RAWALPINDI: Saadia Ahmed worked for years as an entertainment journalist for an online magazine until the publication shut down shortly after the emergence of the coronavirus pandemic last year.

The 35-year-old correspondent was “devastated,” she said, as she saw massive job losses all around the world. But rather than wait for the entertainment journalism business to pick up again, Ahmed decided to move in a different direction.

“At first, I thought I should start writing a book, but then I felt too depressed to work on a project like that,” she told Arab News over the phone from Perth, Australia, where she is based. “Ultimately, I decided to take the advice of a friend who suggested that I should launch my own YouTube channel.”

Armed with a selfie stick and her intuition, Ahmed started making and uploading videos three times a week, focusing on developments around the world and discussing rights issues on a channel called “My Two Cents.”

“Since then, there has been no looking back,” said Ahmed, who was selected for an MPhil degree program on the basis of her broadcasts. Indeed, the pandemic had changed the course of her life.

The economic collapse caused by the coronavirus has put millions of economic futures in doubt. Ahmed is only one of millions of people around the world who have been faced with this quandary: Wait for business and employment to pick up, or leave try something new?

“Sometimes you need to burn the boats,” Ahmed said. “I wasn’t courageous enough to do that on my own, but the shutting down of the magazine did it for me. If you can, you must go for it too.”

Saadia Ahmed addresses a storytelling session in Australian on July 4, 2021. (Photo courtesy: Saadia Ahmed/Instagram)

Several other Pakistanis have made similar choices.

Journalist Mehr F Hussain recalled the exact moment the contagion changed her life.

“I was standing outside my door at night, staring at the bolted gate,” she told Arab News. “I told myself, ‘This is it; this is all it takes to strip us of our lives.’”

After many years of finding Pakistan’s publishing industry frustrating, Hussain took the reprieve offered by the pandemic to “jump the proverbial cliff” and launch her dream project: an independent publishing platform called Zuka Books.

“It was an act of creative resistance to what was happening around me,” she said. “It was a move for liberation from the old guard. Basically, it was a massive farewell to the pre-pandemic life I led.”

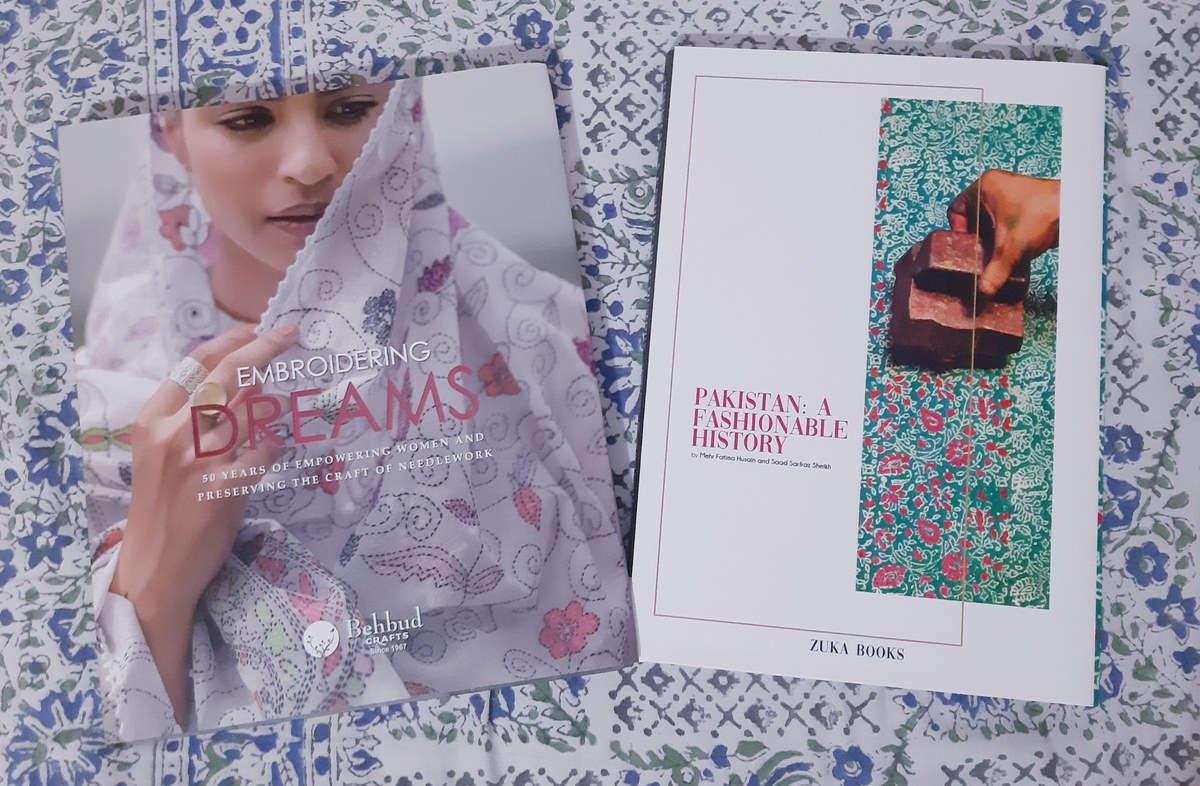

Hussain’s publishing house has published a fashion coffee table book, a graphic novel and a book of poetry, among others.

“I wish I had taken this decision earlier,” she said. “I wish I had been more proactive before the pandemic, but it takes a journey to get to a destination. I feel I made the right decision at the right time and I am lucky to have done so.”

The image shows the books published by Zuka Books. (Photo courtesy: @mfhusayn/Twitter)

The pandemic also gave 30-year-old corporate executive Sundar Waqar a second lease of life, making her abandon a nine-to-five job at a corporate firm and establish a business selling allergen-free food and baked items.

Waqar, who was diagnosed with Celiac disease which prevented her from consuming gluten, realized during the pandemic that she could do something for so many others like her who who faced dietary restrictions.

“I have been making food for myself for years and have met people who faced difficulties in finding gluten-free food, so I decided to start this,” she told Arab News, saying the pandemic was the catalyst to devoting herself fully to launching a gluten-free food business in Karachi.

“I am so glad I did it,” she said. “I cannot stress enough that if you want to change something in your life or career, no matter how drastic, you should take the plunge. It is scary and has its own challenges, but it is definitely worth it.”

Fiscal consultant Jasir Shahbaz, 26, who left his job to teach economics, echoed the sentiment.

“When you are working from home, it is just you and what you do to make a living,” he said. “That’s also when you begin to ask yourself if the work you do is what you truly imagined for yourself.”

“Without this time to reflect, I would have continued in that job for a long time,” he added, saying the pandemic forced him to reckon with uncertainty and let go of all the hangups that had hindered him from pursuing teaching as a career.

“There has always been this negative perception about teaching in Pakistan, that it is not the most preferred career trajectory for men,” he said. “I decided to let it go.”

A year into his decision, Shahbaz said he felt “great” about his new job, which was a “stark contrast” to the previous one in terms of his sense of fulfilment.

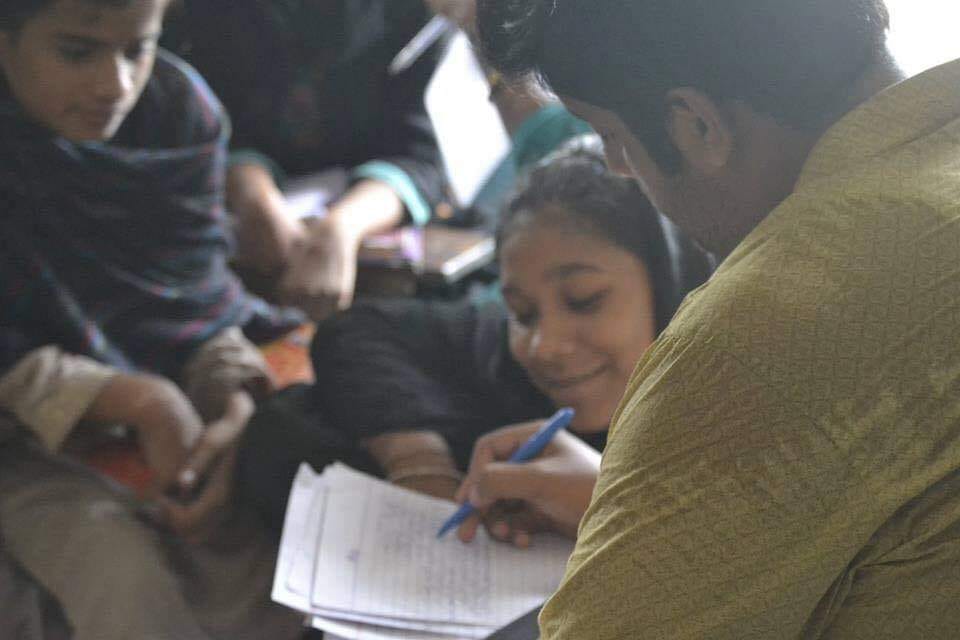

The picture shared on March 7, 2021 shows Jasir Shahbaz teaching creative writing to students in Green Town, Lahore, Pakistan. (Photo courtesy: Jasir Shahbaz/Facebook)

Publisher Hussain agreed, saying she was not surprised that so many people had made transformative decisions in the “moment of anxiety” offered by the pandemic.

“If the pandemic has done anything,” she said, “it is to make us realize how important it is to live a better and more conscious life.”