993 attacks. (File/AFP)

“I was perfectly happy being in New York, not knowing much about the world and international politics. My dream in life was to work in the city and for a wire service. I had achieved my dream. I was in my early 30s and that was it: I thought New York was the pinnacle of everything,” she said.

“Suddenly, 9/11 woke me up. It made me question where I was from, and why the world didn’t like Americans.” The attacks also shattered every notion Americans had about war. It was no longer “over there.” It was happening on their soil.

“There was this American sentiment of ‘let’s get them, we were wronged and we’re gonna get them.’ And I’ve never been gung-ho about the retribution thing. My overriding feeling was that I had to get out of New York.”

Early reports of 10,000 casualties in New York, in Virginia where American Airlines Flight 77 had struck the Pentagon, and in Pennsylvania where United Airlines Flight 93 had crashed into a field, were later revised down to 2,996, including the 19 hijackers.

An aerial view shows the ground zero and 9/11 memorial pools amid the city skyline of lower Manhattan and New York city. (File/AFP)

As recovery crews descended on “ground zero,” news channels carried live coverage of the search for survivors among the roughly 1.8 million tons of debris.

“I remember just being tired of having to cover anything that had to do with 9/11,” Plunkett said. “With every assignment I had, I was like ‘no, we’re just rubbing our noses in it.’

“In a lot of war situations, you’ve got your family to look after you. And I remember in the days following 9/11, everybody in New York was messed up. People were just openly crying while walking down the street and there was no relief.”

Kristina Hollywood and her daughter Allyson attend a candlelight vigil for 9/11 victims at a memorial site following the death of Osama bin Laden May 2, 2011. (File/AFP)

Leaving New York behind, Plunkett joined legions of journalists heading to the new front in the “war on terror” — Afghanistan. It was here that Al-Qaeda chief Osama bin Laden, the architect of 9/11, was thought to be hiding out. It would be another 10 years before the US caught up with him in neighboring Pakistan.

“It feels cracked to talk about 9/11 and not to talk about Afghanistan,” Plunkett said. “It was such a hopeful time (in Kabul). It felt like things couldn’t go back. We felt like the Taliban were done. Women could go out. Women were learning to drive.

“I did all kinds of the visual tropes that all photographers went and did. We went into a beauty salon and suddenly the women were grabbing me, doing my make-up, hair, and we had this connection, this lovely feeling that it’s over. There was a kind of relief.”

Now Plunkett describes her heartbreak at seeing the gains of the last 20 years come undone with the return of the Taliban. “I am really upset now about what’s happening in Afghanistan. I am not the one to ask about the politics of it, but I do feel that Afghanistan has been abandoned.”

Patrick Delaney holds a picture of his former friend, firefighter Robert Wallace, outside of Ground Zero on the eighth anniversary of the Sept. 11, 2001 extremist attacks. (File/AFP)

Plunkett has returned to New York only once since the events of 9/11. In 2018 she went back to her grungy East Village apartment block to find it had been gentrified, the authentic grittiness she fondly recalled since heavily diluted.

Like her old neighborhood, she too had changed. Witnessing and capturing the events of 9/11, covering America’s long Afghan mission, and meeting the Afghan people had challenged her preconceptions about humanity and the world beyond her sheltered Midwest upbringing.

“The whole experience made me more accepting. I didn’t have a lot of tolerance for anybody different. I grew up in a tiny suburb in Minneapolis. That was all I knew,” she said.

“The world is a complicated place. It is so important to be informed and not be in a bubble. There is so much going on that we don’t see. On Sept. 10, I wish I’d known. It’s important not to have blinkers on.

“9/11 catapulted me into that, and it shouldn’t have to take an event of such magnitude for us to seek out people who are not like us, and learn about what makes them tick. Essentially, they’re just like us.”

Twitter: @EphremKossaify