The forgotten Arabs of Iran

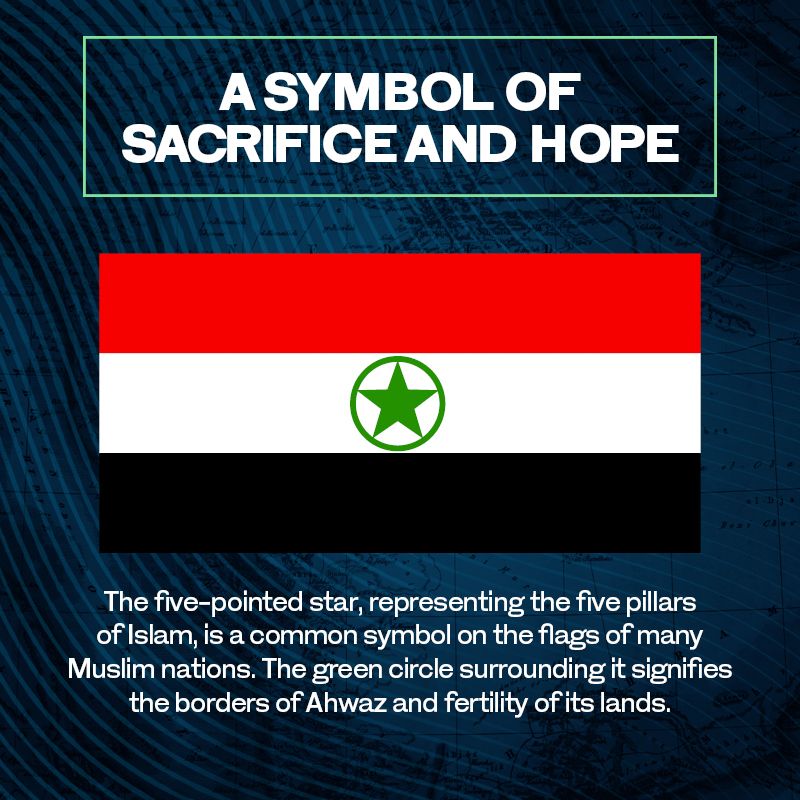

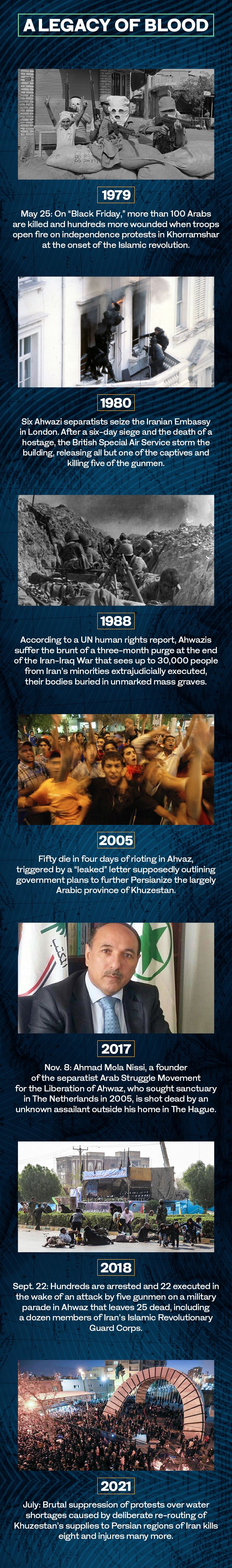

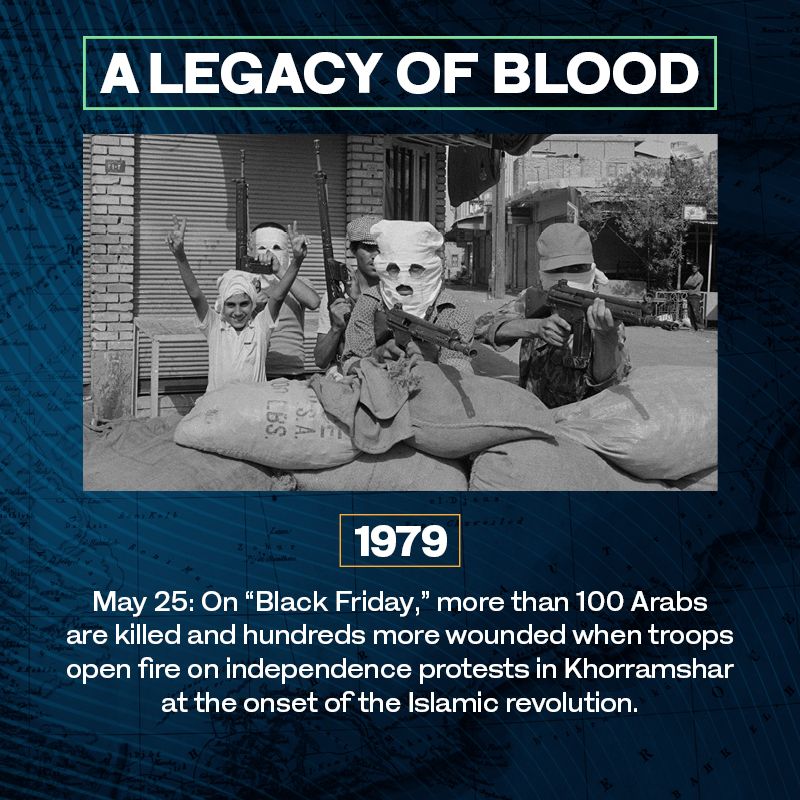

A century ago, the autonomous sheikhdom of Arabistan was absorbed by force into the Persian state. Today the Arabs of Ahwaz are Iran's most persecuted minority

“My dear son, when you grow up, you will come here like your father — this is the fate of all Ahwazis”

On Jan. 23, 2021, three Arab men on death row in Sepidar prison in the Iranian city of Ahvaz sewed their lips shut at the start of a hunger strike in protest at their conditions and the threat of execution hanging over them.

Just over a month later, on Feb. 28, 2021, they were executed in secret.

Jasem Heidary, Ali Khasraji and Hossein Silawi were members of Iran’s Ahwazi Arab minority. They had been accused of involvement in an attack on a police station in Ahvaz in May 2017, but human rights groups said their “confessions” had been extracted under torture.

Jasem Heidary, Ali Khasraji and Hossein Silawi: hanged in February 2021 after confessions extracted under torture.

Jasem Heidary, Ali Khasraji and Hossein Silawi: hanged in February 2021 after confessions extracted under torture.

The fate of the three men reflected the reality of a century of systematic persecution of the Ahwazi in Iran.

The Ahwazi are an ethnic minority whose very existence, let alone the extent of the persecution they suffer, is not widely known. Numbering an estimated 8 million to 9 million people, they are the descendants of the original Arab occupants of an area that today is part of Iran, but which for hundreds of years was known as the Emirate of Arabistan.

Al-Ahwaz, as the Ahwazi call their lost state, ran along the Iranian side of the Shatt Al-Arab and down the east shore of the Gulf, an area roughly equivalent to the modern Iranian province of Khuzestan, but also including parts of the provinces of Elam, Bushehr and Hormozgan.

In this map, published by the National Liberation Movement of Ahwaz, the claimed territory of Al-Ahwaz is shown as extending over 1,300 kilometers, displacing Iran from the whole of the eastern side of the Arabian Gulf.

In this map, published by the National Liberation Movement of Ahwaz, the claimed territory of Al-Ahwaz is shown as extending over 1,300 kilometers, displacing Iran from the whole of the eastern side of the Arabian Gulf.

In the 19th century, in a political deal over borders, Arabistan was signed over to Persia by the Ottoman empire, but even then the emirate largely retained its autonomy.

Until, that is, oil was discovered in the region.

What would be a blessing for the Arabs of the western Gulf proved to be a curse for those on the far shore. In 1925, following the discovery of its great resources, Arabistan was brought by force under central Iranian control.

Since then, Iran, under both the monarchy and the revolutionary regime that replaced it in 1979, has worked to eradicate Ahwazi culture, banning Arabic in schools, stripping the region of its natural resources and attempting to “Persianize” the population.

This exercise in social engineering is reflected in the changed names of towns, cities and, indeed, the entire region. To the Ahwazi, Khuzestan will always be Al-Ahwaz. The Iranian port city of Khorramshahr at the head of the Gulf was founded by the Arabs as Mohammerah. To the Ahwazi, the eponymous city of “Ahvaz,” upstream from Khorramshahr on the Karun river, is Ahwaz.

Shipping in the busy Iranian port of Khorramshahr, formerly the Arab city of Mohammerah, pictured in 1976. (Getty Images)

Shipping in the busy Iranian port of Khorramshahr, formerly the Arab city of Mohammerah, pictured in 1976. (Getty Images)

For almost a century, Iran’s oppressed Arabs have dreamt of forming a breakaway independent nation, or at least of recovering a degree of autonomy, perhaps within some form of federalist Persian state.

Today, however, despite decades of struggle and the sacrifices of countless dissidents and human rights activists, the Ahwazi are as far from realizing their dream of freedom as they have ever been.

“Seven reasons why I should die”

In July 2012, 32-year-old Ahwazi activist Hashem Shabani and fellow teacher Hadi Rashedi, 38, were sentenced to death for the crimes of “Moharebeh” (waging war against God) and “Ifsad fel Arz” (corruption on Earth) — two charges typically laid against anyone Iran considers to be a dissident.

According to Iran Human Rights, the only “crime” of which the two men were guilty was having co-founded Al-Hiwar, a cultural institute set up to promote Arabic education among deprived Ahwazi youth.

Executed: Hashem Shabani and Hadi Rashedi

Executed: Hashem Shabani and Hadi Rashedi

Throughout the two years the men spent in prison before they were hanged, both were tortured into signing worthless confessions falsely linking them to a terrorist organization.

In a letter written in prison, Shabani confessed only to having written essays critical of Iran’s treatment of its minorities, including “hideous crimes against Ahwazis, particularly arbitrary and unjust executions.”

Throughout it all, he added, “I have never used a weapon — except the pen.”

With that pen, while in prison he wrote the following poem, “Seven reasons why I should die”:

“For seven days they shouted at me:

You are waging war on Allah!

Saturday, because you are an Arab!

Sunday, well, you are from Ahvaz!

Monday, remember you are Iranian!

Tuesday, you mock the sacred Revolution!

Wednesday, didn’t you raise your voice for others?

Thursday, you’re a poet and a bard!

Friday: You’re a man, isn’t that reason enough to die?”

Shabani’s letters and poems were smuggled out of prison after his death and translated into English by Rahim Hamid, a fellow Ahwazi, and a student of both Shabani and Rashedi who would only narrowly escape their fate.

Ahwazi journalist Rahim Hamid, who escaped the fate of his executed teachers and found sanctuary in the US.

Ahwazi journalist Rahim Hamid, who escaped the fate of his executed teachers and found sanctuary in the US.

Hamid was a 22-year-old studying English at Islamic Azad University in Abadan when he was arrested in October 2008. Inspired by his two teachers, who at that time were still free, “I was campaigning about human rights and raising awareness of Ahwazi culture,” he said.

He was accused of threatening national security and, over four months in 2008, subjected to repeated abuse and torture, at first in solitary confinement before being transferred to the infamous Sepidar prison in Ahvaz.

Eventually, he was brought before a court in Ramshir, where a lawyer hired by his family successfully appealed to the judge to release him on bail, pending trial.

The threat of a trial hung over him, but Hamid was determined to complete his university studies and graduated in 2011. But that same year his two teachers were arrested and Hamid decided to flee the country.

“I smuggled myself across the border to Turkey,” he said. “I had friends waiting for me in Ankara and there I introduced myself to the representative of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.”

Hamid was granted refugee status and given the chance of a new start in the US. Since 2015 he has lived in Charlottesville, Virginia, with his wife, who was able to join him in the US, and their two young daughters, both born in their adoptive country.

In the US, Hamid has built a new life, working as an activist and freelance journalist, and has written hundreds of articles about the plight of the Ahwazi for a wide range of international media.

“I came to the US to get out of Iran, to survive,” he said, “but also to be a voice, to be an ambassador for the cause of my people.”

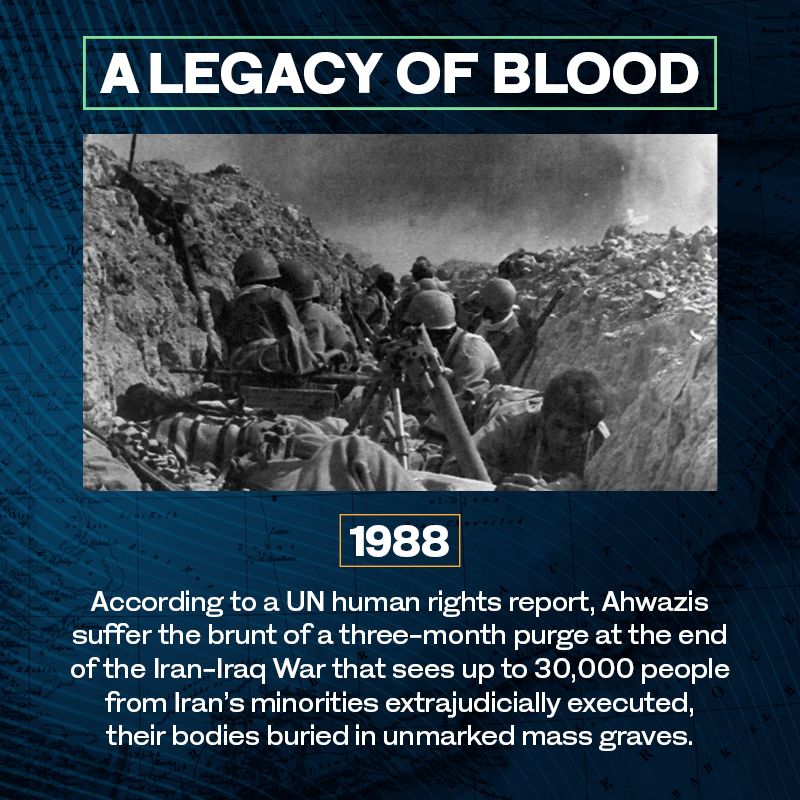

Rahim Hamid’s people, the Ahwazi, bear the brunt of the arbitrary arrests, torture, disappearances and extrajudicial executions experienced by all of Iran’s non-Persian minority communities. According to a UN human rights report in September 2020, an extraordinary mass purge of supposed dissidents carried out at the end of the Iran-Iraq war in 1988 was felt most heavily by the Ahwazi population of Khuzestan.

Between July and September 1988 “Iranian authorities forcibly disappeared and extrajudicially executed thousands of imprisoned political dissidents affiliated with political opposition groups in 32 cities in secret, and discarded their bodies, mostly in unmarked mass graves.”

Some estimates put the number killed as high as 30,000.

Targeted ostensibly at those who had supposedly collaborated with Iraq, the purge extended to a broad range of dissidents. The killings took place in cities across Iran, but “in particular in Ahvaz (and) Dezful in Khuzestan province.”

The horror of these events, in which eyewitnesses told of prisoners being hanged from cranes in batches of six at half-hourly intervals, lives on for the families of the disappeared, for whom there is still no closure.

Iran continues to disappear members of its minority communities, including the Ahwazi. According to the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, between 1980 and August 2021 there were 548 reported cases of disappearance in Iran, with 103 of the victims women. These are only the documented cases. The true number is believed to be much higher.

Yousef Silavi, pictured with his wife Tajamolok, left, and daughter Mona before his disappearance in 2009. His fate remains uncertain.

Yousef Silavi, pictured with his wife Tajamolok, left, and daughter Mona before his disappearance in 2009. His fate remains uncertain.

One of those missing is Yousef Silavi, a retired technician from Iran’s Ahwazi minority, who was last seen alive in his home in Ahvaz on or about Nov. 6, 2009. His family believe he was abducted. Three years ago they heard unofficially that he was alive and being held in an Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps prison. They have heard nothing since, but live in hope.

Without doubt the persecution of Iran’s Arabs owes much to institutionalized racism, and to a fearful awareness in Tehran that half the country it likes to pretend is a single, united Persian entity is, in fact, composed of ethnic minorities which, it reasons, must be controlled by suppression.

For centuries, however, the Arabs of Arabistan enjoyed a peaceful autonomy, technically part of the Persian sphere of influence, but in reality left to their own devices, free to follow their own leaders, laws and customs.

The moment all that began to change can be traced to within an hour on a single day in May over a century ago.

From autonomy to betrayal

At about 4 a.m. on May 26, 1908, George Reynolds was woken in his camp in Masjid-i-Suleiman, in the rugged foothills of the Zagros Mountains, by the overwhelming smell of sulfur.

Reynolds, an experienced British engineer and geologist working for a syndicate in London, knew exactly what it meant. After six long and frustrating years spent prospecting in vain in the northwest of Persia, he had finally struck oil.

Oil gushes from one of the first wells to be drilled in Masjid-i-Suleiman in Iran in 1908. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Oil gushes from one of the first wells to be drilled in Masjid-i-Suleiman in Iran in 1908. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Life for the Arabs of Arabistan, on whose land the historic find had been made, would never be the same again.

In December 1902, at about the same time that Reynolds had begun his search, Judge Jerome Saldanha of the Bombay Provincial Civil Service completed his top-secret “Precis of Persian Arabistan Affairs” for the foreign department of the British Government of India.

Here, he wrote, was “the ancient Elam, the garden of the world” — an allusion to the pre-Iranian Elamite civilization that had ruled an area roughly equivalent to the modern-day Iranian province of Khuzestan.

The Elamites were responsible for the construction in about 1250 B.C. of Choga Zambil, a palace and temple complex within the ancient city of Dur Untash, which includes one of the best surviving examples of the ziggurat, the distinctive stepped pyramidal monuments built mainly in ancient Mesopotamia.

Choga Zambil, one of the few ziggurats outside Mesopotamia, in the ancient Elamite city of Dur Untash, 80km north of Ahvaz. (Getty Images)

This city, which in 1979 was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site, gives its name to the Canadian-based Dur Untash Studies Center, set up by Ahwazis in exile “to provide credible and informative analysis, research, studies and other information resources on the Ahwazi cause.”

Choga Zambil is about 70 km west of where the Middle East’s first historic oil find would be made.

For Saldanha, writing in 1902, it was “curious that this magnificently fertile region was until recently closed to the commerce of the world,” a state of affairs for which he blamed “the jealousy of the Persians.”

Although the Karun river had recently been opened up to British commerce by the sheikhs of Arabistan, Persian antipathy remained an obstacle to revitalizing the agricultural potential of the region. “Many a scheme has been put forward to restore its ancient irrigation works or to start new ones,” wrote Saldanha, “only to be shelved in the archives of Tehran.”

Various tribes competed for authority in Arabistan, but by the 19th century power had passed to the Muhaysin, who controlled the port town of Mohammerah, situated strategically near the head of the Gulf at the junction of the Karun and the Shatt Al-Arab.

It was Sheikh Jabir of the Muhaysin, who ruled from 1819 to 1881, “operating Mohammerah as a free port and exhibiting commercial tendencies,” who first “attracted the favorable attentions of the British,” wrote American historian William Theodore Strunk in 1977.

A British military report, written in 1924, recalled Sheikh Jabir as “an able and exceptionally long-lived chief” who had “aided the British government in its efforts to suppress piracy on the river (Karun) and incurred the suspicion of his Persian Suzerain, who was inclined to listen to the rumor that the sheikh intended to throw off his allegiance and transfer his principality to the British.”

The semi-independent status of Arabistan, and its historical and geographical affiliation to Mesopotamia rather than Persia, had been dealt a blow in 1848 with the Treaty of Erzerum, under which Turkey and Persia resolved longstanding border disputes. Turkey agreed to recognize “the full sovereign rights of the Persian government” to the town and port of Mohammerah, the island of Khidhr (Abadan) and the rest of Arabistan.

Britain’s commercial interests, however, kept Persian interference in Arabistan’s affairs to a minimum, and when war broke out between Britain and Persia in 1856 over Tehran’s ambitions in Afghanistan, Sheikh Jabir sided with the British. British troops attacked Persian forces in Mohammerah and “the Persian army fled precipitately — not less than 300 of their number were killed, and in addition large numbers were killed by Arabs.”

The British assault on Bushire by the 20th Bombay Native Infantry during the Anglo-Persian War of 1856-1857. (Getty Images)

The British assault on Bushire by the 20th Bombay Native Infantry during the Anglo-Persian War of 1856-1857. (Getty Images)

In the hope of shrugging off the Persian yoke, the Arabs of Arabistan had nailed their colors firmly to the British mast. But for all the promises and assurances that would be offered by the British over the coming years, ultimately their dream of independence would be betrayed.

In 1881, Sheikh Jabir was succeeded by his son, Mizil Khan, who in 1888 opened the Karun river to British commercial interests and allowed the British to establish a vice-consulate at Mohammerah.

Before his assassination in 1897, Mizil Khan of Mohammerah forged close relations with the British, which were built upon by his successor, his brother Sheikh Khazaal.

Before his assassination in 1897, Mizil Khan of Mohammerah forged close relations with the British, which were built upon by his successor, his brother Sheikh Khazaal.

“Thenceforth,” as the British military report of 1924 recorded, “the affairs for Arabistan began to assume more than academic importance to British diplomatic and political authorities.”

On June 2, 1897, Sheikh Mizil was assassinated as he arrived by boat at his waterside palace of Fallahiyah at Mohammerah. He was succeeded by his brother, Khazaal.

By now, imperial Britain was heavily invested in Arabistan, which it regarded as a buffer state in service to its overriding objective of protecting India against all-comers, which at the time meant Russia, Turkey and Germany.

As a British Foreign Office summary of dealings with Sheikh Khazaal published in 1946 put it, “an essential part of British policy in the Gulf was the establishment of good relations and the conclusion of treaties with the various Arab rulers, and the sheikhs of Mohammerah, controlling territory at the head of the Gulf, thus came very prominently into the general scheme.”

Although considered by the British to be “nominally Persian subjects, they enjoyed in Arabistan a large measure of autonomy and semi-independence.”

Sheikh Khazaal set about trying to strengthen his position with Tehran in a series of negotiations in which the British brought pressure to bear behind the scenes on his behalf. The result was a historic concession made in 1903 by Muzaffar Al-Din, the Shah of Persia, who granted the sheikh a firman, or formal decree, “which recognized as ‘perpetual properties’ the lands of the sheikh and his tribes.”

Muzaffar Al-Din, the Shah of Persia, who in 1903 formally recognized that Arabistan belonged to Sheikh Khazaal and his people in perpetuity. (Getty Images)

Ahwazi activists insist that this document alone means that the later Persian occupation of Arabistan in 1925 can be seen only as an illegal act under international law. The decree stipulated that the Persian government “should have no right to take possession of, or interfere with, the properties.”

In the years following the 1903 agreement, Sheikh Khazaal “suffered little serious interference from the central government, which appears to have been content to allow the sheikh to rule undisturbed over his territories.”

But then came the discovery of oil.

In 1901, for a fee of £20,000 (about £2 million today), Persia had awarded a 60-year concession to explore for oil to a British businessman, William Knox D’Arcy. The concession covered three-quarters of Persia, including the territories of Sheikh Khazaal.

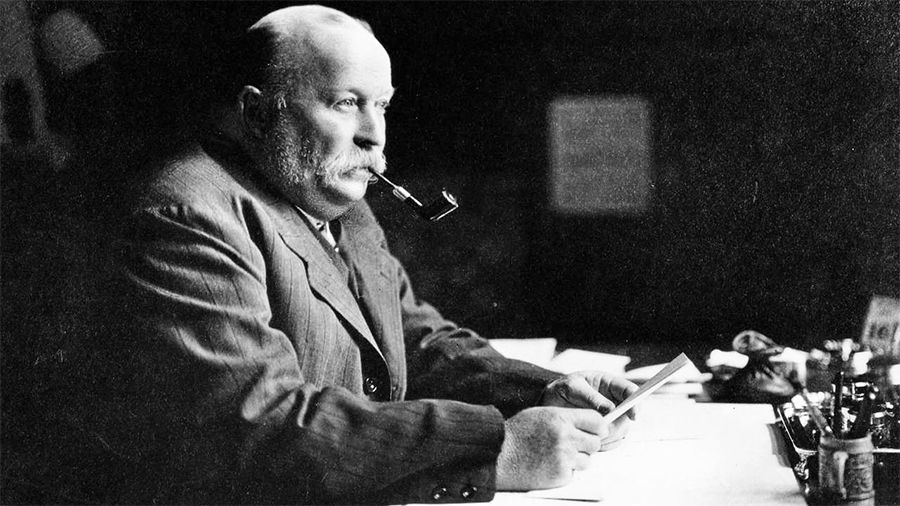

William Knox D’Arcy, who in 1901 began the search for oil that would transform the Middle East – and the fortunes of the Arabs of Persia.

William Knox D’Arcy, who in 1901 began the search for oil that would transform the Middle East – and the fortunes of the Arabs of Persia.

After several years, no significant oil deposits had been found, and in 1907 D’Arcy sold out to a syndicate, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company — the forerunner of BP.

The following year, the syndicate’s major backers decided to cut their losses. But on May 26, 1908, even as a letter was on its way instructing its team in Persia to give up and return home, oil was finally struck in Arabistan, at Masjid-i-Sulaiman.

Encouraged, on July 16, 1909, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company paid Sheikh Khazaal £10,000 to lease further sites on Abadan Island and elsewhere in his territory. By the terms of the firman issued by the shah just five years earlier, the sheikh was fully entitled to strike the deal.

Britain continued to support the sheikh whenever possible — or, at least, when it suited its interests. In 1910, the British stepped in and defused a minor dispute with Turkey along the Shatt Al-Arab. It was, noted the Foreign Office, “deemed desirable to counteract a certain amount of loss of prestige suffered by the sheikh and also to make a demonstration in face of the growth of Turkish ambitions in the Arabian Gulf area.”

Accordingly, the political resident sailed to Mohammerah in a warship and, in a ceremony at the sheikh’s palace at Fallahiyah on Oct. 15, 1910, presented him with the insignia and title of a Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire.

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Britain’s interest in Arabistan was suddenly focused less on Persian interference in its affairs than on the more immediate menace from Germany and Turkey. It was, as a later British Foreign Office review noted, “regarded as clearly essential that we should reaffirm and strengthen our assurances to the sheikh.”

For his part, throughout the war, the sheikh stood firmly by British interests. Toward the end of 1915, when the British feared Persia was poised to enter the war on Germany’s side, there was even “some discussion of recognizing the sheikh’s independence in that event.”

Had Arabistan been recognized then as an independent nation, backed by the might of the British empire, the Middle East today might look very different indeed.

But after the First World War a dramatic shift in British priorities sealed the fate of Sheikh Khazaal, and signaled the end of the prospect of Arabistan as an independent entity.

Following the Russian revolution in 1917, it became increasingly clear that the Bolsheviks had designs on Persia. In 1921, Britain, fearing that the failing Persian Qajar dynasty might side with the Russians, conspired with Reza Khan, leader of Persia’s Cossack Brigade, to stage a coup.

Reza Khan, Shah of Persia. With Britain's backing, he reneged on his predecessor's pledge in order to seize Arabistan's oil. (Getty Images)

It was a fateful alliance. Reza Khan, as a secret British report in 1946 would later conclude, “was ultimately personally responsible for the sheikh’s complete downfall.”

Reza Khan was determined to bring the whole of Persia under central control and, in 1922, he sent troops into Arabistan.

As US historian Chelsi Mueller wrote in her 2020 book “The Origins of the Arab-Iranian Conflict,” Reza Khan “eyed Arabistan not only because it was the only remaining province that had not yet been penetrated by the authority of central government but also because he had come to appreciate the potential of Arabistan’s oil industry to provide much-needed revenues.”

Sheikh Khazaal, invoking previous promises he had been given, asked for Britain’s protection. Instead, he was brushed off, and urged to “fulfill his obligations to the Persian government.”

Britain, now fully behind the regime of Reza Khan, was in the process of abandoning Sheikh Khazaal and sacrificing Arabistan to its own geopolitical needs.

In a despatch sent on Sept. 4, 1922, Sir Percy Loraine, the British envoy to Iran, wrote that in Persia “it would be preferable to deal with a strong central authority,” which “would involve a loosening of our relations with local rulers.”

Over the next couple of years there followed a series of three-way political maneuvers between Reza Khan, Britain and the sheikh of Mohammerah, throughout which the Persian government, despite constant assurances to the contrary, gradually increased its interference in the day-to-day affairs of Arabistan.

Matters came to a head in August 1924, when the Persian government informed Sheikh Khazaal that the firman granted him by Shah Muzaffar Al-Din in 1903 was no longer valid.

Coveted by the Persian government, the oil that should have been the making of Arabistan was to be its undoing.

The sheikh told the British that he had had enough and planned to fight, but if he hoped that would force them to side with him, he was disappointed. Britain’s vice-consul at Ahwaz warned him that if he were “to commit any rebellious act” against their Persian protege, “he would be putting himself in the wrong and would prejudice his case with His Majesty’s Government.”

Regardless, Sheikh Khazaal demanded that Reza Khan withdraw all troops from Arabistan and reconfirm the legality of the 1903 firman. After a few weeks of shuttle diplomacy, the British were pleasantly surprised when, in September 1924, Reza Khan appeared to back down completely.

But there was an ominous catch. In return, the sheikh had to leave Persia for three months and, on his return, make “a suitable declaration of submission” to the authority of Tehran.

It was, concluded the British, “clear that the old regime had come to an end and that Reza Khan, having established a stranglehold over Khuzestan, would be unlikely ever voluntarily to relinquish it.”

The British government was “now in an embarrassing position. The services which the sheikh had rendered them in the past made it undesirable that they should abruptly terminate their assurances to the sheikh.”

On the other hand, Britain had now decided to support the government in Tehran and could ill afford to present the Soviets “with wonderful opportunities for fishing in troubled waters.”

For his part, the British noted, “the sheikh appears to have resigned himself to the new regime” and had informed Reza Khan that “he wished to divide his properties among his sons and travel abroad.”

But on April 18, 1925, Sheikh Khazaal and his son, Abdul Hamid, were arrested on Reza Khan’s orders and taken to Tehran. Ahwazi activists date the occupation of Al-Ahwaz by the Iranian state to April 20, 1925.

Held under virtual house arrest, the sheikh would spend the remaining 11 years of his life in futile negotiations with Tehran. These were marked, noted the British, by a series of “gross breaches of faith on the part of the central government, who had obviously no intention of carrying out the promises given to the sheikh.”

The Persians, the British concluded, “were obviously merely waiting for the sheikh to die,” a wish that was finally granted during the night of May 24, 1936.

Five years later, the wheel of fortune turned again, but not to the benefit of the Ahwazi.

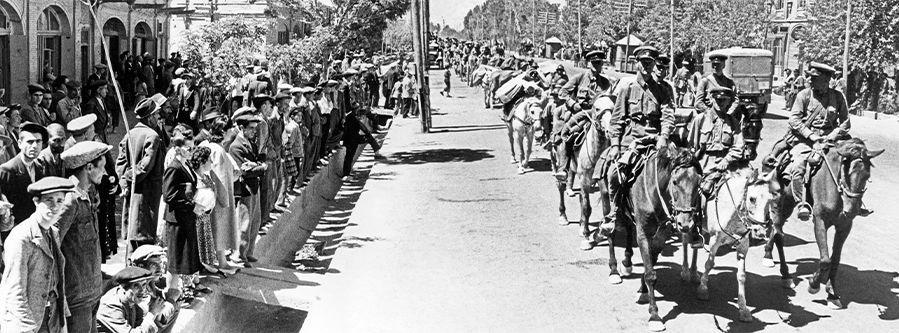

Red Army troops enter Tabriz during the Anglo-Soviet Invasion of Iran in the Second World War, which saw Britain turn its back on Persia's Arabs. (TASS/Getty Images)

Red Army troops enter Tabriz during the Anglo-Soviet Invasion of Iran in the Second World War, which saw Britain turn its back on Persia's Arabs. (TASS/Getty Images)

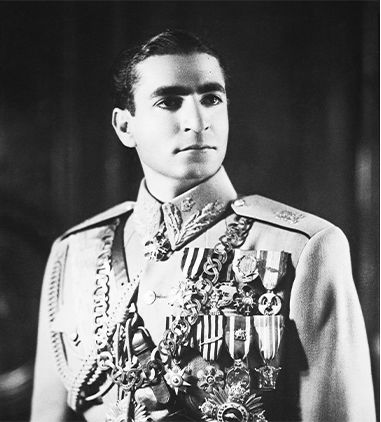

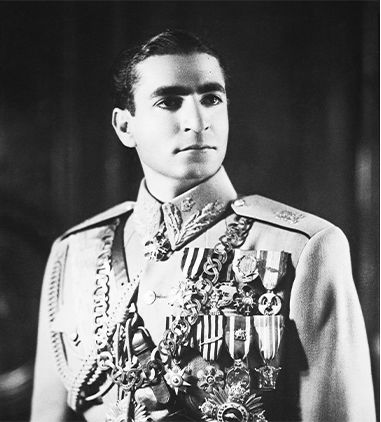

In August 1941, Britain and the Soviet Union, by now allies in the Second World War, invaded Persia to seize the all-important oil fields and force the abdication of the now pro-Nazi Reza Khan. He stepped down on Sept. 16, 1941, to be replaced by his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who as the last Shah of Iran would be toppled by the Islamic revolution in 1979.

The persecution of Iran's Arabs and other minorities continued under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who succeeded his father in 1941, and after his overthrow by the Iranian Revolution in 1979. (Getty Images)

The appearance of British troops, sweeping into Arabistan from Iraq, raised fresh hope among the Ahwazi that independence might once again be within their grasp. It was a forlorn hope, however.

On Sept. 7, 1941 the commander of the British 8th Indian Division in Persia wrote to his headquarters in Baghdad to report that Sheikh Chassib, the eldest son of the late Sheikh Khazaal, living in exile in Iraq, was “endeavoring to stir up the tribes in the south with a view to restoring the past position of the family.”

He added: “The last thing we require right now in Khuzestan is a renewal of the matter.”

Accordingly, Sheikh Chassib was ordered to desist. Britain had washed its hands of Arabistan for once and for all. From now on, persecution at the hands of the Persian government in Tehran would be the lot of the Ahwazi.

Choga Zambil, one of the few ziggurats outside Mesopotamia, in the ancient Elamite city of Dur Untash, 80km north of Ahvaz. (Getty Images)

Choga Zambil, one of the few ziggurats outside Mesopotamia, in the ancient Elamite city of Dur Untash, 80km north of Ahvaz. (Getty Images)

Muzaffar Al-Din, the Shah of Persia, who in 1903 formally recognized that Arabistan belonged to Sheikh Khazaal and his people in perpetuity. (Getty Images)

Muzaffar Al-Din, the Shah of Persia, who in 1903 formally recognized that Arabistan belonged to Sheikh Khazaal and his people in perpetuity. (Getty Images)

Reza Khan, Shah of Persia. With Britain's backing, he reneged on his predecessor's pledge in order to seize Arabistan's oil. (Getty Images)

Reza Khan, Shah of Persia. With Britain's backing, he reneged on his predecessor's pledge in order to seize Arabistan's oil. (Getty Images)

The persecution of Iran's Arabs and other minorities continued under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who succeeded his father in 1941, and after his overthrow by the Iranian Revolution in 1979. (Getty Images)

The persecution of Iran's Arabs and other minorities continued under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who succeeded his father in 1941, and after his overthrow by the Iranian Revolution in 1979. (Getty Images)

A persecuted people

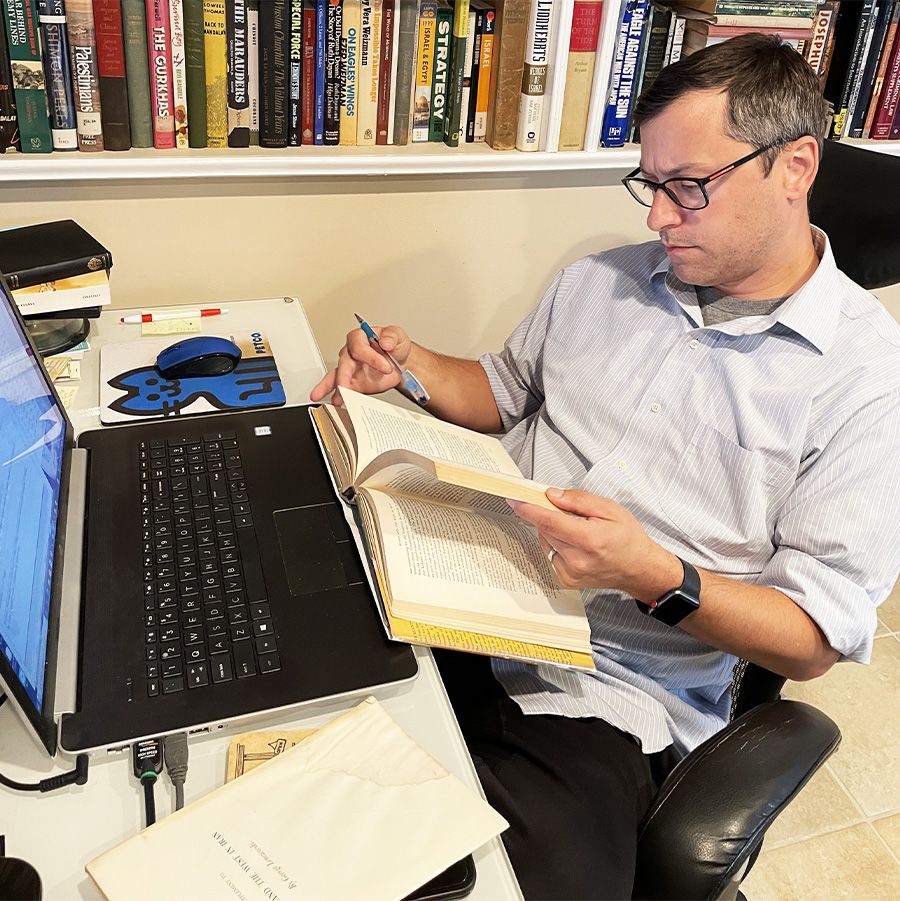

US attorney and historian Aaron Meyer, an expert in international law, and a member of the Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa who has written extensively about the Ahwazi, became aware of their plight only within the past two years, following a chance encounter with a member of the diaspora living in the US.

US lawyer Aaron Meyer, "horrified" after stumbling upon the plight of the Ahwazi. (Ilyana Meyer)

US lawyer Aaron Meyer, "horrified" after stumbling upon the plight of the Ahwazi. (Ilyana Meyer)

“The more I looked into it, the more horrified I was by what’s been happening, particularly over the past 40 years but also for roughly a century,” he said.

He remains shocked by how few people in the West know anything about the Ahwazi.

“I’m pretty familiar with most of the minority groups throughout the Middle East, yet I, too, had no idea. This is a story about human rights that should be very much in the popular consciousness, but it’s not.”

One reason, Meyer believes, is that “Iran has been very successful at projecting an image of a homogeneous Persian-Iranian civilization that does not actually exist. Less than half the population is ethnically Persian.”

The history of imperial adventures in the region has also left its mark.

“The Ahwazis were pawns,” he said. “In the early 20th century, you had Britain and Russia jockeying for position over oil and it was in everyone’s interest to pretend that the Ahwazi just didn’t exist.”

The UN, said Meyer, “has completely and utterly failed the Ahwazi. There is a special rapporteur, who occasionally will mention them in the context of general Iranian suppression and human rights violations, but when you’re dealing with thousands of human rights violations, one line about the plight of the Ahwazi doesn’t really go very far. They mention it, but there is no accountability.”

In reality, there is little the UN can do beyond urging Iran to change its ways — formal pleas that invariably go unanswered. Besides, the plight of the Ahwazi is just one of many human rights issues that confront Javaid Rehman, a professor of law at Brunel University, London, who since 2018 has been the UN’s special rapporteur on human rights in Iran.

Delivering his fourth annual report to the UN General Assembly on Oct. 25, 2021, Rehman spoke of the “extensive, vague and arbitrary grounds in Iran for imposing the death sentence, which quickly can turn this punishment into a political tool.”

But in the annual report there was no direct mention of the plight of the Ahwazi, or of the extrajudicial killings of Arabs in Khuzestan that had occurred throughout the first part of the year.

“Such killings are committed in almost every month of the year,” the Dur Untash Studies Center (DUSC) reported in March 2021, in a paper highlighting an Iranian “shoot to kill” policy that had seen at least a dozen young Ahwazi men killed at checkpoints between June 2019 and May 2021. The youngest victim was 17-year-old Ali Rashedi, shot in the head and back on Sept. 4, 2019 while riding his moped through an unmarked checkpoint.

Ali Rashedi, 17, one of many Ahwazi men shot dead at Iranian checkpoints in what activists say is a shoot-to-kill policy.

Ali Rashedi, 17, one of many Ahwazi men shot dead at Iranian checkpoints in what activists say is a shoot-to-kill policy.

In addition to executions, random arrests and shootings, the Ahwazi say Tehran has been pursuing a strategy of oppressing Iranian Arabs by destroying the very environment in which they live.

A series of dams has been constructed on the region’s four key rivers, including the Karun, partly to divert water to ethnically Persian areas of the country. For years this policy, as a paper published by DUSC in 2020 reported, has “wreaked environmental havoc, leading to widespread desertification and a massive reduction in the cultivable areas in Ahwaz.”

Even the head of Iran’s Environmental Protection Agency has reportedly admitted that the huge Gotvand dam on the Karun, completed in 2012, is responsible for droughts in Khuzestan, and for the increasing salinity of the water and soil in the province.

The vast Gotvand dam on the Karun River, which experts say has helped to create an ecological catastrophe downstream in Al-Ahwaz.

The vast Gotvand dam on the Karun River, which experts say has helped to create an ecological catastrophe downstream in Al-Ahwaz.

“With this one engineering mistake, we turned Khuzestan’s water salty,” IranWire quoted Isa Kalantari saying during an address to students at Amir Kabir University in July 2018. According to the report, studies carried out by Tehran University found that the dam had increased the salt content in the Karun river by 35 percent.

In 2020, exiled Ahwazi activist Rahim Hamid and Aaron Meyer collaborated on a paper for DUSC with the uncompromising title “Iran’s Systematic Environmental Destruction is Genocide Against the Ahwazi People.” The regime’s policies, they argued, had “destroyed the environment in Ahwaz in a deliberate and systematic way.”

The once-fertile and bountiful farmland of Ahwaz had been transformed into “arid wastelands and desert dotted with oil and gas refineries, with the lack of plant life increasing the intensity and regularity of sandstorms that now regularly blanket the region’s cities in choking, gritty, heavily polluted dust.”

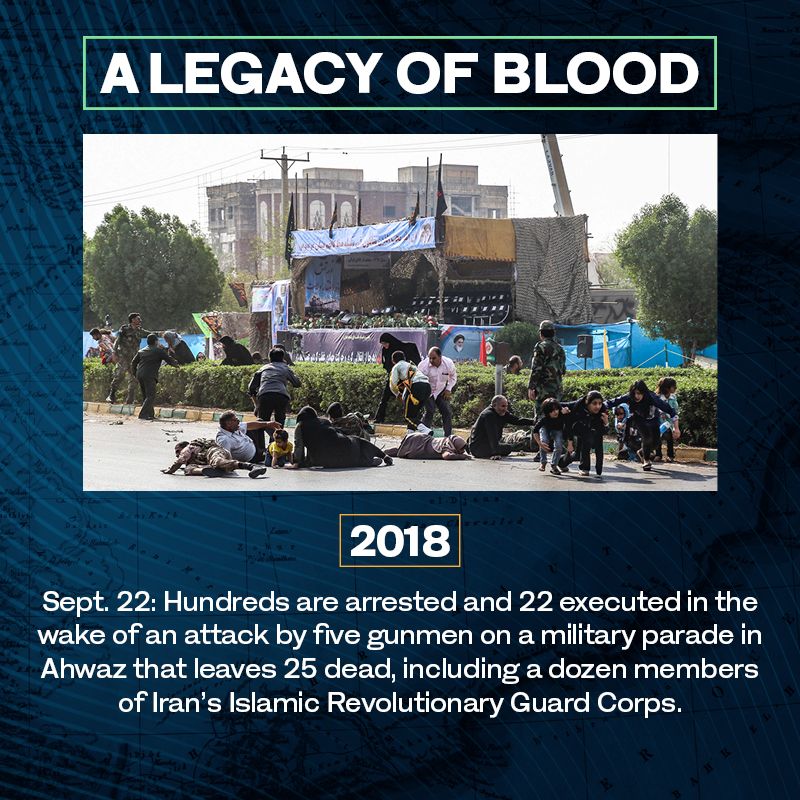

Inevitably, frustration among the Ahwazi at such transparent injustice has boiled over into protests, which have been met with the customary violent response of the Iranian state.

In July 2021, tensions over water shortages flared into demonstrations in several cities across Khuzestan province, where summer temperatures can reach 50 degrees Celsius. Amnesty International said it had confirmed that at least eight people, including a teenage boy, had been shot and killed by the authorities during the protests.

Hamid and Meyer have argued powerfully that Iran’s systematic assault on the Ahwazi people amounts to genocide, as defined by the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, to which Iran became a signatory on Aug. 14, 1956.

In the convention the UN pledged to punish those who committed genocide, but in the case of Iran has done no such thing.

“Just because it is not possible to prosecute the Iranian government collectively or individually on a domestic level does not mean that there is no capacity to sue the perpetrators of this genocide,” wrote Hamid and Meyer.

“It is possible to hold the relevant Iranian individuals and government officials accountable before the international judiciary should they travel abroad.”

In reality, however, the Ahwazi are on their own, as they have been ever since 1925.

Hopes and dreams

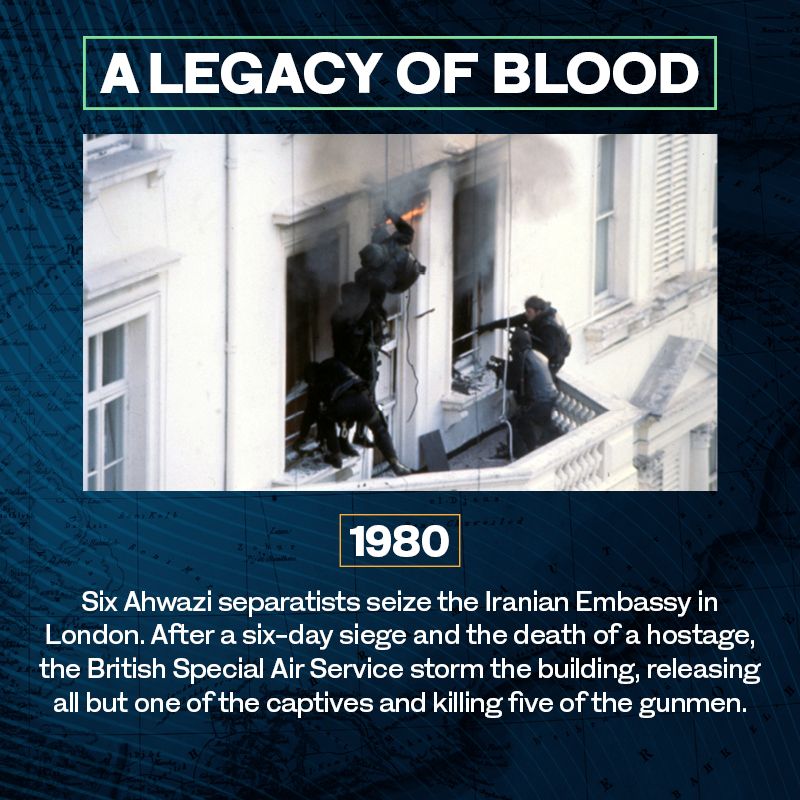

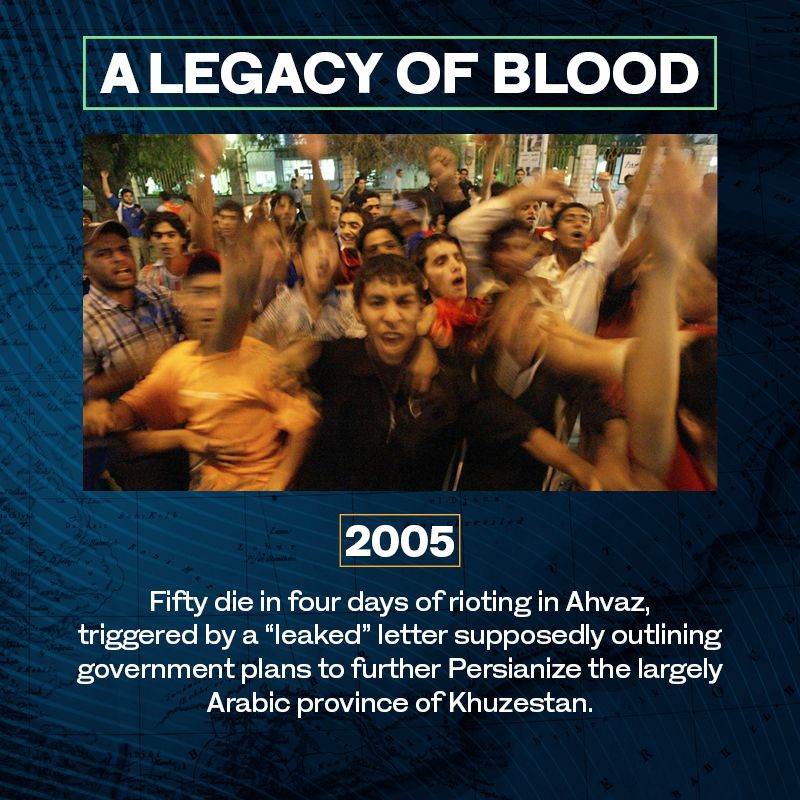

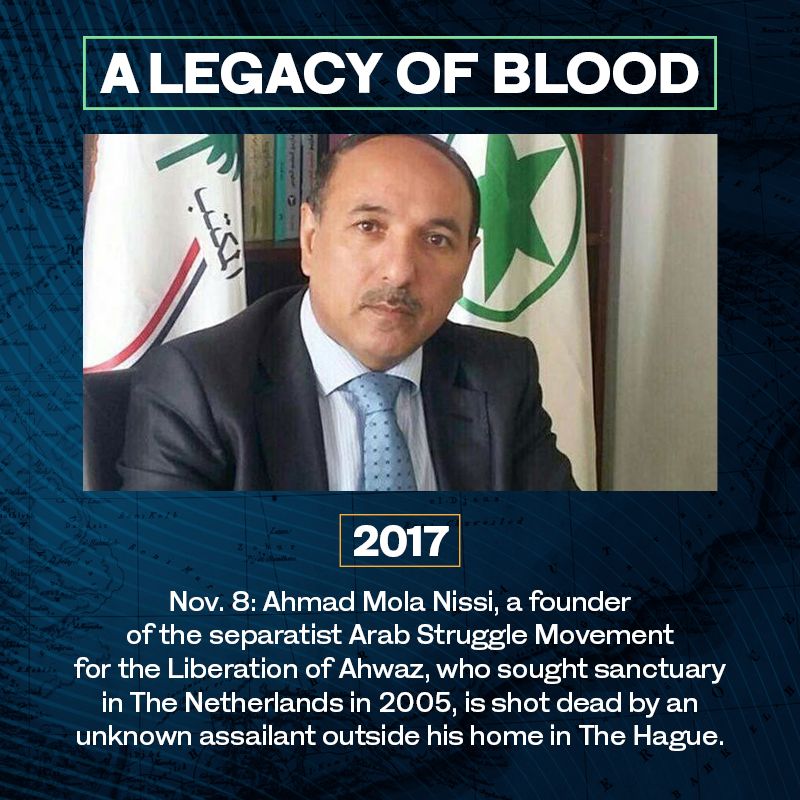

On April 15, 2005, four days of deadly riots broke out in the city of Ahvaz. The trigger was the apparent leak of a letter, supposedly written by an Iranian presidential adviser, that seemed to confirm Ahwazi fears that the government was intent on further Persianizing the province of Khuzestan.

The authenticity of the letter remains uncertain. The result, however, was all too clear. As many as 50 people were killed in the subsequent protests, while dozens more were wounded and hundreds arrested.

Two months after the riots, Karim Abdian, director of Virginia-based NGO the Ahwaz Education and Human Rights Foundation, addressed the minorities working group of the UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights.

Karim Abdian, director of the Ahwaz Education and Human Rights Foundation, says the Ahwazi have been subjected to “political, cultural, social and economic subjugation."

The Ahwazi, he said, have been subjected to “political, cultural, social and economic subjugation, and treated as second and third-class citizens,” by the Iranian monarchy in the past and by the current clerical regime. Nevertheless, they still have “faith in the international community’s ability to present a just and viable solution to resolve this conflict peacefully.”

The inequities suffered by his people included the imposition in Iran of a single-language education system in a society in which two-thirds of the population were non-Persian speakers. This had “a devastating effect on non-dominant minorities,” leading to “economic deprivation, political sidelining and negation of cultural identity.”

In Iran, he said, up to 80 percent of Persian pupils graduate from high school. The rate for Arabs in the country was about 25 percent.

Protests, or even the suspicion of political or social activism, had led to the incarceration of thousands of Ahwazi political prisoners.

Sixteen years after he made his powerful plea for help to the UN group, Abdian despairs of seeing an improvement in the position of his people in Iran.

“I don’t see any way out,” he said.

“As an Ahwazi Arab you cannot even give your child an Arabic name, it has to be either Persian or the name of one of the Shiite imams. So, this nation, which owns the land that currently produces 80 percent of the oil, 65 percent of the gas and 35 percent of the water of Iran, lives in abject poverty.”

Ahwazi Arabs “have faced this dilemma for the past 100 years. They were dealt the worst hand in history.”

Real progress, he said, remains elusive, and the Ahwazi are divided over how to achieve it.

“Within our movement there are those who say that we need to push for independence from Iran, but I am of the belief that is absolutely impossible,” said Abdian. “I know that the UN, the US, Europe and organizations such as the World Bank and the IMF won’t go for it.”

He added: “The role of politics is to seek what’s feasible, what’s doable, what’s executable. There is nothing wrong with wanting independence, but is it doable? And if not, let’s put our efforts into something that is.”

However, Mousa Sharififarid, a senior journalist and political analyst at the Dubai-based Al-Arabiya news channel, said that some Ahwazi “believe that we could be an independent state, like other Arab countries, such as Kuwait, the Emirates, Iraq.”

Journalist and analyst Mousa Sharififarid says many Ahwazi believe federalism offers the best hope for them and all of Iran's oppressed minorities.

Journalist and analyst Mousa Sharififarid says many Ahwazi believe federalism offers the best hope for them and all of Iran's oppressed minorities.

He said: “They argue that the Ahwazi people are closer, culturally and geographically, to the Arab world than to the Persian. After all, it is about 700 km from the city of Ahvaz to Tehran, but only the Shatt Al-Arab separates Ahvaz from Iraq, and only the Gulf lies between Ahvaz and the other Arab Gulf countries.”

But for other Ahwazi, the failed attempt in 2017 by the Kurdistan region of Iraq to gain independence serves as a warning, according to Sharififarid. In September that year the Kurdish regional government staged an unofficial referendum, unapproved by Baghdad.

For those Ahwazi hoping to secede from Iran, the failure of Iraq's Kurds to win independence in 2017 serves as a cautionary tale. (Safin Hamed/AFP)

Although more than 92 percent voted for independence from Iraq, few countries in the region and beyond supported the move. Iran was particularly belligerent in its opposition to the vote, which resulted in the loss of disputed territories to Iraq, the resignation of Kurdish president Masoud Barzani, and the death of the dream of independence.

Many of those doubtful about the potential for independence, added Sharififarid, believe that federalism is the best way to secure the rights of the Ahwazi people and Iran’s many other ethnic minorities. Ethnic Persians account for only about 55 percent of Iran’s population.

“They could have their own parliament in the region within Iran and their own language, and they could share some of the assets of their region, such as the oil and gas, which currently do not benefit the Ahwazi economy,” he said.

For Abdian, the Ahwazis’ only hope lies in regime change and the transformation of Iran into a federalist state with semi-autonomous regions.

“It is very much a right of the people to have a decent government, not a government that kills and oppresses them,” he said. “Therefore, we advocate the nonviolent overthrow of this government and the establishment of a federal republic of Iran, under which the Arabs will have their own state or province and can exercise self-determination.”

Pressure is building in Iran among the country’s minority ethnic groups, he said, because Persian nationalists “refuse to acknowledge the fact that Iran is made up of all these different nationalities, and insist the country belongs only to them. Just because at one point in history British imperialists decided to put the Persians in power doesn’t mean that they should be in power now.”

Ahwazi writer and journalist Yousef Azizi, who fled Iran for London in 2009, is not without hope for his people.

Modern Ahwazis, he said, have access to Arabic-language television stations, a window on the world that has allowed them to follow global developments, such as the Arab spring, that is denied to Farsi-speaking Iranians.

“This gives our people a potential that the Persians haven’t got,” he said.

The regime, he knows, “maybe will not topple in two days, two months or two years. But the struggle is like climbing stairs — you go up, step by step.

“I don’t believe it is a bleak picture. I think the process of struggling will be fruitful. And, besides, if we don’t struggle, we do not get anything.”

The struggle is not helped, he said, by the fact that the world seems to have forgotten about the Ahwazi.

In September 2019, the Washington Institute for Near East Policy reported that “extrajudicial killings of Ahwazi Arabs, both activists and non-activists,” were carried out with impunity, thanks in part to the general indifference of the rest of the world.

It added: “There are 10 million Ahwazis in Iran who are perpetual targets of a vicious bigoted regime, and this will remain the case unless the international community chooses to pressure Iran to stop this targeting.”

Azizi said that the Ahwazi elite must do more to raise the profile of their people and highlight their suffering.

“What the Palestinians experienced in 1948, we experienced in 1925,” he said, “but the Palestinian cause is far more widely known in the world than the Ahwazi. That must change.”

Karim Abdian, director of the Ahwaz Education and Human Rights Foundation, says the Ahwazi have been subjected to “political, cultural, social and economic subjugation."

Karim Abdian, director of the Ahwaz Education and Human Rights Foundation, says the Ahwazi have been subjected to “political, cultural, social and economic subjugation."

For those Ahwazi hoping to secede from Iran, the failure of Iraq's Kurds to win independence in 2017 serves as a cautionary tale. (Safin Hamed/AFP)

For those Ahwazi hoping to secede from Iran, the failure of Iraq's Kurds to win independence in 2017 serves as a cautionary tale. (Safin Hamed/AFP)

Credits

Writing and research: Jonathan Gornall, Maedeh Sharifi

Editor: Tarek Ali Ahmad

Creative director: Simon Khalil

Designer: Omar Nashashibi

Graphics: Waleed Rabin

Video producer: Mohammed Qenan

Video editor: Ali Noori

Picture researcher: Sheila Mayo

Copy editor: Les Webb

French editor: Zeina Zbibo

Social media: Jad Bitar, Daniel Fountain

Producer: Arkan Aladnani

Editor-in-Chief: Faisal J. Abbas