LONDON: Lebanon’s health system is in a precarious state following wave upon wave of political and economic crisis. As the country reels from medical supply shortages, COVID-19 case surges and an exodus of skilled medical professionals, the urgency of the sector’s need for outside help is no longer a matter of debate.

In most countries, it might seem reasonable to look to the government to implement reforms to rescue the health system from collapse. But in Lebanon, where it is arguably politics itself that is making the nation sick, the embattled state is unlikely to offer solutions.

A new study led by King’s College London and the American University of Beirut suggests Lebanon’s health system is in decline thanks in large part to the same disastrous political decisions and systemic problems that led to the country’s 2019 economic collapse.

The study, “How politics made a nation sick,” conducted by the Research for Health in Conflict–MENA project (R4HC-MENA), shows how a series of politically driven disasters has created a crisis state that is unprepared to deal with a deepening public-health emergency.

Dr. Adam Coutts, one of the R4HC-MENA project leads, describes the health situation in Lebanon as “a slow moving trainwreck, which sped up in the pre-pandemic period when the economy collapsed in 2019.”

Ever since the end of Lebanon’s civil war in 1990, sectarianism, clientelism and corruption have dominated political life and driven the country into successive bouts of unrest and instability.

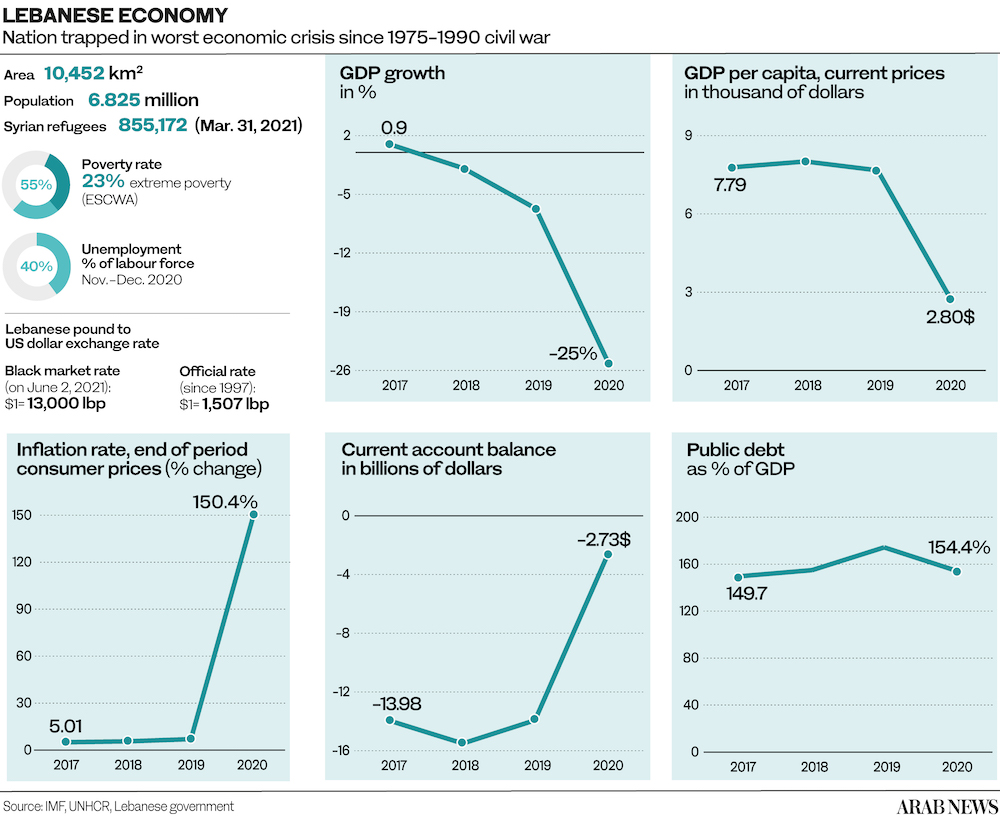

Corruption, hyperinflation and the 2019 banking sector collapse have plunged Lebanon into the worst economic crisis in its modern history. The arrival of millions of refugees from neighboring Syria has only compounded the strain on its creaking infrastructure.

About 19.5 percent of Lebanon’s population of 7 million are refugees from neighboring countries. Already living precariously in impoverished communities, few of them have the means or the connections to obtain vital medications at a time of scarcity.

Protesting pharmacists (above) hold signs saying “no gasoline = no ambulance,” denouncing the critical condition facing the country’s hospitals while grappling with dire fuel shortages. (AFP)

Meanwhile, the drastic devaluation of the currency has made health insurance unaffordable for many Lebanese.

“The social and economic situation in Lebanon right now is dire,” said Dr. Coutts. “We have been working on health, economic and social issues in Lebanon for ten years and have never seen it this bad.”

The steady depletion of foreign-currency reserves has made it difficult for Lebanese traders to import essential goods, including basic medicines, and has led banks to curtail credit lines — a disaster for a nation that depends so heavily on imports.

Furthermore, patients have been left struggling to access appointments and surgeries as medical staff flee the country in droves.

According to the R4HC-MENA study, about 400 doctors and 500 nurses out of the country’s 15,000 registered doctors and 16,800 registered nurses have emigrated since the onset of the crisis.

To make matters worse, Lebanon’s chronic electricity shortages have forced hospitals to rely on private generators to keep the lights on and their life-sustaining equipment functioning. But generators run on fuel, which is also perennially in short supply.

Despite the severity of the health care emergency, the Lebanese government has been unable to respond, lacking both the financial means and the willpower amid a multitude of overlapping crises.

“Health always seems to be viewed as the poor relation in development and early recovery compared to economic stabilization, education and security,” said Dr. Coutts. “The problem is if we continue to neglect health and health systems this leads to even bigger problems in the future.”

The COVID-19 pandemic arrived at the worst possible moment for Lebanon, further exposing the health system’s weakness and placing additional strain on the country’s battered economy.

A combination of images showing shuttered doors of pharmacies in Lebanon during a nationwide strike to protest against a severe shortage of medicine during 2021. (AFP/File Photo)

“As the COVID-19 pandemic shows, if you neglect health systems you cannot respond to health emergencies,” Dr. Coutts said. “Health is a top concern among people. It’s the street-level issue which affects everything in people’s day-to-day lives. Development needs to be about lives and livelihoods.”

While COVID-19 infections are currently falling in Lebanon, successive waves of the virus have exacted a devastating toll on Lebanon’s health system. In December 2020, for instance, about 200 doctors who lacked sufficient protective equipment to avoid infection were placed in quarantine.

The R4HC-MENA study found that successive peaks of the virus overwhelmed hospital capacity and resources, exacerbating shortage of staff, to say nothing of equipment such as ventilators and pharmaceuticals.

“Many private hospitals were reluctant to undertake COVID-19 care for fear of ‘losing’ income from more lucrative services, losing their physician and nursing staff, and lack of trust that they would actually be reimbursed by the government,” Dr. Fouad M. Fouad, R4HC-MENA project lead in Beirut, told Arab News.

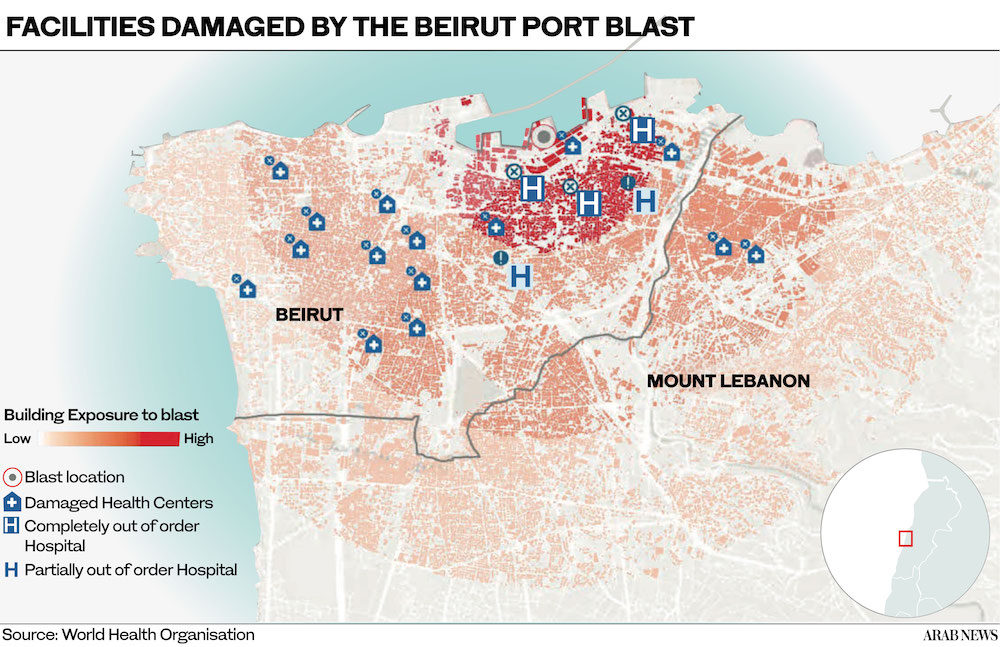

Just when it seemed things could not get any worse for Lebanon’s health sector, the Beirut port blast of Aug. 4, 2020 leveled a whole city district.

The damaged Saint George hospital (left) in Beirut more than a week after the port blast of Aug. 4, 2020. Some 43,000 Lebanese emigrated in the first 12 days after the explosion, including skilled workers such as medical staff. (AFP/File Photo)

More than 220 people were killed in the blast, about 7,000 injured, and some 300,000 left homeless. Within hours of the explosion, people began to pour into the city’s hospitals with all kinds of trauma, disfiguring burns and wounds caused by flying glass and masonry.

However, the blast also shattered the city’s health infrastructure. According to a WHO assessment, four hospitals were heavily affected and 20 primary care facilities, serving about 160,000 patients, were either damaged or destroyed.

“The explosion generated multiple health and rehabilitation needs among survivors,” Rasha Kaloti, research associate on the R4HC-MENA project, told Arab News.

“It also caused many patients to miss routine care for a variety of conditions, including critical care therapy such as cancer treatments, with many having to move to other hospitals, which led to delays and a lack of continuity of care.”

Doctors have warned that Lebanon is losing its best and brightest medical staff amid the crisis. (AFP/File Photo)

Meanwhile, the mental health impacts of the blast have only now started to become apparent, with survivors experiencing anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Embrace, a mental health awareness NGO in Lebanon, surveyed about 1,000 people aged 18 to 65-plus in the first 10 days after the blast. It found that 83 percent of respondents reported feeling sad almost every day, while 78 percent reported feeling very anxious and worried every day.

The blast has also accelerated the brain drain of skilled workers, including health staff. According to the R4HC-MENA study, 43,764 Lebanese emigrated in the first 12 days after the blast.

R4HC-MENA outlined several recommendations to help Lebanon salvage its health system. “The first thing that needs to happen is that clear political commitments are given to securing the health and wellbeing of the Lebanese and refugees,” said Dr. Fouad.

Despite the severity of the health care emergency, the Lebanese government has been unable to respond, lacking both the financial means and the willpower amid a multitude of overlapping crises. (AFP/File Photo)

“A new social contract needs to be created. Just signing a WHO declaration on Universal Health Care is not enough.”

Indeed, the causes of Lebanon’s health care collapse are largely political. For Dr. Coutts, a good first step might be to redefine the definition of “state failure” to incentivize the international aid community to pour resources into the health system.

“It is hard to see how Lebanon is not a failed state when the health system is on its last legs, half the population cannot afford to access the health system, three quarters of the population are on the World Bank poverty line, and a massive man-made explosion occurred in the middle of the capital city for which no one has been held accountable,” he said.

“If that is not state failure, then state failure needs redefining.”