LONDON: In November 1914, Sheikh Khazaal, the last ruler of the autonomous Arab state of Arabistan, could have been forgiven for thinking the troubles of his people were over.

Oil had been discovered on his lands, promising to transform the fortunes of the Ahwazi people, and Britain stood ready to guarantee their right to autonomy. In reality, the troubles of the Ahwazi were just beginning.

Within a decade, Sheikh Khazaal was under arrest in Tehran, the name Arabistan had been wiped from the map, and the Ahwazi Arabs of Iran had fallen victim to a brutal oppression that continues to this day.

For centuries, Arab tribes had ruled a large tract of land in today’s western Iran. Al-Ahwaz, as their descendants know it today, extended north over 600 km along the east bank of the Shatt Al-Arab, and down the entire eastern littoral of the Gulf, as far south as the Strait of Hormuz.

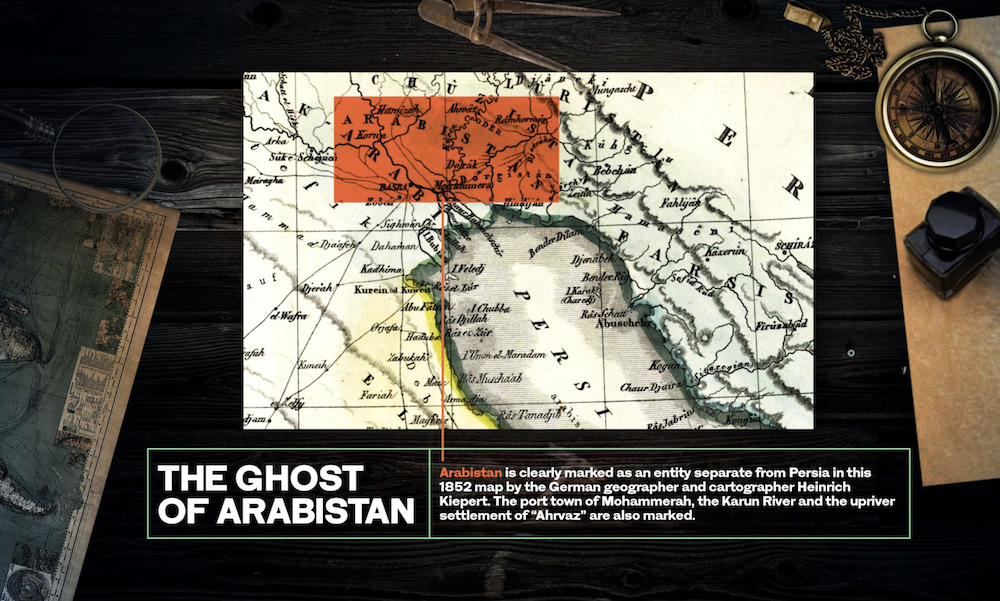

However, the independent status of Arabistan was struck a blow in 1848 by the geopolitical maneuverings of its powerful neighbors. With the Treaty of Erzurum, the Ottoman empire agreed to recognize “the full sovereign rights of the Persian government” to Arabistan. The Arab tribes whose lands were so casually signed away were not consulted.

Within 10 years, however, Sheikh Khazaal’s predecessor, Sheikh Jabir, had found a powerful friend — the British Empire.

Trade in the Gulf was vital for Britain’s interests in India and Sheikh Jabir was seen as a valuable ally, especially after his support for the British during the short Anglo-Persian war of 1856-1857 in which Britain repelled Tehran’s attempts to seize Herat in neighboring Afghanistan.

Keen to maintain Afghanistan as a buffer, the British had backed the emir of Herat’s independence. Now, it seemed, Queen Victoria’s government meant to do the same for the sheikh of Arabistan.

Read our full interactive Deep Dive on the Ahwazi Arabs and their traumatic history in Iran here

The British opened a vice-consulate at Mohammerah in 1888. By 1897, by which time Sheikh Khazaal had become the ruler of what the British referred to as the Sheikhdom of Mohammerah, imperial Britain was heavily invested in Arabistan.

As a British Foreign Office summary of dealings with Sheikh Khazaal put it, “an essential part of British policy in the Gulf was the establishment of good relations and the conclusion of treaties with the various Arab rulers, and the sheikhs of Mohammerah, controlling territory at the head of the Gulf, thus came very prominently into the general scheme.”

With the might of the British at his back, Sheikh Khazaal appeared to be steering Arabistan toward a bright, independent future.

But, in 1903, the Shah of Iran, Muzaffar Al-Din, formally recognized the lands as his in perpetuity. Then, in 1908, vast reserves of oil were found on the sheikh’s land at Masjid-i-Sulaiman.

By 1897, by which time Sheikh Khazaal (pictured) had become the ruler of what the British referred to as the Sheikhdom of Mohammerah, imperial Britain was heavily invested in Arabistan. (Supplied)

In 1910, after a minor clash between Arabistan and Ottoman forces on the Shatt Al-Arab, Britain sent a warship to Mohammerah, “to counteract a certain amount of loss of prestige suffered by the sheikh and also to make a demonstration in face of the growth of Turkish ambitions in the Arabian Gulf area.”

On board was Sir Percy Cox, the British political resident in the Gulf. In a ceremony at the Palace of Fallahiyah on Oct. 15, 1910, he presented the sheikh with reassurances of Britain’s steadfast support, and the insignia and title of a Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire.

In 1914, in a letter from Sir Percy, the sheikh had in his hand what amounted to a pledge by the greatest imperial power of the time to preserve his autonomy and protect Arabistan from the Persian government.

In the letter, dated Nov. 22, 1914, the British envoy wrote that he was now authorized “to assure your excellency personally that whatever change may take place in the form of the government of Persia, His Majesty’s government will be prepared to afford you the support necessary for obtaining a satisfactory solution, both to yourself and to us, in the event of any encroachment by the Persian government on your jurisdiction and recognized rights, or on your property in Persia.”

Read our full interactive Deep Dive on the Ahwazi Arabs and their traumatic history in Iran here

In fact, all of Britain’s assurances would prove worthless and, just 10 years later, Arabistan’s hopes of independence would be shattered.

The problem was oil. The Arabs had it, the Persians wanted it. And when it came to the crunch, the British, despite all their promises of support, chose to back the Persians.

Britain’s change of heart was triggered by the Russian revolution of 1917, after which it became clear that the Bolsheviks had designs on Persia. In 1921, fearing that the failing Persian Qajar dynasty might side with Moscow, Britain conspired with Reza Khan, the leader of Persia’s Cossack Brigade, to stage a coup.

Reza Khan, as a British report of 1946 would later concede, “was ultimately personally responsible for the sheikh’s complete downfall.”

In 1922, Reza Khan threatened to invade Arabistan, which he now regarded as the Persian province of Khuzestan. His motive, as US historian Chelsi Mueller concluded in her 2020 book “The Origins of the Arab-Iranian Conflict,” was clear.

In a ceremony at the Palace of Fallahiyah on Oct. 15, 1910, he presented the sheikh with reassurances of Britain’s steadfast support, and the insignia and title of a Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire. (Supplied)

“He eyed Arabistan not only because it was the only remaining province that had not yet been penetrated by the authority of central government but also because he had come to appreciate the potential of Arabistan’s oil industry to provide much-needed revenues,” Mueller wrote.

Sheikh Khazaal asked for Britain’s protection, invoking the many assurances he had been given. Instead, he was brushed off, and reminded of his “obligations to the Persian government.”

Time was running out for the Arabs. In a despatch sent to London on Sept. 4, 1922, Sir Percy Loraine, British envoy to Iran, wrote “it would be preferable to deal with a strong central authority rather than with a number of local rulers” in Persia. This, he added, “would involve a loosening of our relations with such local rulers.”

In August 1924, the Persian government informed Sheikh Khazaal that the pledge of autonomy he had won from Muzaffar Al-Din in 1903 was no longer valid. The sheikh appealed to the British for help, but was again rebuffed.

Reza Khan demanded the sheikh’s unconditional surrender. It was, the British concluded, “clear that the old regime had come to an end and that Reza Khan, having established a stranglehold over Khuzestan, would be unlikely ever voluntarily to relinquish it.”

Read our full interactive Deep Dive on the Ahwazi Arabs and their traumatic history in Iran here

The British government was “now in an embarrassing position” because of “the services which the sheikh had rendered them in the past.” Nevertheless, for fear of Russian incursion in Persia, Britain had now decided firmly to support the central government in Tehran.

The Ahwazi were on their own.

On April 18, 1925, Sheikh Khazaal and his son, Abdul Hamid, were arrested and taken to Tehran, where the last ruler of Arabistan would spend the remaining 11 years of his life under house arrest. The name “Arabistan” was expunged from history and the territories of the Ahwaz finally absorbed into Persian provinces.

Khazaal’s last days were spent in futile negotiations with Tehran, marked, the British noted, by a series of “gross breaches of faith on the part of the central government, which had obviously no intention of carrying out the promises given to the sheikh.”

The Persians, concluded the British, “were obviously merely waiting for the sheikh to die.” That wait ended during the night of May 24, 1936.

In the almost 100 years since the Ahwazi people lost their autonomy, they have experienced persecution and cultural oppression in almost every walk of life. Dams divert water from the Karun and other rivers for the benefit of Persian provinces of Iran, Arabic is banned in schools, while the names of towns and villages have long been Persianized. On world maps, the historic Arab port of Mohammerah became Khorramshahr.

Protests are met with violent repression. Countless citizens working to keep the flame of Arab culture alive have been arrested, disappeared, tortured, executed or gunned down at checkpoints.

Many Ahwazi who sought sanctuary overseas are working to bring the plight of the Ahwazi to the attention of the world. Even in exile, however, they are not safe.

Ahmad Mola Nissi, one of the founders of the Arab Struggle Movement for the Liberation of Ahwaz, fled Iran with his wife and children and sought asylum in the Netherlands in 2005. (Supplied)

In 2005, Ahmad Mola Nissi, one of the founders of the Arab Struggle Movement for the Liberation of Ahwaz, fled Iran with his wife and children and sought asylum in the Netherlands. On Nov. 8, 2017, he was shot dead outside his home in the Hague by an unknown assassin.

In June 2005, Karim Abdian, director of a Virginia-based NGO, the Ahwaz Education and Human Rights Foundation, appealed to the UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights.

The Ahwazi, he said, had been subjected to “political, cultural, social and economic subjugation, and are treated as second and third-class citizens,” both by the Iranian monarchy in the past and by the current clerical regime. Nevertheless, they still had “faith in the international community’s ability to present a just and a viable solution to resolve this conflict peacefully.”

Sixteen years later, Abdian despairs of seeing any improvement in the position of his people. “I don’t see any way out currently,” he told Arab News, though he dreams of self-determination for the Ahwazi in a federalist Iran.

In the meantime, “as an Ahwazi Arab, you cannot even give your child an Arabic name. So, this nation, which owns the land that currently produces 80 percent of the oil, 65 percent of the gas and 35 percent of the water of Iran, lives in abject poverty.”