DUBAI: When a handful of pharmaceutical firms began the roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines in early 2021, many thought the worst of the pandemic was over. Indeed, the idea of a tangible weapon against the virus that had killed millions and devastated economies worldwide was temporarily empowering.

Within months, a selection of vaccines hit the market, with countries racing to secure enough doses for their populations in the hope of preventing further disruption. More than 9 billion doses later, with about half the global population “fully vaccinated,” it seemed as though the tide was finally turning against the virus and that normal life could soon resume.

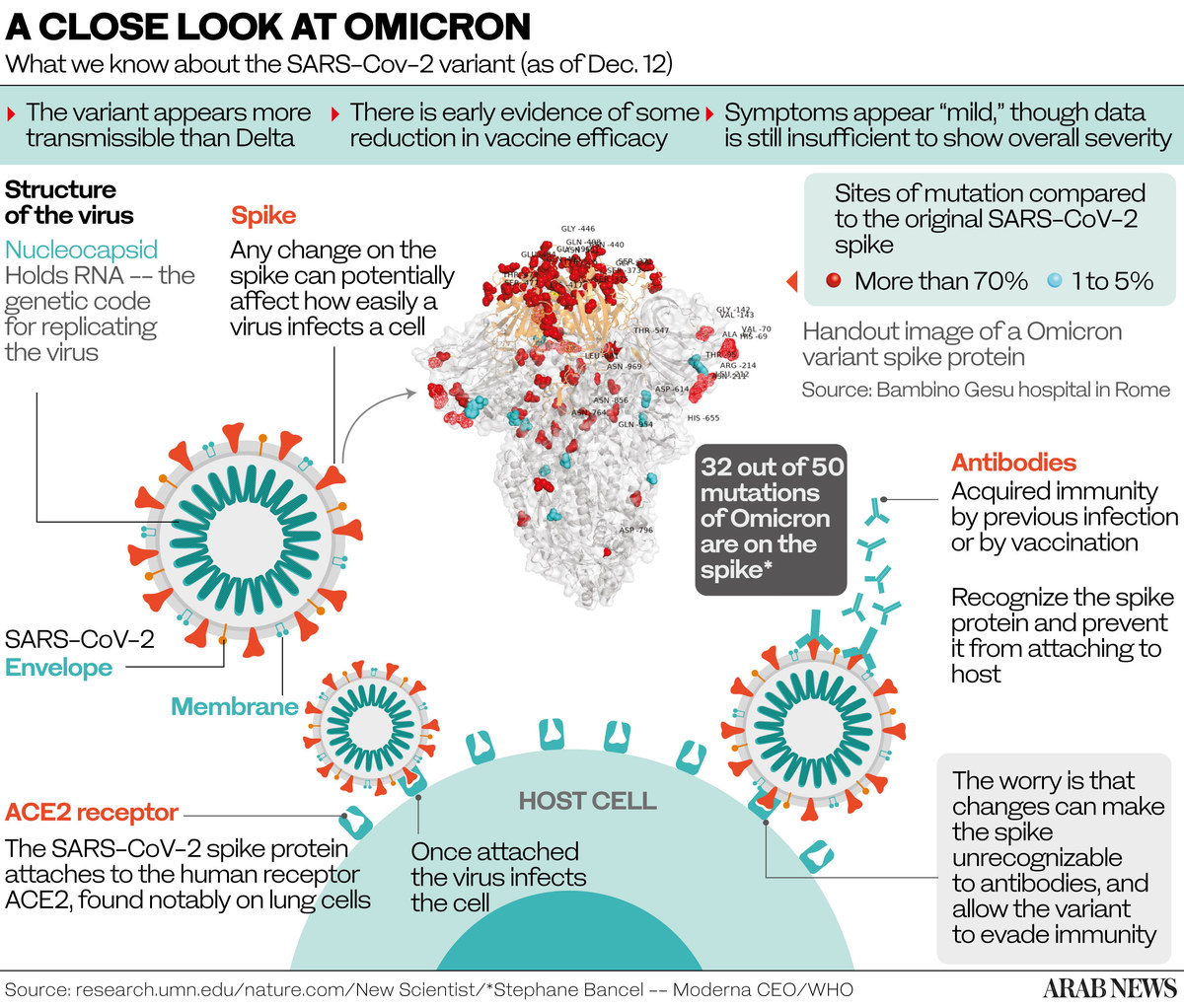

Sadly, such optimism would prove short-lived. Although the vaccine roll-out reduced the severity of COVID-19 symptoms, alleviating pressure on hospitals and saving many lives, scientists have struggled to contain mutations of the virus, including the latest highly transmissible omicron variant, which has broken through the vaccine shield.

This has forced pharmaceutical firms to return to the drawing board to consider variant-specific vaccines, an extended booster program to prolong immunity, or even “universal” vaccines that can tackle every variant of the virus. Such a pan-coronavirus vaccine could become publicly available in the not too distant future.

Emmanuel Kouvousis

“I believe a fourth (omicron specific) dose could become available in another six to nine months, as long as the omicron variant is dominant,” Emmanuel Kouvousis, a senior scientific adviser at Vesta Care, told Arab News. “However, if another more disruptive variant emerges, then we need to consider a scenario where we get a booster shot every three months.”

Kouvousis says a change in seasons could help delay the emergence of a new variant as the spread of the virus tends to slow in the spring and summer months. This could offer scientists a window of opportunity to get ahead of new variants.

“Many people ask if there will be a solution to this pandemic, and I say absolutely,” Kouvousis said. “There is huge hope that this pandemic will end, firstly because billions of people have been vaccinated and many others have been persuaded that the only way out of this is through vaccines, and secondly, because of a pan-COVID or ‘universal’ vaccine, which is currently in the testing phase.”

With billions of people already vaccinated, it is hoped that the COVID-19 pandemic will end. (AFP file photo)

Last year, the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases awarded $36.3 million to three academic institutions — Duke University, the University of Wisconsin, and Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital — to research and develop universal vaccines.

“We want a pan-coronavirus vaccine so that you have it on the shelf to respond to the next viral pandemic,” Anthony Fauci, the White House chief medical adviser, told NBC in January.

Separately, he told a Senate committee the development of a universal coronavirus vaccine could help the world tackle the next pandemic. “There’s a lot of investment, not only in improving the vaccines that we have for SARS-CoV-2, but a lot of work ... to develop the next generation of vaccines, particularly universal coronavirus vaccines,” he said at the hearing.

Among the scientists working on the vaccine are a team at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. Reporting promising results in animals, their version of the universal vaccine is known as the SARS-COV-2-Spike-Ferritin-Nanoparticle (SpFN) vaccine, currently in phase 1 of human trials.

So far, the three-dose vaccine has been tested with two jabs 28 days apart followed by a third shot six months later. Kayvon Modjarrad, co-inventor of SpFN, said in a press statement that the new vaccine uses a harmless portion of the COVID-19 virus to build up the body’s defenses.

This method follows the same used in developing universal flu vaccines, an approach that is different to that used in three of the most popular COVID-19 vaccines today.

COVID-19 has proved to be tougher than earlier thought, mutating into numerous variants as vaccine experts try to suppress it. (AFP file photo)

Vaccines produced by Pfizer and Moderna use messenger RNA (mRNA) to teach cells how to make a protein that will trigger an immune response inside the body, thereby building immunity. Meanwhile, others like the Johnson & Johnson vaccine use a harmless rhinovirus to train the immune system to respond to COVID-19.

Despite the huge progress made in vaccine production and distribution over the past year, the coronavirus, with its ever-growing family of variants, all named after letters of the Greek alphabet, continues to defy efforts to find the proverbial silver bullet.

Confidence among the fully vaccinated plummeted in the run-up to the winter holidays after the World Health Organization named omicron a variant of concern. It went on to infect a record number of people within a matter of days, pushing many countries to reimpose containment measures.

As COVID-19 continues to defy international efforts to put it under control, booster shots are being widely administered to maintain immunity. (AFP file photo)

Soon, millions of vaccinated people were informed that they would need a third or even a fourth dose to avoid becoming seriously ill. Even people who have already had the virus have been reinfected with the new variant.

Some countries, such as the UK, are working toward herd immunity, lifting almost all restrictions on travel and public spaces. However, Kouvousis is skeptical that herd immunity can be achieved through mass infection.

“It can only come about through vaccinations and having 90 percent of the world’s population fully vaccinated within a reasonable time span in order to avoid the emergence of new mutations,” he said.

In the meantime, booster shots are being widely administered in developed countries to maintain immunity. But even with a booster, experts say that the public should continue to follow hygiene and social distancing advice.

“The key after getting a booster shot is to wear the mask properly, which very few people do,” Dr. Gregory Poland, founder of the Mayo Clinic’s Vaccine Research Group, told Arab News. “The vaccines we have are predominantly disease-blocking and less so infection-blocking.”

Dr. Gregory Poland, founder of the Mayo Clinic’s Vaccine Research Group.

Part of the reason why developing nations are so far behind with the roll-out is the continuing monopolization of vaccine production and distribution by a few key players: AstraZeneca, BioNTech, Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, Novavax and Pfizer.

Just 10 percent of the African continent is currently immunized against the virus, leaving a gap for future dominant mutations to arise in these countries. Experts such as Poland want pharmaceutical firms to suspend their patents and share their vaccine formulas with smaller regional outfits, allowing them to produce shots closer to the point of need.

“This is a potentially important strategy,” he said. “Each sovereign nation gets to decide how to organize itself and protect its people. This includes national production facilities of those items critical to the well-being of the population or viable partnerships with other producers of the goods they need.”

To try and meet local demand and bridge the gap, several countries are working on their own generic vaccines and drugs to fight the virus. For instance, India’s first mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine “HGCO19” aims to offer protection against omicron specifically.

The vaccine, developed by Gennova Biopharmaceuticals Ltd., is set to begin human trials in the near future after early studies found the vaccine to be “safe, tolerable and immunogenic.” Similarly, Egypt’s first coronavirus vaccine, called “COVI-VAX,” is in the testing phase.

Meanwhile, the Philippines, which has one of Asia’s lowest vaccination rates, has authorized the use of a recombinant vaccine called “ReCOV” developed in China by Jiangsu Recbio Technology Co., as the country lacks the capacity to develop one of its own.

A Filipino resident receives a booster jab in Manila on Jan. 27, 2022 amidst rising COVID-19 infections driven by Omicron variant. (Maria Tan / AFP)

While still in its second phase of clinical trials, preliminary studies show that ReCOV has a sufficient neutralization effect on COVID-19 variants such as omicron and its earlier delta iteration.

Distribution has also been a major issue for hard-to-reach communities in the developing world. Shipping firms such as DHL have played a pivotal role in delivering vaccines, carting some 1.85 billion doses to 174 countries to date. But unless local authorities handle the cargo correctly on arrival, shots can be wasted.

“Vaccines are high value, extremely sensitive, and temperature-controlled items,” Fatima Ait Bendawad, head of DHL Global Humanitarian Logistics Competency Center in Dubai, told Arab News. “Any misstep in the logistics chain would result in potential loss of lives because the vulnerable can’t get to them on time.”

For Kouvousis, the problem is not entirely confined to the matter of production or distribution. In many cases, vaccination campaigns have proved slow or ineffective owing to the poor state of medical institutions in developing nations.

“The major players have the infrastructure to produce what is needed for the whole world,” Kouvousis said. “But some countries don’t have the infrastructure, the facilities or the education to use them effectively.”

After two years of ups and downs in the fight against the pandemic, the emergence of a pan-coronavirus vaccine would be a global game-changer. However, unless production and distribution are streamlined and enough people are administered shots in a short space of time, the opportunity to end the pandemic this year could yet be missed.