NEW YORK: The UN is confronting the most serious challenge to the international world order that the organization rests upon since its founding 76 years ago.

The Russia-Ukraine war is threatening to upend the UN as we know it, potentially ushering in the end of multilateralism. There is an attempt by Ukraine and its allies at the UN to strip the Russian Federation of its Security Council seat, and some go as far as asking that the General Assembly expel Russia from the UN altogether.

These calls stunned diplomats and observers, and led to frantic discussions about the legality, as well as the likelihood of this happening and what it might mean for the future of the organization, with some describing the effort as opening a Pandora’s box. There is no telling where this will stop.

The first sign that the tectonic plates of the world order itself were being shaken came during the Security Council meeting the night the news of the Russian attack on Ukraine reached the Council while in session, chaired by none other than Russian Permanent Representative to the UN Vasily Nebenzya, the president of the Security Council for the month of February.

Sergiy Kyslytsya, Ukraine’s ambassador to the UN, questioned in the meeting the legitimacy of the Russian Federation’s membership of the UN, and said that the Russian ambassador should hand the Security Council presidency over to a “legitimate member.”

Kyslytsya addressed the secretary-general of the UN, Antonio Guterres, who was attending the meeting, and asked him to request the secretariat to “distribute among the members of the Security Council and the General Assembly a decision by the Security Council dated December 1991 that recommends that the Russian Federation can be a member of this organization, as well as a decision by the General Assembly dated December 1991 where the General Assembly welcomes the Russian Federation to this organization.”

He said “it would be a miracle if the secretariat is able to produce such decisions.” This is because they do not exist.

The Russian Federation inherited the Soviet Union’s UN seat without going through the proper process of applying and gaining the permanent seat on the Security Council, or membership in the General Assembly.

Experts are skeptical that the Ukrainian move will succeed for many reasons, but the foremost among them is the veto power of Russia, which could be joined by China in preventing expulsion.

This does not deter the Ukranians, though, from continuing their campaign to expel Russia from the UN and strip it of its permanent seat at the Security Council.

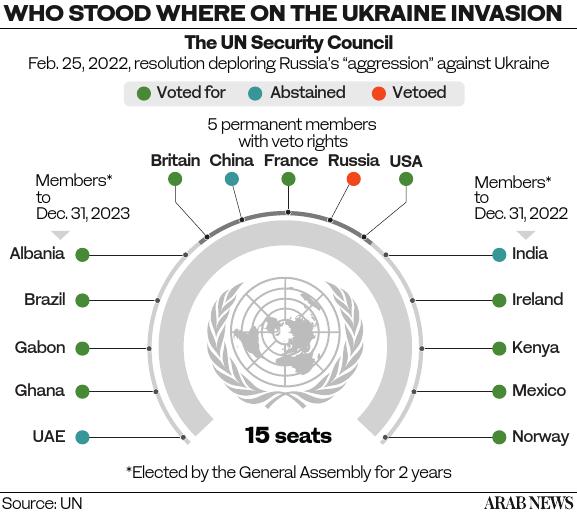

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky announced on Twitter that, in a call with Guterres, he talked about taking away Russia’s permanent seat after Russia used its veto to block the adoption of the Security Council resolution condemning its invasion of Ukraine.

The UN opened an emergency special session of the General Assembly to discuss Russia's invasion of Ukraine and observed a minute of silence for those killed in the conflict. (AFP)

Kyslytsya, in his tweets, addresses the Russian ambassador as the “gentleman in the Soviet seat.” The ambassador is using the fact that the Charter of the UN was not amended after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The charter, when naming the P5, the five permanent members of the Security Council, in Article 23, still lists the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics as a permanent member, not the Russian Federation.

There is also a procedure for admitting or expelling a member of the UN. These rules are spelled in articles 3, 4, 5 and 6 of the UN charter. Article 5 stipulates that a member of the UN “against which preventive or enforcement action has been taken by the Security Council may be suspended from the exercise of the rights and privileges of membership by the General Assembly upon the recommendation of the Security Council.”

Expelling a member also falls under Article 6, which opens the door for expelling a member that “persistently violates” the principles of the charter, by the General Assembly, but it also requires a recommendation from the Security Council.

South Africa was suspended from the General Assembly in 1974 over its apartheid policy, but with a Security Council recommendation.

Ukrainian Ambassador to the UN, Sergiy Kyslytsya (R), speaks with US Ambassador to the UN, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, before a Security Council emergency meeting, in New York on March 11. (AFP)

The representative of Tunisia then, in his capacity as the chairman of the African Group at the UN, requested a meeting of the Security Council to discuss South Africa and urged the council to invoke Article 6 of the charter and expel South Africa from the UN. The USSR representative supported the demand of South Africa’s expulsion from the UN as well.

The Russian veto in the Security Council makes it very difficult to expel it or suspend its membership in the General Assembly.

There is a precedent for using the veto to stop any action against a member involved in a matter that affects peace and security. It was exercised twice by the Soviet Union in its vote on the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, and during the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Incidentally, after Russia used its veto during the Security Council vote on the Ukraine resolution last month, Mona Juul, the Norwegian ambassador, called on Russia to abstain from voting because it is a party to the conflict.

She said: “A veto by the aggressor undermines the purpose of the Security Council,” and “in the spirit of the charter, Russia, as a party, should have abstained from voting on this resolution.”

Russia claims it is acting in self-defense under Chapter 51 of the Charter and so the rule does not apply to its “special military operation.”

It is astonishing that questioning the legitimacy of the Russian seat came 30 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, especially that no one challenged the transition from the USSR to the Russian Federation at the UN.

Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation to the United Nations, Ambassador Vasily Nebenzia speaks during a hybrid press briefing. (AFP)

On Dec. 21, 1991, the former Soviet Republics, 11 out of 12 of them, which formed the CIS (The Commonwealth of Independent States, which replaced the Soviet Union), supported Russia’s “continuance of the membership of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in the UN,” including the permanent seat in the Security Council, as well as in all the UN organizations.

Boris Yeltsin, then president of Russia, informed the US side on December 15, 1991, that Russia wanted to take over the Soviet seat at the Security Council. He sent a letter to the secretary-general of the UN declaring that Russia would continue its Soviet Union membership, supported by the CIS states.

By using the word “continuance,” Russia avoided going through the formal process of applying for the UN membership and getting the Security Council and the General Assembly to approve it through a vote. Ukraine now is saying that Russia should have done so.

It is worth recalling that the transition prompted at the time a legal debate about whether Russia was a “continuation” of the Soviet Union or a “successor.”

The continuation camp argued that Russia was the core of the Soviet Union and that, while the Soviet Union had ceased to exist, its core, Russia, was a continuation of the previous entity and therefore could inherit all its rights and obligations.

The successor camp, on the other hand, believed that when the Soviet Union ceased to exist, its seat at the Security Council no longer existed to be inherited by Russia. But few objected and Russia continued unchallenged — until today.

There are voices now calling for using the “Uniting for Peace” resolution, which allows emergency sessions of the General Assembly when the Security Council is blocked, to approve stripping Russia of its seat at the Security Council and even its UN membership.

This call found supporters in Washington, D.C., with a number of Republican members of Congress using Twitter to demand that “Russia be kicked off the UN Security Council.” One of these senators “plans to introduce a resolution in Congress to encourage the UN to remove Russia from the Security Council,” according to Fox News.

This Maxar satellite image taken and released on March 11, 2022 shows an overview of damaged buildings and burning fuel storage tanks at Antonov Airport in Hostomel. (AFP PHOTO / Satellite image ©2022 Maxar Technologies)

The Biden administration does not seem eager to take on this fight. When Linda Thomas-Greenfield, the US ambassador to the UN, was asked about it on CNN, she almost dismissed it and said: “Russia is a member of the Security Council. That is in the UN Charter.”

Experts and specialists in UN rules and procedures are highly skeptical “that you can strip Russia of its UN membership,” as Richard Gowan, the Crisis Group’s UN director, told Fox News. He said: “Russia could kill the process stone dead with its veto.”

The issue will also receive stiff resistance from the UN membership, including the P5, because it will set a precedent that no P5 member could be immune from the same fate in the future.

There is a consensus among diplomats at the UN that this process will not take off. Russia still enjoys support in the General Assembly, despite the fact that 141 members voted in favor of the resolution condemning its invasion of Ukraine.

Many countries voted for the resolution either because of political pressure or in support of the principles of the UN Charter. Ousting Russia from the Security Council or the General Assembly is seen as a political issue that will divide the General Assembly, and might even put the UN itself, and the international order, in danger.

It is doubtful that the developing world, no matter what the pressures are, will even entertain this possibility in the absence of any dramatic changes in the balance of power on the ground in this conflict.