TALKING HORSES

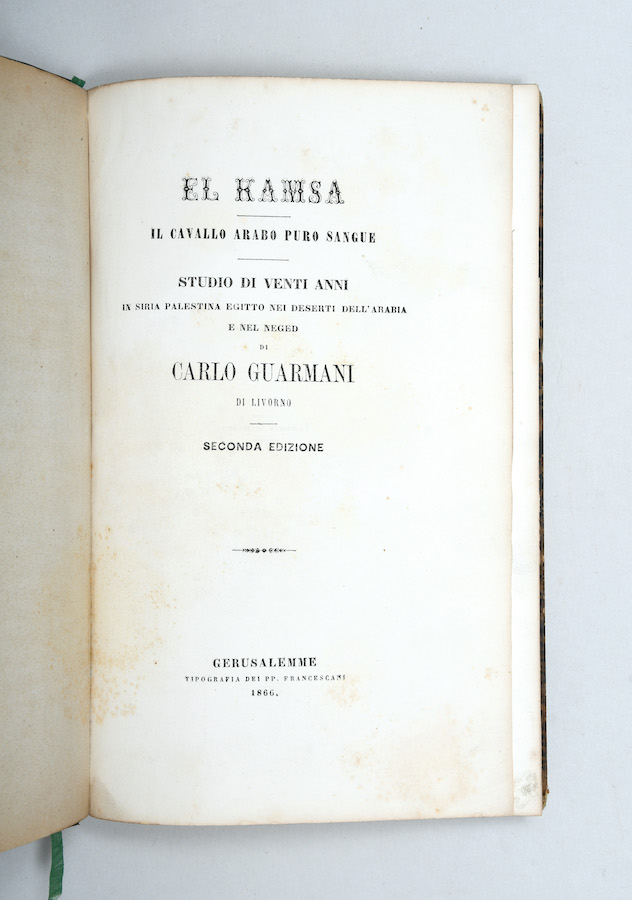

Carlo Guarmani’s “El Kamsa” from 1866, the double-volume “Breeding of Pure Bred Arab Horses” and a “History of The Royal Agricultural Society’s Stud of Authentic Arabian Horses” — both produced by The Royal Agricutural Society of Egypt in the 1930s and 1940s — all offer fascinating insights into the history of the pure-bred Arabian horse. The RASE’s books chronicle the society’s efforts to halt the extinction of this cultural icon — efforts supported extensively by Saudi Arabia.

Guarmani’s book, meanwhile, is considered one of the finest early Western works on the the subject of Arabian horses, not least because it includes translation’s of “three key Arabic works, most importantly that of one Ahmed, described by Guarmani as ‘the main hippologies of the century,’ director of the stables under Abdullah Pasha ibn Ali, Ottoman governor of the Eyalet of Sidon from 1820-32,” according to Peter Harrington’s catalogue.

Guarmani was an Italian horse expert and dealer who travelled to the region in 1850, spending 16 years in Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and the Arabian desert and becoming fluent in Arabic. He was tasked with finding pure-bred Arab stallions to buy for the French and Italian military. “Several months later, and after several risky adventures, Guarmani ‘successfully purchased three prime stallions for the exorbitant price of 100 camels.’ This second edition adds his narrative of this journey,” the catalogue states. “The title, ‘El Kamsa,’ refers to the five great families of the Arab horse.”

LANGUAGE LESSONS

The bookseller describes this collection of seven Khaleeji Arabic handbooks as “a highly unusual gathering of these extremely scarce language guides.” They were written in the 1940s to 1960s for employees of the various foreign oil companies expanding their operations in the region after the Second World War — particularly Aramco in Saudi Arabia, the Bahrain Petroleum Company, and the Kuwait Oil Company.

Aramco’s “Arabic Work Vocabulary for Americans in Saudi Arabia” is, the catalogue says, “the first to cover the Qatifi dialect, usages in Hofuf, Bahrain and Jubail, with some accommodation to the Bedu as well.” It also includes some cultural tips, including: “The Westerner's tendency to dispense with formalities can often be unintentionally offensive.” Only six copies of this edition are recorded in libraries around the world.

The Kuwait Oil Company’s effort covers similar ground, with tips on how to converse in “the bazaar, the harbor, stores, the refinery etc.” and exercises on local geography and climate, pearl diving, fishing and boat building, while Bapco’s “Colloquial Arabic” text book for employees is “grouped into eight lessons themed around working with local staff in Bahrain: in the workplace, greetings and small talk, an interview, construction, transportation, in the shop, troubles.”

A SPY’S ACCOUNT

Max Oppenheim journeyed from Cairo through northern Mesopotamia at the beginning of the 20th century. Officially, he was on an expedition to establish the route of the Baghdad Railway. In reality, he was a spy for Kaiser Wilhelm II, the German emperor. Oppenheim is described as “one of the most colorful figures of Middle Eastern politics and archaeology … an orientalist and ardent believer in his country’s destiny in the East. He travelled extensively through Mesopotamia and Syria, then Ottoman territories, mapping and taking meticulous notes on everything, from the lie of the land to the number of tents and houses owned by every tribe and village.” His journey took him through Beirut, Damascus, Palmyra, Mosul, Baghdad, Muscat, Adan, Zanzibar and more.

A SECRET SOCIETY’S ENCYCLOPEDIA

Hailed as “one of the most complete medieval encyclopedias of science,” this is a translation of a collection that was “composed sometime between the 10th and 11th centuries by an enigmatic and remarkable group of anonymous authors based in Basra known collectively as Ikhwān al-Safā' or Brethren of Purity.” A British historian has said they “ransacked every faith, every philosophy; ‘no science and no method is to be despised,’ they said; no part of knowledge, no attempt to reach truth, was common or unclean to them … Its value lies in its completeness, in its systematizing of the results of Arabian study.” The 52 “treatises” cover maths, theology, psychology, the natural sciences and more.

A VITAL GUIDE TO FARMING

Author Ibn Al-‘Awwam was “an Arab agriculturist who flourished at Seville in southern Spain in the later 12th century.” This guidebook is described as “the most comprehensive treatment of (agriculture) in medieval Arabic, and one of the most important medieval works on the subject in any language.” It was “for a long time the only source of reference on medieval Andalusi agronomy.” Al-‘Awwam breaks his topic down in great detail, covering crops and livestock. “The book describes the cultivation of 585 different plants, and gives cures for diseases of trees and vines, as well as diseases and injuries to horses and cattle.”

A RARE MAP OF THE REGION

This 1935 work is the final edition of Frederick Fraser Hunter’s “landmark Map of Arabia.” Hunter produced it as an accompaniment to J.G. Lorimer’s acclaimed “Gazetteer of the Gulf, Oman and Central Arabia,” written in the early 20th century, which remains “an important tool for researchers.” Hunter based his work on oil company and geologists’ surveys, travelers’ accounts, existing maps, and “local native information.” The result was “a milestone in the map-making of the Arabian peninsula,” an “extremely scarce and meticulous” work of which just four of this version are listed on library catalog WorldCat.