DUBAI: The Al-Qaeda conspirators who selected the Twin Towers of New York’s World Trade Center for the main focus of their 9/11 attack knew what they were doing. The towers represented American power and bravura, but also symbolized the global dominance of the US financial system.

The banks, investment firms and stock brokers in the Twin Towers ran the global capitalist system; bring them down and it would be a body blow to US financial hegemony, paving the way for an “Islamic caliphate.”

Traders begin their work on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange after observing two minutes of silence before the start of the trading day 17 September, 2001. (File/AFP)

The effect when the towers fell was immediately apparent in downtown Manhattan, where they had stood since 1973. Three years after the attacks, Mike Bloomberg, then mayor of New York, told an investigating commission: “The 9/11 attacks took an enormous toll on New York City and New York state. They contributed to a decline in tax revenues totaling almost $3 billion in 2002.”

Inside the towers, the human carnage was terrible. In one investment firm, Cantor Fitzgerald, which occupied floors 101 to 105 of the North Tower, every employee who reported to work that day died in the attack. Other blue-blooded Wall Street banks, notably Morgan Stanley, also suffered terribly.

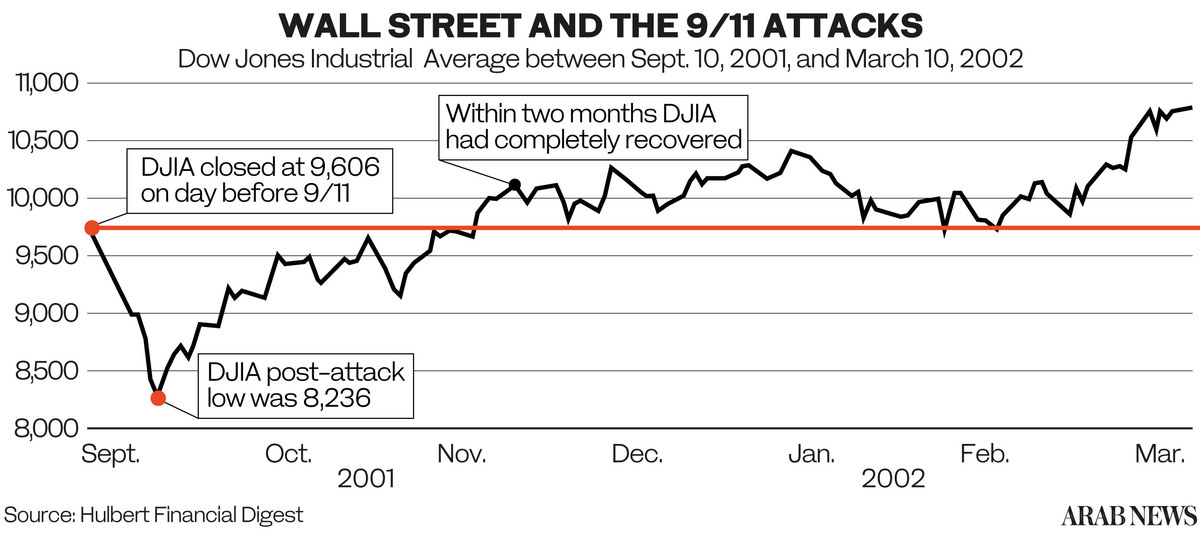

In such circumstances, the immediate economic and financial fallout was grim. The US financial system did indeed grind to a halt, as the attackers had intended. American financial markets, including the New York Stock Exchange just a few blocks away from “ground zero,” closed immediately.

A hijacked commercial plane crashes into the World Trade Center 11 September 2001 in New York. (File/AFP)

Huge chunks of American and global economic life simply stopped working. The aviation industry was grounded in the US for days, and elsewhere was subject to the tightest restrictions imaginable to prevent further attacks. Global trade and commerce dipped as a result. The insurance and financial industries were especially badly hit.

Oil markets, which had been healthy for the period before the attacks, nearly halved in the week after, amid growing fears for oil demand at a time of huge economic uncertainty. It would take until spring 2002, and worries for oil supply from the Middle East as America’s military response to the attacks became apparent, for oil to regain pre-9/11 levels.

When financial markets did reopen after a week of forced closure, they suffered a 10 percent crash in early trading, and took nearly two months to get back to pre-9/11 levels. In the circumstances of the worst terrorist attack in history, the fact that markets recovered in such a short space of time can probably be viewed as testimony to the system’s resilience.

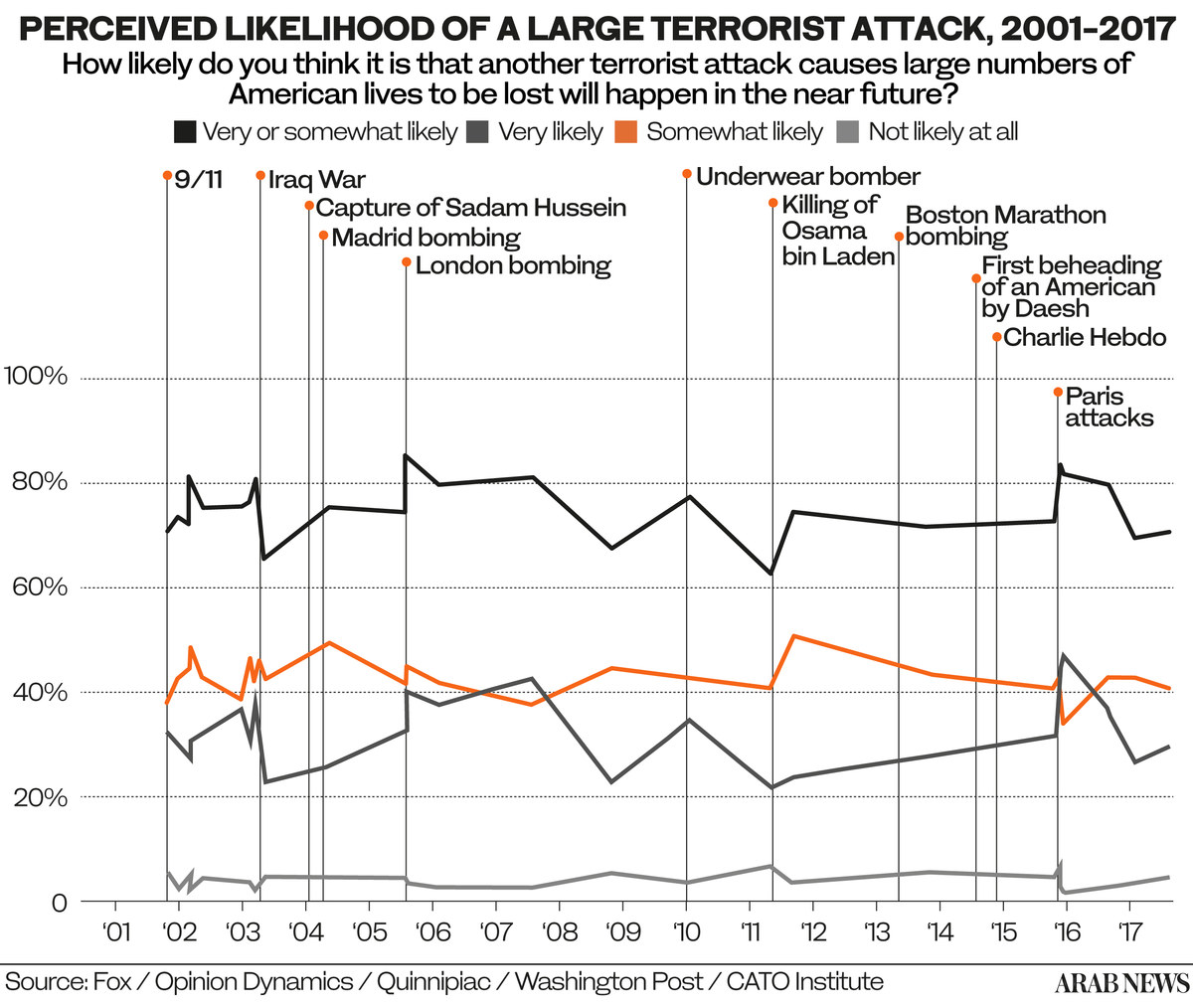

But the longer-term repercussions were to be more serious. Nearly eight years after 9/11, the Department of Homeland Security conducted an in-depth analysis of the economic effect of the attacks, and concluded: “In addition to the direct impacts of fatalities and injuries, destroyed property, and business interruption in New York City, there was the emergence of the ‘fear factor’ and the range of fiscal and monetary policy responses undertaken by the US government that sustained economic activity.”

The “fear factor” had direct repercussions for Saudi Arabia and for the economies of the Middle East. “The uneasy but mutually beneficial political and economic relationship between the US and the Gulf Arab states was shaken to its core” by the attacks, said a prominent Middle East banker who requested anonymity because of the sensitivity of the events even two decades later. Furthermore, as he pointed out, there was a “discernible rise in anti-Arab sentiment in the US.”

There was certainly a witch-hunt in the US to identify the backers of the Al-Qaeda terrorists, which had the effect of casting blame far and wide, including Saudi and other Gulf financial institutions that were deemed to be responsible for funding the hijackers.

A trader on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange holds his head early in the trading day as the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell nearly 500 points in early trading 17 September, 2001. (File/AFP)

Few of these wild allegations had any truth to them, but the damage was done. Americans were increasingly reluctant to do business with the Middle East, for fear of sanctions by their own governments and for reasons of pure xenophobia as the “war on terror” began to accelerate. US exports to Saudi Arabia fell by 25 percent in the first nine months of 2002.

It was a two-way street of distrust. In August 2002, the Financial Times reported that “disgruntled Saudis have pulled tens of billions of dollars out of the US, signaling a deep alienation from the USA.”

Though these developments were worrying for global trade and financial flows, there was an immediate benefit for the economies of the Gulf. Middle East capital, which had previously looked to the US for maximum return, instead began to seek investment opportunities at home.

A trader on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange talks on a phone halfway as Wall Street reopened 17 September, 2001 after a four-day closing due to last week's terrorist attacks. (File/AFP)

Despite the invasion of Afghanistan in late 2001 and the US coalition-led attack on Iraq in 2003, the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks was a boom time for financial markets in the Middle East, as capital was repatriated and oil prices surged on worries about tight supply in the tense security situation.

By the time President George W. Bush stood on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln in May 2003 and declared “Mission Accomplished” in Iraq, the Saudi stock market was up nearly 12 percent on the year, and went on to greater heights later that year as the first phase of the Iraq war drew to a close.

“Arab relations with the US may have been strained but the removal of Saddam Hussein was a widely shared objective that seemingly removed the threat of wider regional conflict,” the banker told Arab News.

A street sign near the front of the New York Stock Exchange August 5, 2011. (File/AFP)

That hope of a US-led period of peace and liberal democracy in the Middle East proved illusory by subsequent events, and it is in these that we discern the long-term economic significance of the 9/11 attacks.

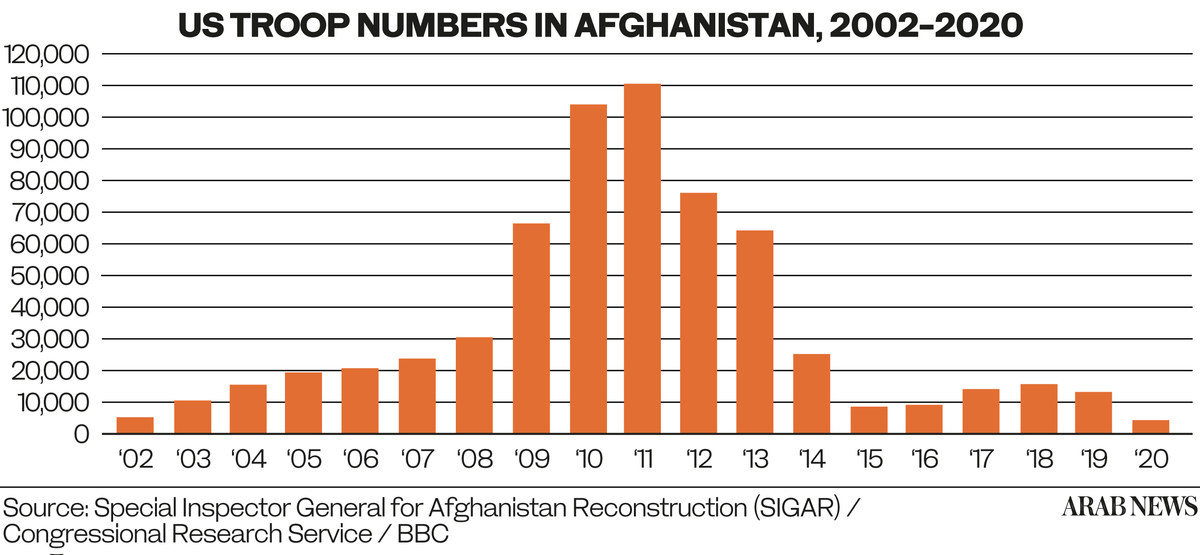

The “forever wars” in Afghanistan and Iraq that President Joe Biden is only now bringing to an end caused endless human suffering in the Middle East, destabilizing other Arab states and contributing to the chaos of the Arab Spring in 2011. But they also had a direct effect on the global economy.

“The US spent unimaginable sums trying to force its lifestyle and politics on Muslim countries,” Anthony Harris, a former British ambassador to the UAE who is now a Gulf-based businessman, told Arab News.

“The exact amounts will never be known, but the Afghan and Iraqi wars probably cost America about a trillion dollars each for each decade of these campaigns, or upwards of $4 trillion in all.

“Debts on such a vast scale have impacted financial markets and benefited those who run trade surpluses with the US, like China and some of the Arab oil producers.”

In this view of post-9/11 events, the attacks on New York and elsewhere contributed significantly to the cheap debt conditions which contributed to the global financial crisis in 2008/09, and still have a legacy in the “quantitative easing” programs virtually every central bank in the world espouses to help get their economies out of the COVID-19 recession.

They have also fed the growing trade tensions between the US and China.

One other legacy of the attacks is also worth noting. The febrile atmosphere of post-9/11, when the whole Middle East was regarded virtually as an enemy by Washington, provided the first impetus to the revolution in American oil production techniques. Consequently, the US would become self-sufficient in crude production, but global energy markets would be destabilized and economies of the Middle East affected.

In economics, finance and energy, as in politics, the Al-Qaeda attacks on the US on Sept. 11, 2001, were transformational events. Two decades on, the global economy is still living with the consequences.

Twitter: @FrankKaneDubai