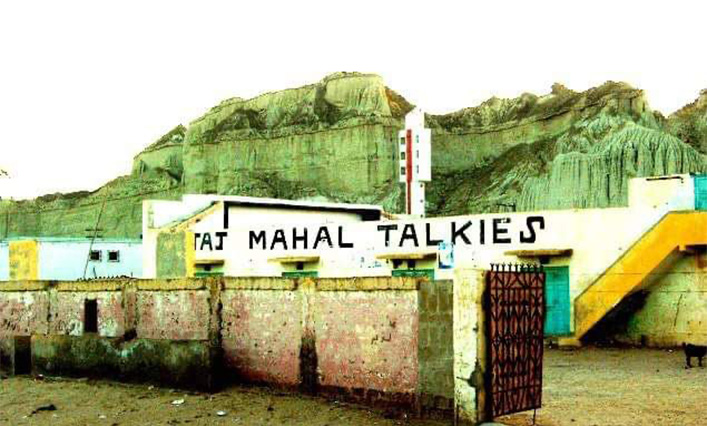

GWADAR: When he drives his rickshaw past the yellow building of Taj Mahal Talkies, Ali Muhammad can never resist to stop and recall how he used to paste on its walls the posters of Pakistani blockbusters.

Opened in 1973, the cinema was one of the only two in Gwadar — a fishing town of 50,000 people in Balochistan, an impoverished province of southwestern Pakistan, which is now a key destination for Chinese infrastructure investment projects.

The theater served as a main source of entertainment in the city for over three decades until it closed in 2006. The other one, Balochistan Talkies, shuttered even earlier.

Taj Mahal Talkies witnessed the best years of Pakistani cinematography, its “golden era,” attracting hundreds of people to its screenings of hits such as “Nadaan” (“Innocent”), a 1973 drama featuring legends Nadeem and Nisho, “Jadoo” (“Magic,” 1974), featuring legendary actors Sudhir and Mumtaz, “Parastish” (“Worship,” 1977), a drama with Mumtaz, Nadeem, and Deeba, and hundreds more.

In this photo from the 1990s, Ali Muhammad, a former assistant at Taj Mahal Talkies in Gwadar, Pakistan, poses with a movie poster. (Photo courtesy: Ali Muhammad)

Muhammad most vividly remembers “Shadi Magar Aadhi,” a 1984 hit whose poster was the first he had pasted during his Taj Mahal career.

The film is still most special to him, and on he often plays its soundtrack to remember the times when the cinema was full of people.

Now not even chairs are left, and only a huge white screen remains on a blistered wall of the ruined building.

A white cinema screen remains on a blistered wall of the ruined building of Taj Mahal Talkies in the southwestern port city of Gwadar, Pakistan, on May 20, 2022. (AN Photo)

“But when I enter here, I go back to the golden days when this space would be full of film enthusiasts,” Muhammad told Arab News. “I continued to paste posters till it was closed.”

When Taj Mahal was shut, he started working as a fisherman and recently became an auto-rickshaw driver.

Ali Muhammad, a former assistant at the Taj Mahal Talkies, drives his rickshaw in Gwadar, Pakistan, on May 20, 2022. (AN Photo)

“When the cinema was shut down, I was very upset,” he said. “Even today, I’m very sad.”

The posters he had pasted onto the walls of the theater building and in the city center would tell its residents which film would screen that day.

Saleh Muhammad Sajid, who joined Taj Mahal Talkies as projectionist in 1976, said women sent their children to Gwadar’s main square, Mullah Fazal Chowk, to check the posters and see the repertoire.

He remembered how even 1,000 people would come to the movies at some evening screenings.

An undated photo of now defunct Taj Mahal Talkies cinema in Gwadar, Pakistan. (Photo courtesy: Nasir Rahim)

When the 1968 classic “Shahi Mahal” with Mohammad Ali and Firdous was once scheduled for screening, Sajid said, people swarmed the cinema in such huge numbers that one of its walls collapsed.

“The enthusiasm had no boundaries. When the hero would hit the villain or deliver a punch, people would toss a coin toward the screen, in a show of appreciation,” he told Arab News.

Gwadar residents would endlessly talk about a movie from the moment they woke up the next day after screening.

Ali Muhammad plays a film on his mobile phone against a cinema screen at dilapidated Taj Mahal Talkies, in Gwadar, Pakistan, on May 20, 2022. (AN Photo)

“‘Mohammad Ali was hit,’ one man would remark. The other would reply ‘no, Sudhir had run away,’ while another would interrupt ‘no, actually it was Sultan Rahi,’ and the discussion would go on for the day.”

The good streak would last until the mid-1990s, when Pakistan’s film industry started to collapse and people generally began to turn away from cinema.

There were very few Pakistani productions to play and although in neighboring India cinema was booming, Bollywood films could not make it to Pakistani screens — ban on Indian movies, imposed after the 1965 India-Pakistan war, remained in place.

“Had Indian films been allowed, Taj Mahal Talkies would have survived a few years more. Pakistani content could not grab the audience,” he said.

“When I see this building, my heart cries.”