DUBAI: They have become a sign of our times: Long queues of people in distress at border checkpoints, carrying the few belongings they could grab before hurriedly abandoning their homes and livelihoods. Hunger gnaws away at their dignity while their eyes plead for mercy, yet they must do exactly what they are ordered by impassive border guards tasked with maintaining order.

Nearly seven years after a record number of arrivals of refugees and migrants led to a crisis in the European Union, the spectacle of a mass flight of people out of Ukraine has brought the global refugee crisis to the fore. It has also prompted accusations of double standards and racial discrimination in Europe’s embrace of civilians displaced by war.

Since February 24, more than 4.1 million Ukrainians have fled to neighboring countries, producing the sixth-largest refugee outflow of the past 60-plus years, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of UN data.

These Ukrainians, taken in by Poland, Romania, Moldova, Hungary, Slovakia, Russia and Belarus, are part of a human tide made up of more than 10 million people, representing over a quarter of Ukraine’s pre-war population, who are thought to have fled their homes.

UN aid agencies are scrambling to find funds and resources to house, feed and treat wounded and traumatized Ukrainian refugees, all the while hoping a peace deal can be secured quickly to allow them to return home safely.

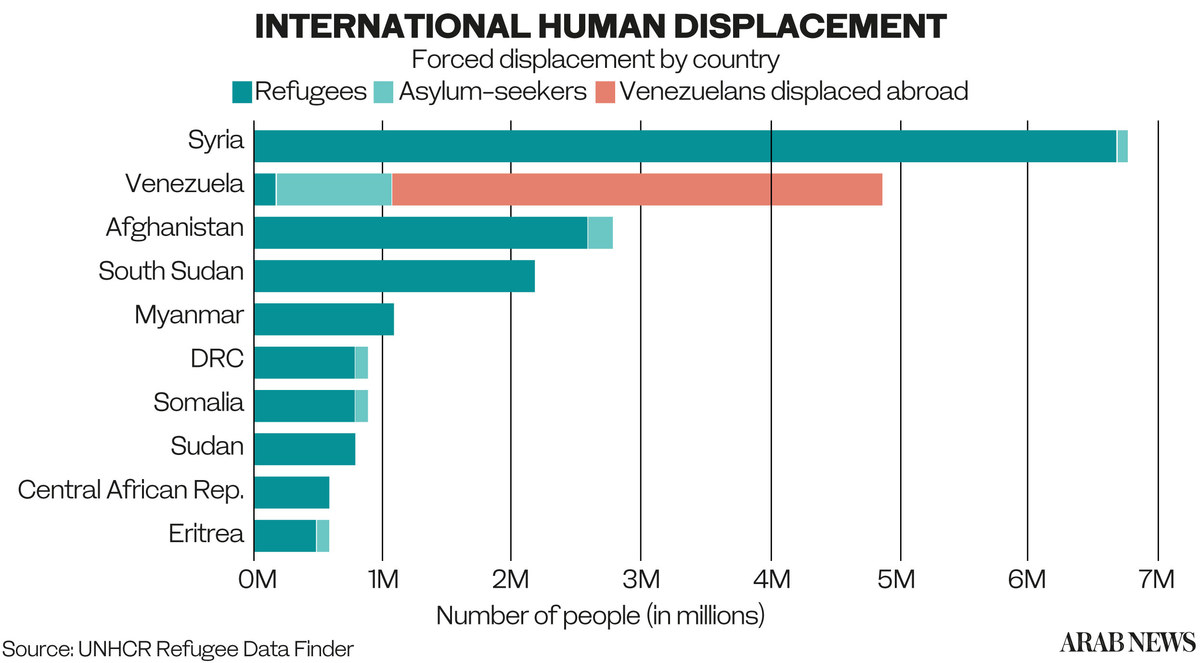

But even the biggest refugee crisis of modern times cannot obscure the mind-boggling scale of the problem on a global level. According to the UN, at least 84 million people, almost half of whom are children, are currently displaced worldwide.

If the war in Ukraine drags on without a clear conclusion, the civilians forced from their homes by the fighting may end up as a mere statistic, accounting for no more than a small fraction of the total number of war-affected people the world over who have nowhere to go, in many cases even decades later.

These victims of conflicts are denizens of refugee camps across the Middle East, Asia, Africa, South America and Southern Europe, unable to return home or move on to a new country. What were originally intended as temporary shelters became over time permanent settlements, absorbed by host communities.

Across the Middle East and Central Asia, there has been scant progress in returning or resettling the millions of people who have fled the spate of major conflicts over the past 20 years.

Poland has welcomed more than 2 million people from Ukraine since the outbreak of the conflict, when refugees braved freezing cold temperatures and long queues to make the journey westward. (AFP)

The US invasion of Iraq in 2003, which ousted dictator Saddam Hussein, sparked a deadly Sunni insurgency and a sectarian war in 2014 that contributed to the rise of Daesh. The resulting violence and insecurity forced millions of Iraqis — ethnic Arabs, Kurds and other minorities — from their homes.

More than 260,000 fled Iraq and 3 million more were internally displaced during this period. Many of those who remained inside the country settled in camps or informal settlements in urban areas of the Kurdistan Region of northern Iraq.

The UN refugee agency UNHCR estimates more than 4.1 million Iraqis, around 15 percent of the country’s post-war population, still need some form of protection or humanitarian assistance, years after Daesh’s territorial defeat in late 2017.

The conflict spilled over into neighboring Syria, where an uprising against the regime of Bashar Assad had already sparked an exodus of civilians into Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon, three countries where the bulk of them remain to this day.

Since 2011, more than half of Syria’s pre-war population of 22 million have faced forced displacement, many more than once. An estimated 6.7 million Syrians remain internally displaced.

A large number have sought shelter in Idlib, a volatile, rebel-held corner in the northwest that comes under routine regime and Russian bombardment.

At least 84 million people, almost half of whom are children, are currently displaced worldwide, according to the UN. (AFP)

Hajj Hassan, originally from Syria’s Homs region, was first displaced in 2012, then again in 2016. The 62-year-old has been in Idlib ever since. “We lost everything in 2012,” he told Arab News.

“Not a single building was left standing. I moved again and the bombardment followed. I now live in the world’s most miserable place. I am a refugee in my own country.”

Syrian children have borne the brunt of displacement, through exposure to violence, shock, trauma, hunger and harsh weather conditions. Many have been forced to grow up in exile, often separated from their families, where they have been subjected to violence, forced early marriage, recruitment by armed groups, exploitation and psychological distress.

Elsewhere in Asia, since the collapse of the internationally recognized government in Kabul in August last year, Afghanistan has been beset with humanitarian challenges, made worse by reductions in foreign aid, international trade and the nature of Taliban governance.

Afghans have been the victims of civil wars, insurgencies, natural disasters, poverty and food insecurity for the past 40 years, and today form one of the world’s largest refugee populations, with at least 2.5 million registered by the UN, most in neighboring Iran and Pakistan.

Since February 24, more than 4.1 million Ukrainians have fled to neighboring countries, producing the sixth-largest refugee outflow of the past 60-plus years. (AFP)

When the humanitarian crises in Yemen, Myanmar and North African countries are added to the mix, the refugee numbers seem too large for a war-weary world and an overstretched NGO community to handle.

Meanwhile, in the Middle East, aid agencies have been struggling to secure donor funding to support projects in Yemen, Syria and Lebanon. “Compassion fatigue” is threatening the viability of health and education programs in all three countries, senior aid workers say.

“Now, with Ukraine, there is going to be even less focus on Yemen than before. It may well be time to do something else,” one Middle East-based aid worker told Arab news. “I can’t deal with the crushing blow that would be walking away when the money runs out, so I may as well exit first.”

One thing common to the Ukraine war and recent Middle East conflicts is the major role played by neighboring countries in the humanitarian effort.

Just like the countries bordering Syria, which took in millions of refugees over the past decade, Eastern European nations that have accepted that displaced Ukrainians will likely need outside help to deal with the increased population pressure, especially if the invasion turns into a long, grinding war.

Lebanon currently hosts about 850,000 of the Syrians turned into refugees by the civil war, Jordan another 600,000 and Turkey more than 3 million. But weighed down by their own socioeconomic problems and fiscal difficulties, these countries have shown an increasing reluctance to shoulder the burden while attempting to push some refugees back to Syria.

Migrants wait to be rescued by members of Proactiva Open Arms NGO in the Mediterranean Sea, some 12 nautical miles north of Libya. (AFP)

Many of those who returned to their homes in the war-torn country found themselves rapidly enlisted into the national army or shaken down by mafia-style groups for protection.

While the influx of Ukrainians has elicited an outpouring of generosity from European governments, the continent’s unified welcome is in marked contrast to the lukewarm reception that the Syrian refugees received, to say nothing of the outright hostility to migrants who tried to cross the Belarus-Poland border late last year.

Indeed, it seems hard to believe that just a matter of months ago, Poland began work on a $380 million wall along its border with Belarus to block thousands of non-European refugees seeking asylum in the EU.

“The situation of non-Ukrainian refugees at the borders, especially right now, has been horrible. It’s been appalling to watch,” Nadine Kheshen, a Lebanon-based human rights lawyer, told Arab News.

“On the one hand, it’s beautiful to see Ukrainians being welcomed with open arms. On the other, it’s heartbreaking to see how Syrian, Afghan, Kurdish, Iraqi and other refugees are being treated on the Polish border.”

Kheshen’s opinion is echoed by Nadim Houry, executive director of the Paris-based Arab Reform Initiative think tank. “There is no doubt some sort of double standard in the way refugees are being treated,” he told Arab News. “I would say, particularly vis-a-vis Afghan refugees in Europe, this must be condemned. People fleeing violence should be welcomed.”

Rohingya refugee children play in Kutupalong refugee camp in Ukhia, on March 27. (AFP)

Although the needs of refugees are the same no matter where they come from, it does seem that the kind of conflict they are fleeing could well determine how long they are displaced, or whether they can return at all.

“There is a major difference between Ukraine and Syria, for example,” said Houry. “In the case of Ukraine, people are fleeing an external aggressor. The moment the external aggressor stops, people will feel safe going back. However, in Syria, people were fleeing the Syrian regime mostly.

“The same happened between Israel and Lebanon in 2006. You had massive displacement, but once the Israelis stopped, the Lebanese went back to their towns.”

Although Eastern and Central European countries have been quick to welcome the millions of Ukrainians arriving on their soil, there are concerns that the new arrivals could ultimately find themselves consigned to a life as permanent refugees. Many might eventually outstay their welcome.

“We are now seeing high levels of support and welcoming by neighboring countries and high levels of solidarity,” Houry told Arab News. “However, some countries, such as Moldova and Poland, will require support so as not to be strained.

“People tend to forget the beginning of the conflict in Syria. Syrian refugees were generally welcomed. But then it changed as the conflict raged on.”

So far, Europe’s show of solidarity with people fleeing the war in Ukraine has been impressive. But given that the invasion is entering just its fifth week, it may be early days yet.