ISLAMABAD: The Pakistani rupee plunged to another all-time low of Rs 170.48 against the United States dollar on Wednesday, mainly due to concerns that a US Senate bill seeking sanctions on the Afghan Taliban could be extended to Pakistan, dealers and analysts said.

The rupee lost 51 paisas, or 30 percent percent of its value, against the greenback as the demand for the dollar continued to build pressure, according to the central bank.

The rupee was trading at Rs 172.50 for selling and Rs 171.50 for buying in the open market on Wednesday, according to the Exchange Companies Association of Pakistan.

“The plunge appeared to be related to the US Senate bill seeking to impose sanctions on the Afghan Taliban and which could extend to Pakistan,” Dawn newspaper reported.

The bill, backed by 22 senators, also seeks to investigate Pakistan’s support for the Taliban over the past 20 years.

It is not clear what likelihood the US bill has of becoming law.

The dollar hit a high of Rs168.43 in August last year. Then it started declining and reached Rs151.83 on May 14, 2021. However, the greenback started rising once again and has appreciated by 6.6 percent and 9.9 percent since June and May 14, 2021, respectively.

The State Bank of Pakistan had indicated earlier that the dollar could appreciate during the current financial year due to an expected higher current account deficit.

Pakistani rupee hits record low on concern about US sanctions

https://arab.news/nqyfw

Pakistani rupee hits record low on concern about US sanctions

- Pakistani currency plunges to another all-time low at Rs 170.48 against the US dollar

- Dip due to concerns US sanctions on the Afghan Taliban could be extended to Pakistan

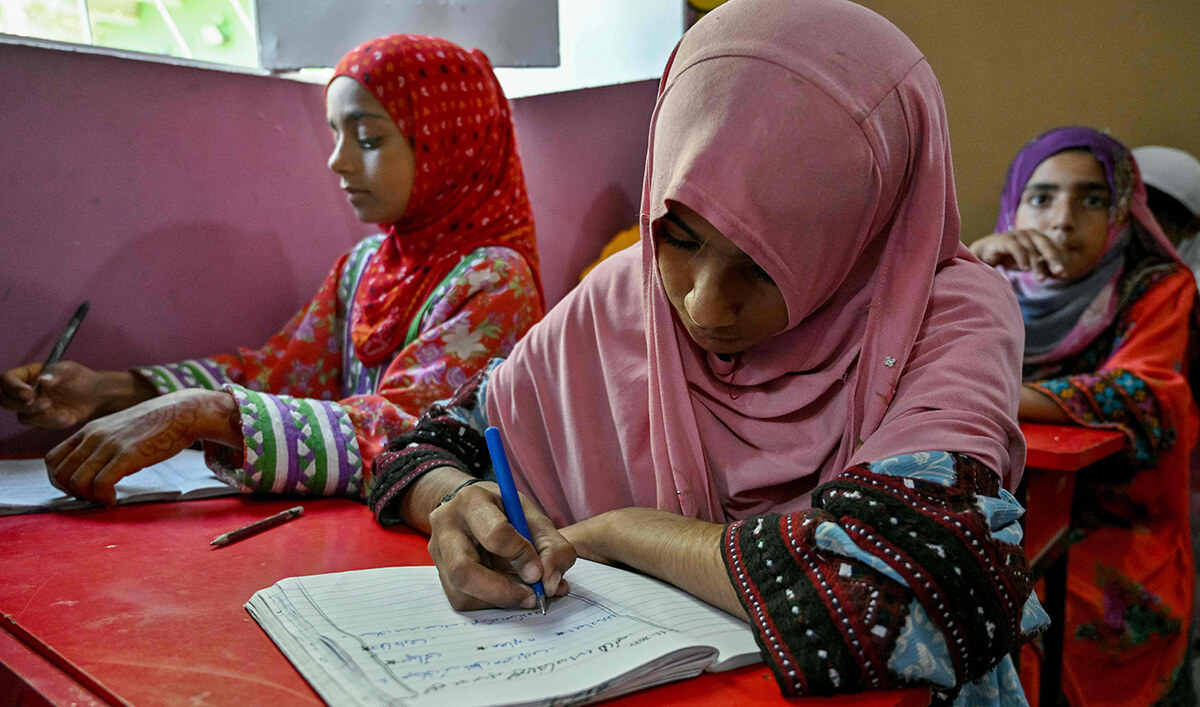

‘Education apartheid’: schooling in crisis in Pakistan

- Pakistan is facing severe education crisis, with over 26 million children out of school, the majority in rural areas

- Poverty is the biggest factor keeping children out of classrooms, but the problem is worsened by other factors too

ABDULLAH GOTH: Aneesa Haroon drops off her tattered school bag at her rural home in Pakistan and hurriedly grabs lunch before joining her father in the fields to pick vegetables.

The 11-year-old’s entry into school at the age of seven was a negotiation between teachers and her parents in her farming village on the outskirts of Karachi.

“Initially, many parents were not in favor of educating their children,” headteacher Rukhsar Amna told AFP.

“Some children were working in the fields, and their income was considered more valuable than education.”

Pakistan is facing a severe education crisis, with more than 26 million children out of school, the majority in rural areas, according to official government figures — one of the highest rates in the world.

This weekend, Pakistan will host a two-day international summit to advocate for girls’ education in Muslim countries, attended by Nobel Peace laureate and education activist Malala Yousafzai.

In Pakistan, poverty is the biggest factor keeping children out of classrooms, but the problem is worsened by inadequate infrastructure and underqualified teachers, cultural barriers and the impacts of climate change-fueled extreme weather.

In the village of Abdullah Goth on the outskirts of Karachi, the non-profit Roshan Pakistan Foundation school is the first in decades to cater to the population of over 2,500 people.

“There was no school here for generations. This is the first time parents, the community and children have realized the importance of a school,” said Humaira Bachal, a 36-year-old education advocate from the public and privately funded foundation.

Still, the presence of a school was just the first hurdle, she added.

Families only agreed to send their children in exchange for food rations, to compensate for the loss of household income that the children contributed.

In Abdullah Goth, most children attend school in the morning, leaving them free to work in the afternoon.

“Their regular support is essential for us,” said Aneesa’s father, Haroon Baloch, as he watched his daughter and niece pick okra to sell at the market.

“People in our village keep goats, and the children help graze them while we are at work. After finishing grazing, they also assist us with labor tasks.”

Education in Pakistan is also increasingly impacted by climate change.

Frequent school closures are announced due to heavy smog, heatwaves and floods, and government schools are rarely equipped with heating or fans.

In the restive provinces of Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, education faces significant setbacks due to ongoing militancy, while classes are routinely disrupted in the capital Islamabad due to political chaos.

Although the percentage of out-of-school children aged between five and 16 dropped from 44 percent in 2016 to 36 percent in 2023, according to census data, the absolute number rises each year as the population grows.

Girls all across the country are less likely to go to school, but in the poorest province of Balochistan, half of girls are out of school, according to the Pak Alliance for Maths and Science, which analyzed government data.

Cash-strapped Pakistan’s Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif declared an “education emergency” last year, and said he would increase the education budget from 1.7 percent of GDP to 4 percent over the next five years.

Public schools funded by the government offer free education but struggle with limited resources and overcrowding, creating a huge market for private schools whose costs can start from a few dollars a month.

In a parallel system, thousands of madrassas provide Islamic education to children from the poorest families, as well as free meals and housing, but often fail to prepare students for the modern world.

“In a way, we are experiencing an education apartheid,” said Adil Najam, an international relations professor at Boston University who has researched Pakistan’s education system.

“We have at least 10 different systems, and you can buy whatever quality of education you want, from absolutely abysmal to absolutely world-class.

“The private non-profit schools can prime the pump by putting (out) a good idea, but we are a country of a quarter billion, so these schools can’t change the system.”

Even young student Aneesa, who has set her mind on becoming a doctor after health professionals visited her school, recognizes the divide with city kids.

“They don’t work in field labor like we do.”

In the small market of Abdullah Goth, dozens of children can be seen ducking in and out of street-side cafes serving truck drivers or stacking fruit in market stalls.

Ten-year-old Kamran Imran supports his father in raising his three younger siblings by working at a motorcycle workshop in the afternoons, earning 250 rupees ($0.90) a day.

Muhammad Hanif, the 24-year-old owner of the workshop, does not support the idea of education and has not sent his own children to school.

“What’s the point of studying if after 10 to 12 years, we still end up struggling for basic needs, wasting time and finding no way out?” he told AFP.

Najam, the professor, said that low-quality education was contributing to the rise in out-of-school children.

Parents, realizing their children cannot compete for jobs with those who attended better schools, instead prefer to teach them labor skills.

“As big a crisis as children being out of school is the quality of the education in schools,” said Najam.

Rights network criticizes flood compensation and rehabilitation efforts in Sindh

- Network’s fact-finding team says not much consultation was done while designing houses for flood-hit families

- It says these one-room ‘flood-resilient’ structures lack basic amenities like toilets, can’t withstand heavy rain

KARACHI: A fact-finding mission conducted by a network of rights activists in South Asia on Friday criticized Pakistan’s response to the devastating 2022 floods, highlighting significant shortcomings in housing, sanitation and health care for flood-affected communities in Sindh.

The 2022 floods, triggered by unprecedented monsoon rains and glacial melt, displaced millions, killed over 1,700 people and caused damages exceeding $35 billion, leaving vast areas submerged for months.

The fact-finding team of South Asians for Human Rights (SAHR) visited Sindh, surveying several districts, including Larkana, Shikarpur, Nawabshah and Hyderabad, from January 6-10 to assess the government’s compensation and rehabilitation efforts.

“The preliminary findings contradict the provincial government’s claims of launching one of the world’s largest housing projects for flood affectees,” said Ahmad Rafay Alam, an environmental lawyer and SAHR Bureau Member, during a press conference in Karachi.

The mission raised serious concerns over the proposed one-room “flood-resilient” housing model, calling it insufficient and lacking essential amenities such as kitchens and toilets.

“With skyrocketed inflation, the Rs300,000 ($1,077) compensation per house is unreasonably low,” SAHR said in a statement.

It maintained there was not much consultation while designing the houses, questioning their climate resilience and warning they were unlikely to survive future disasters.

“More severe natural calamities will impact this vulnerable population, and it is highly unlikely that these structures can withstand another heavy rain,” it noted.

In Dhand, a village near Mohenjo Daro, SAHR found that only four out of 40 destroyed houses had been rebuilt.

“Some families still live in tents or neighbors’ homes, and with average family sizes of six people, it is impossible to live in these single rooms, especially when some family members are married,” it said.

The regional rights network urged the government to conduct fresh surveys to ensure no genuinely affected individuals were left out. It informed that many residents had reported difficulty in finding their names on government beneficiary lists, delaying relief.

SAHR also highlighted poor sanitation and health care in affected areas, reporting that villages lacked drainage systems, leading to outbreaks of diarrhea, malaria and skin infections.

Arab News reached out to provincial officials, including Sindh’s Information Minister Sharjeel Memon and Chief Minister Murad Ali Shah’s spokesperson Rasheed Channa, but received no response.

Sadia Javed, another government spokesperson, said she would review the mission’s findings but had not responded by the time of filing this report.

Pakistan court halts Afghan musicians’ repatriation for two months, orders decision on asylum cases

- Afghan musicians feared persecution and fled their country after the Taliban’s return to power in 2021

- They filed a petition in the Peshawar High Court last year amid the government’s deportation campaign

PESHAWAR: A Pakistani court issued a short order on Friday, barring the forced repatriation of about 150 Afghan singers and musicians who fled their country after the Taliban’s return to power in 2021 and directing federal authorities to determine their status within two months.

The Peshawar High Court (PHC) issued the order after the musicians filed a petition last year, seeking asylum amid fears of persecution in their home country.

The Taliban had imposed a strict ban on music during their first stint in power from 1996 to 2001, suppressing musical expression and leading to the persecution of artists across Afghanistan.

A single-member bench of Justice Wiqar Ahmad issued a two-page short order, accepting the plea of the musicians and restraining the government from forcibly repatriating them to Afghanistan.

“The Federal Government or its notified officer shall decide cases of all these petitioners for grant or refusal of asylum within a period of two months,” the PHC order said.

“Till the final decision, these petitioners shall not be ousted from the territory of Pakistan nor otherwise compelled to leave Pakistan and go back to their native country Afghanistan,” it added.

Afghan nationals in Pakistan have lived in a state of uncertainty since 2023, when the government launched a major deportation drive against migrants living illegally in the country. The campaign primarily targeted Afghans amid an uptick in militant violence, with the government alleging that several of them were involved in attacks on Pakistani civilians and security forces.

The Afghan authorities in Kabul denied the allegations, saying their citizens were not responsible for Pakistan’s security challenges.

The court order said if the federal authorities were unable to decide the cases within 60 days, the interior ministry’s secretary should issue permission allowing the petitioners to stay for a period sufficient to reach a final decision.

“Law Enforcement Agencies of the Federal Government as well as the Provincial Government are restrained from taking any adverse action against these petitioners for their stay in Pakistan for a period of 60 days or such extended time if allowed by the Federal Government,” it added.

Afghan musicians described the court order as a “ray of hope,” saying the recent crackdown on their fellow nationals had sent shockwaves through their community.

“We were in fear, but the recent decision of the court has sparked happiness among our community,” Zarwali Afghan, a musician from Afghanistan, told Arab News. “We hope that the government will consider our cases on humanitarian grounds.”

The Afghan Taliban hold the belief that music is forbidden in Islam, though several schools of thought within the religion differ with their interpretation.

Last year, authorities in Kabul were compelled to clarify their stance after their diplomats in Pakistan and Iran refrained from standing during the playing of national anthems at official ceremonies.

The incident was perceived by both countries as disrespectful and contrary to diplomatic norms. However, the Afghan Taliban explained that their representatives meant no harm and would have stood if the national anthems had been played without background music.

Arab News attempted to seek a response from the interior ministry over the court order, but its spokesperson did not respond.

Pakistani PM, OIC chief urge global push for Gaza ceasefire

- The OIC leader is currently in Islamabad to attend a global conference on girls’ education in Muslim countries

- Shehbaz Sharif also met with the secretary general of the Muslim World League, the co-host of the conference

ISLAMABAD: Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) Secretary General Hissein Brahim Taha agreed on Friday the OIC must intensify pressure on the international community to secure an immediate ceasefire in Gaza during their meeting in Pakistan’s federal capital.

The top OIC official arrived in Islamabad earlier in the day to attend a two-day global conference on girls’ education in Muslim countries, set to begin on Saturday. He was received by Education Minister Khalid Maqbool Siddiqui upon arrival.

During the meeting, the prime minister thanked the OIC for its consistent support regarding the Kashmir dispute with his country’s nuclear rival, India.

Sharif strongly condemned Israel’s ongoing “genocidal campaign” in Gaza and stressed the need for an immediate and unconditional ceasefire, unrestricted humanitarian aid for Palestinians and global accountability for Israel’s conduct of war.

“Both leaders agreed that the OIC must maintain its pressure on the international community for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza,” read an official statement released by Sharif’s office after the meeting. “They emphasized that the resolution of the Palestine issue must align with UN resolutions and the aspirations of the Palestinian people.”

The meeting also touched on combating Islamophobia and other global and regional matters of mutual interest.

GIRLS’ EDUCATION

The OIC secretary general expressed gratitude for Pakistan’s warm reception and praised the country’s leadership role in addressing critical issues facing the Muslim world.

“The hosting the international conference on girls’ education in the Muslim world is an example of Pakistan’s leadership role in addressing important issues,” he said.

Separately, the prime minister also met with Sheikh Dr. Mohammad bin Abdulkarim Al-Issa, the secretary general of the Muslim World League (MWL).

Sharif commended the MWL’s partnership in co-hosting the two-day conference and emphasized that the event would send a strong global message about the Muslim world’s commitment to advancing girls’ education.

Dr. Al-Issa informed Sharif the conference would culminate in the Islamabad Declaration, a consensus document promoting girls’ education in Muslim countries.

He also informed the conference would feature renowned scholars, educators, and thought leaders from around the globe to address a wide range of issues affecting the Muslim world.

Stitching hope: Sindh’s artisan program uplifts rural women through handicrafts

- The Sindh Rural Support Organization has trained over 6,000 women in some of the poorest areas in Pakistan’s south

- Woman artisans in Sindh say the organization has not just brought them financial stability, but dignity and hope as well

KARACHI: Dressed in a vibrant pink embroidered dress with traditional patterns depicting the Sindhi culture, Ponam Shaam Lal proudly displays her handcrafted cushions to visitors at an upscale mall in Karachi. Had it not been for Sindh’s rural artisan programs, Lal, in her late 30s, would have been bereft of skill, and the means to earn her bread and butter.

Lal’s creations were among the 5,800 handicrafts showcased at a four-day exhibition launched by the Sindh Rural Support Organization (SRSO), a not-for-profit organization, in Karachi’s Ocean Mall on Thursday. The event, a collaboration with the Sindh government, featured 3,545 rural woman artisans displaying products ranging from traditional shawls to embroidered accessories.

The SRSO has trained thousands of rural women in different trades from some of the most under-developed regions of Sindh such as Jacobabad, Kandhkot-Kashmore, Shikarpur, Ghotki, Qambar-Shahdadkot and Badin districts in the last 16 years.

Lal, who rarely ventured beyond her remote village near Rohri up until a few years ago, is one of those thousands of artisans at the Karachi event, which aims to help these women sell to high-end customers in Pakistan’s urban cities.

“Before, we never went out; we didn’t know the outside world. Only my husband would earn. We would sit idle, wondering how to make ends meet or pay for our children’s education,” Lal told Arab News, as she showed her handicrafts to a customer.

“We were poor, but when we started doing this work, took on orders, and worked hard, our circumstances improved.”

Lal says the crochet and embroidery work she learned due to the SRSO’s training program has helped her send her children to school, and life is “finally stable.”

Shahida Baloch, an artisan and trainer from Sindh’s Sukkur city, learned embroidery from her mother and grandmother, but she had little formal education or access to markets where she could sell her products.

“I am a rural woman from the village,” Baloch, a mother of seven, told Arab News.

“We learned embroidery and sewing at home from our grandmothers, without attending any institute or training center.”

But things changed for Baloch, when the SRSO reached her village almost a decade ago. She says the organization provided her recognition for her embroidery and sewing skills by showcasing her work at exhibitions across the country.

As one of the few trainers at the SRSO, Baloch now guides woman artists on how to transform traditional craft into marketable products.

“I trained women to make cushions, bags, and pouches from the same art. We also worked on color combinations, blending traditional Sindhi colors — blue, yellow, red, green, all natural colors — with modern preferences. This way, the color became more appealing to urban customers,” she said.

“Similarly, we taught them to create buttons as a supplementary product. For instance, if no one buys large, embroidered fabrics worth fifty thousand or a hundred thousand rupees, they might buy a few buttons to embellish their shirts.”

SRSO CEO Muhammad Dittal Kalhoro said the organization has trained over 6,000 women in Sindh’s poorest areas through 316 Business Development Groups.

“Our aim is to connect these women with high-end markets and ensure better incomes,” he said.

Sindh government spokesperson Sadia Javed said the SRSO, part of a larger poverty-reduction initiative, provides loans and support to woman artisans, and with a 98 percent repayment rate, it has proven highly effective.

“Earlier, this program was limited to a few districts,” Javed said. “Now, it has expanded to urban slums in Karachi and Sukkur.”

For women like Lal and Baloch, the SRSO has brought more than financial stability.

It has brought them dignity and hope.

“I am extremely grateful to Allah for making the SRSO the means through which I was empowered,” said Baloch, who could not study beyond the fifth grade, but has managed to send two of her daughters to university.

“Today, I am successful, and so are my children.”