DUBAI: The World Economic Forum’s Chief Economists Outlook report has warned of potentially dire human consequences that could result from the fragmentation of the global economy, exacerbated by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

In their latest quarterly report, published on Monday, day two of the WEF annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland, experts forecast higher rates of inflation in the US, Europe and Latin America, with a resultant decline in real wages in both high-income and low-income countries.

The regions that appear particularly vulnerable to a lower rate of economic activity include the Middle East and North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, which have already experienced worsening levels of food insecurity in recent years.

As supply chains enter a third year of disruption, governments and businesses are rethinking their approach to exposure, self-sufficiency and security. As a result, experts warn that firms are realigning their supply chains along geopolitical fault lines, creating a new “economic iron curtain.”

Economists fear these trends could set global development back decades.

“We are at the cusp of a vicious cycle that could impact societies for years,” Saadia Zahidi, the WEF’s managing director, said in a statement issued on Monday.

“The pandemic and war in Ukraine have fragmented the global economy and created far-reaching consequences that risk wiping out the gains of the last 30 years.

Saadia Zahidi, WEF managing director, speaking during the panel discussion on Monday. (Supplied)

“Leaders face difficult choices and trade-offs domestically when it comes to debt, inflation and investment. Yet business and government leaders must also recognize the absolute necessity of global cooperation to prevent economic misery and hunger for millions around the world.”

The most visible effect of this disruption has been the rising price of food. The war in Ukraine is expected to increase wheat prices by 40 percent this year, while the price of vegetable oils, cereals and meats continue to skyrocket.

The process of “deglobalization,” a term coined by the Chief Economists Outlook report in 2021 to describe the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, has been expedited by the economic and geopolitical fallout from the invasion of Ukraine.

The country is one of the world’s biggest exporters of grain and vegetable oils and the blockade of its Black Sea ports has disrupted the global supply of these commodities. In addition, Ukrainian farmers displaced by the conflict have been unable to tend this year’s crops, foreshadowing further shortages.

During a panel discussion at the Davos meeting, David Beasley, executive director of the World Food Program, said that about “49 million people are knocking on famine’s door in 43 countries,” including Yemen, Lebanon, Egypt, Mali, Burkina Faso, Congo, Guatemala and El Salvador.

“This is going to be hell on earth,” Beasley said on the opening day of the WEF event. “Because of this crisis, we are taking food from the hungry to give to the starving.”

It is not only rising food prices that concern economists. The World Bank expects energy prices to increase by 50 percent in 2022, before easing in 2023-24. Many fear that government efforts to mitigate the threat of energy insecurity will prioritize carbon-intensive sources rather than green renewables, setting back climate action.

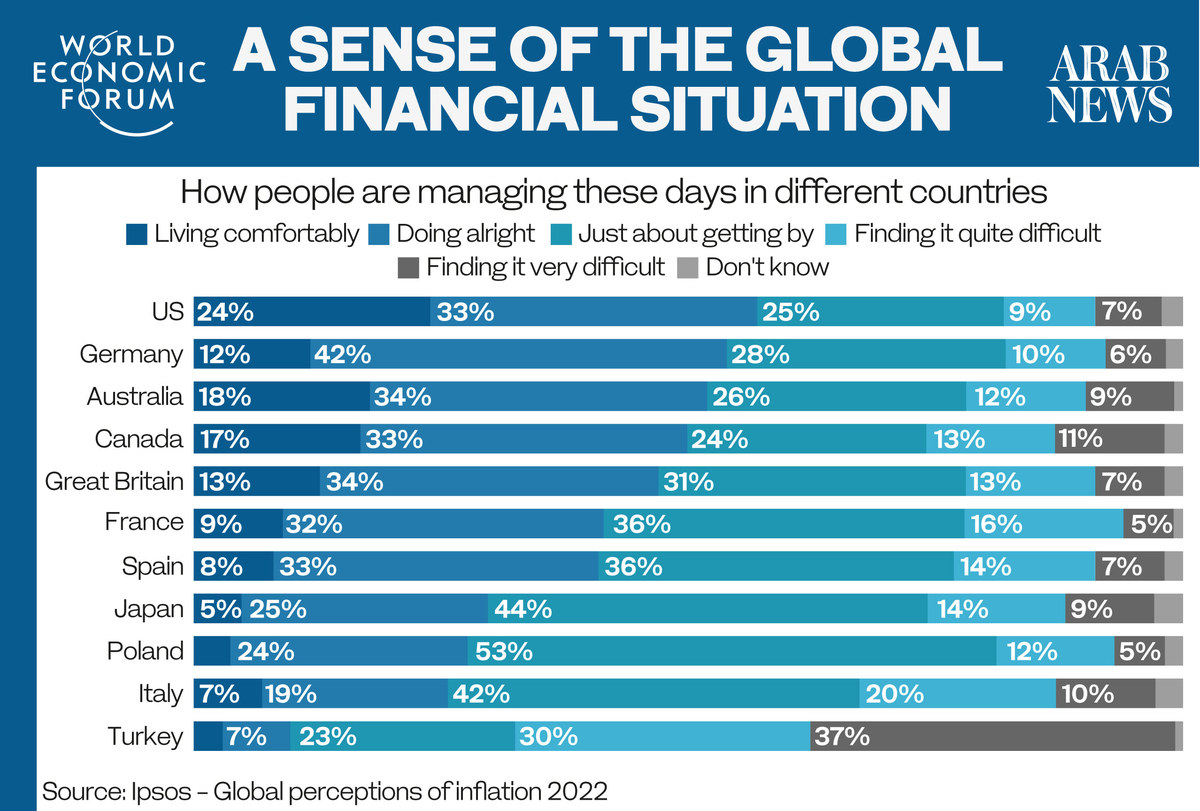

In many advanced economies, the rising cost of living is already having a detrimental effect on quality of life.

Speaking during a visit to Tokyo on Monday, US President Joe Biden acknowledged the squeeze many Americans are feeling as a result of high inflation and supply-chain shortages but said a recession is not inevitable.

“Our GDP is going to grow faster than China’s for the first time in 40 years,” he said. “Now, does that mean we don’t have problems? We do. We have problems that the rest of the world has, but less consequential than the rest of the world has because of our internal growth and strength.”

Biden’s rejection of an imminent economic slump in the wake of financial market jitters about “stagflation,” which means persistent high inflation combined with high unemployment and stagnant demand in an economy, found backing from another of the speakers at the Davos gathering, Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the International Monetary Fund.

Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, participating in a panel discussion of the WEF on Monday. (Screengrab from WEF video)

However, she admitted that the IMF expects weak growth in comparison with last year, when the world was emerging from the worst of the pandemic, and added that there is now a risk of further declines because of the war in Ukraine and the resulting fragmentation.

“The costs of further disintegration would be enormous across countries,” Georgieva said in a blog post ahead of the WEF meeting, highlighting the potential for new waves of cross-border migration.

“And people at every income level would be hurt — from highly paid professionals and middle-income factory workers who export, to low-paid workers who depend on food imports to survive.

“More people will embark on perilous journeys to seek opportunity elsewhere.”